Vol. 8, n. 2, ottobre 2022

LA RICERCA

Riorganizzare online un master universitario sui temi del colore, della luce e dello spazio

Saara Pyykkö1

Sommario

Il Covid-19 ha costretto le università a organizzare molti corsi di studio esclusivamente online. Questo articolo descrive il caso di un master universitario tenuto presso la Aalto University sui temi dello spazio, colore e luce, basato sul learning by doing. Lo scopo del presente contributo è analizzare le soluzioni pedagogiche utilizzate nei corsi tenuti a distanza. La ricerca sulla materia si è svolta prevedendo: un case study sulla pratica didattica; la documentazione del corso e del lavoro degli studenti; un questionario per gli studenti e note personali. Tre principi pedagogici riassumono i risultati: 1) nuove pratiche e regole dell’ambiente educativo via web; 2) la definizione di appropriati metodi e strumenti pedagogici per coinvolgere le persone durante il corso; 3) metodi per costruire l’esperienza del colore, della luce e dello spazio a distanza. Tutte le lezioni, i compiti e le escursioni virtuali sono stati adattati al web.

Parole chiave

Architettura, Educazione, Didattica online, Colore, Spazio, Luce.

THE RESEARCH

Teaching online the experience-based course «Colour-Light-Space»

Saara Pyykkö2

Abstract

Covid-19 forced university studies to the web. This paper describes the case study of an experience-based MA-level course at Aalto University about colour-light-space. The purpose is to evaluate and study the pedagogical methods used in the web-based educational environment. The research methods are: practice-based case study, documentation of the course and students work, a questionnaire for the students, and personal notes. Three pedagogical principles summarize the results: 1) new practices and rules of the web-based educational environment; 2) pedagogical methods for connecting people during the course; 3) methods for building the experience of colour, light and space for the web. All lectures, assignments and virtual excursions were adapted to the web.

Keywords

Architecture, Education, Web-based education, Colour, Light, Space.

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic changed university teaching in March 2020. When the lockdown started, the teachers converted their courses for the web during one weekend, mostly with limited skills and not much pedagogical knowledge for virtual teaching. «Education is the largest field of experience research. Many disciplines publish educational research on learning through experience, such as experiential learning» (Roto et al., 2021). Further research will explain the experiences of web-based teaching, learning and building the experience on the online education. One of the first documented examples on a university course on colour and light (Gabriele et al., 2020) concentrated mainly the practical challenges of turning a teaching to web-based, an online classroom and on practical tools in Webex software.

This case-study deals with an MA level university course at Aalto University, Finland. The course started in January 2021 and ended in May 2021. The previous course «Colour-Light-Space» during 2017-18 (4 ECTS) is documented (Arnkil and Pyykkö, 2018). The writer has been responsible for the course (enlarged into 6 ECTS) since 2019, including 64 hours contact teaching and 98 hours of students’ independent work. The aim is a deep experience-based understanding of the possibilities and the role of the colour and the lighting in the built environment. The 20 participants in 2021 studied architecture (9), interior architecture (3), landscape architecture (3), textile design (1) or visual culture (4).

The article concentrates on the documentation and evaluation of the course. The main pedagogical challenge of the course and the research question is: How to convert the experience-based and learning-by-doing-based course about the colour, light and space for the web? How to build experience, perception, discussions and interaction with students, and how to teach architectural colour design? The research methods are: practice-based case study, documentation of the course and student work, a questionnaire for the students, and personal notes.

Lectures and Assignments 1A-F, 2ABC, 3, 4AB

The course includes lectures, excursions and four types of assignments. The lectures deal with lighting (Roope Siiroinen), colour systems and colour models (Saara Pyykkö), colour design in the urban design context (Saara Pyykkö), in interior architecture (Päivi Meuronen), and in landscape architecture and art (Kaisa Berry). Unfortunately, all excursions such as those to iGuzzini and Tikkurila Oyj, as well as historical architecture such as the National Library of Finland and The Ateneum Art Museum (Kati Winterhalter) had to be organized only as webinars.

The four types of assignments are:

- 1A-F are short tasks about colour mixing with the watercolours, analyzing colours, practicing the NCS Colour system, using the PERCIFAL method, and the Colour walk .

- 2ABC includes three reading seminars. The students prepared one presentation during the course and acted as an opponent in other two reading seminars. 2A dealt with perception (Fridell Anter e Svedmyr, 2004) and architectural atmosphere (Böhme, 2017a; Pallasmaa, 2016; Tanizaki, 1997; Zumthor, 2010), and gave conceptual tools for the assignments 3. 2B gave practical tools for colour design strategies and colour designing (Delcampo-Carda et al., 2019; McLachlan, 2012; McLachlan et al., 2015; Porter e Mikellides, 2009; Serra Lluch, 2019; Smedal, 2001) for the last assignments 4A and 4B. 2C opened the meaning of colour in the work of architects, artist and designers, (De Heer, 2009), and presented the phenomenon synesthesia (Arnkil, 2003, 2021; Böhme, 2017b). The assigned literature consisted of books, scientific articles, and other writings. 2B and 2C included names without related literature: James Turrell and Olafur Eliasson, Roberto Burle Marx, Luis Barragan, Bruno Taut, Matthias Sauerbruch, Luisa Hutton and Le Corbusier, where the students used books and web-based visual material as sources. After the reading seminars, the students shared their PowerPoint-presentations, and which gave them condensed knowledge from several disciplines.

- Task 3 was the Analysis of the architectural atmosphere of a street or a block (figure 1 and 2). The main idea was to gain understanding about the atmosphere of the site, identifying the main aspects and how those aspects change. The name of the course is «Colour-Light-Space», so they were the main aspects to study. However, other factors such as ageing of facade, its wetness, the illumination and the weather, involved in their perception and experience. The students needed to visit their blocks at least three times in different illuminations and weather conditions. The buildings were of different architectural styles, building materials and colour scales.

- The last task, 4AB, summed up the earlier tasks, and the students applied their broadened understanding to a real on-going architectural colour design project including an Analysis of the site (4A; figure 3 and 4) and a Sketch of the colour design (4B; figure 5 and 6). The case was a new block with three buildings. The architect of this case study, Professor Pentti Kareoja from ARK-house architects Ltd, played a double role during the course. He was an architect of the project, needing a new colour design, and he was also a visiting critic in the reviews of the analysis of the site (4A) and the final sketch of the colour design (4B).

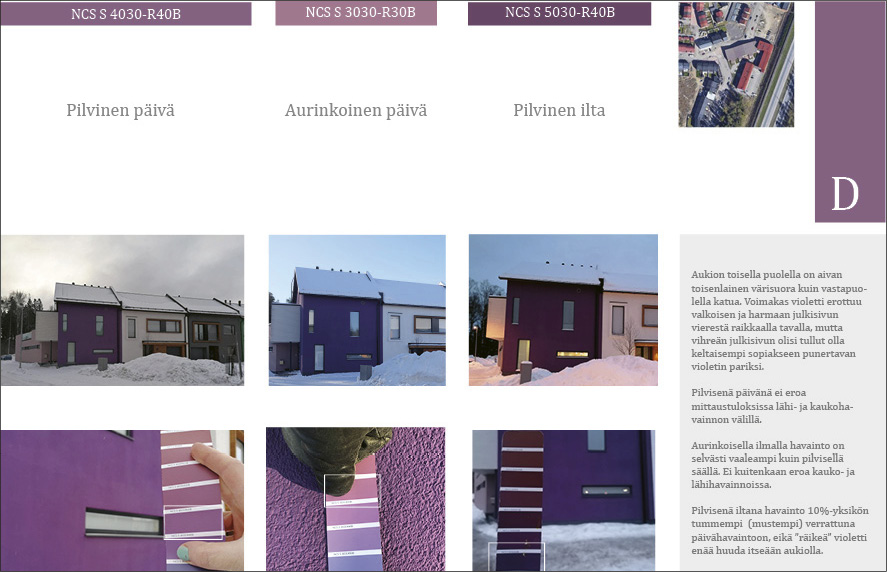

Figure 1

Assignment 3, Analysis of the architectural atmosphere. The students learned to use the NCS colour system as a tool of architectural colour design. One of the main highlights was to understand how the colours differ in cloudy daylight, sunny daylight, and cloudy evening (©Kirsi-Maria Raunio, MA student of Visual Cultures and Assi Lindholm, MA student of architecture).

Figure 2

Assignment 3, Analysis of the architectural atmosphere. A positive consequence of realising the course across the web was that one of the students started the course from Copenhagen and three other students took the course from other cities in Finland (©Janina Hedström, MA student of architecture).

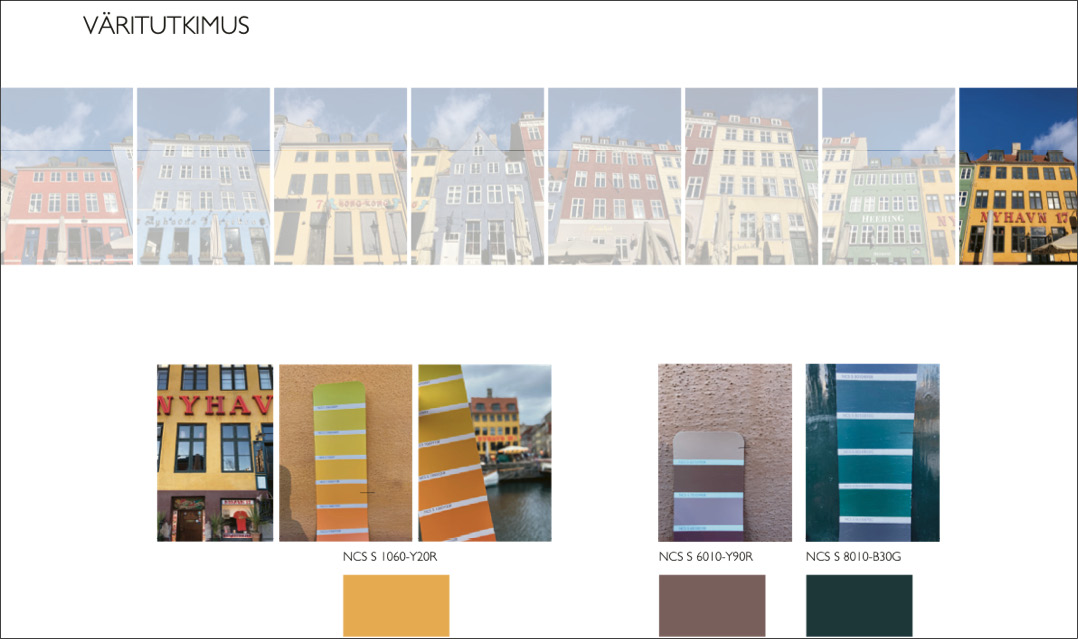

Figure 3

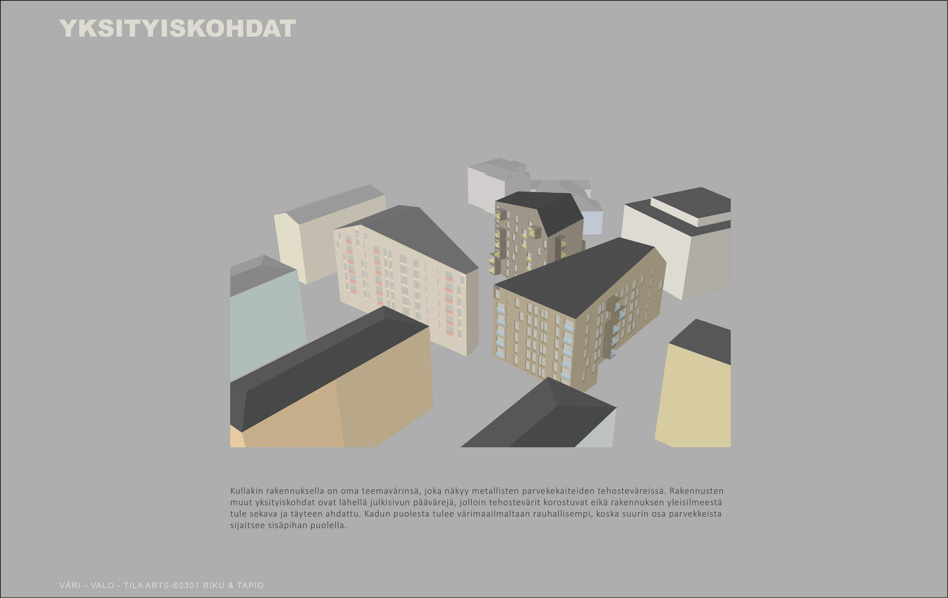

Assignment 4A, Analyses of the site. The students applied the new understanding from the task 3 to the real architectural project. The students used 20 hours for the analysis of the environment of the three new buildings (©Riku Kuukka, MA student of landscape architecture and Tapio Tuomi, MA student of architecture).

Figure 4

Assignment 4A, Analyses of the site (©Julia Lehto, MA student of textile design and Assi Lindholm, MA student of architecture).

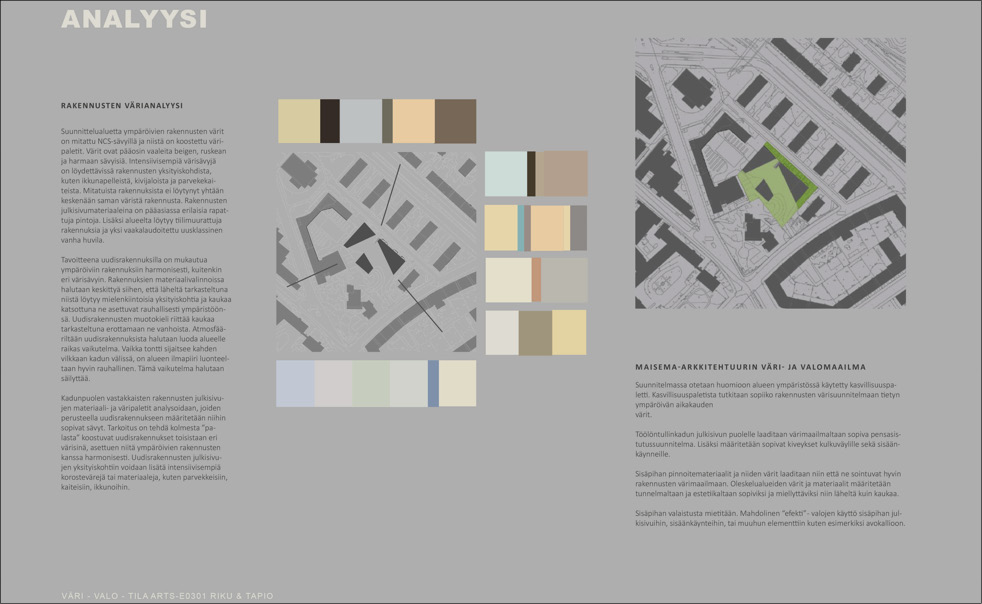

Figure 5

4B, The sketch for the colour design. The students used 20 hours for the last task, and they designed with several design methods (©Riku Kuukka, MA student of landscape architecture and Tapio Tuomi, MA student of architecture).

Figure 6

4B, The sketch for the colour design. According to the feedback, many students said that they rediscovered doing with hands, and they will use not only the computer, but drawing, watercolours and painting as a design method in the future (©Julia Lehto, MA student of textile design and Assi Lindholm, MA student of architecture).

Three Pedagogical principles for making a course Web-based

My participation in 7 Experiences, Aalto Experience Summit in September 2020 revolutionised my approach to web-based communication. The organizer provided the participants step-by-step instructions on how to make the atmosphere of the meetings more focused, e.g., by organizing the physical working environment and avoiding multi-tasking. The new participation guidelines were based on state-of-the-art scientific knowledge on so-called Zoom fatigue and how to prevent it (e.g., Bailenson, 2021). My knowledge grew during the course with the interaction of the students and their feedback as a hermeneutic circle. The analysis of the pedagogical interventions used during the course and in the different type of assignments can be summarized as the following three pedagogical principles:

- New practice and rules of web-based educational environment. In the first meeting, I presented the rules of the course, and explained the scientific reasons behind it. The students used the sketchbook for their personal notes, and they took screenshots from the presentations if needed. To avoid multitasking, no «chat» was used. To avoid virtual meeting fatigue, (e.g., Aargaard, 2022; Epstein, 2020), we had after 45 minutes at least a small break, and after 90 minutes a longer break. During the breaks, I encouraged the students to look out from the window, to take a small nap and to avoid the social media. The course materials were available in MyCourses (the digital workspace used by the University). Several pieces of software were used during the course: Zoom was the main educational environment. The optimal time of breakout sessions varied between 15 to 30 minutes. Flinga was used in the virtual Colour Walk and for collecting the results and data from the breakout room sessions. The students used PowerPoint in their presentations and some of them SketchUp, Miro, Photoshop and ArchiCAD. One of the more innovative ideas was to use Google map for virtual traveling. One of the students used it to present Bruno Taut and his colour design projects in Berlin by traveling virtually to see the current colours of Taut-designed neighbourhoods. The critique meetings needed an exact schedule and instructions. The students presented their work in PDF documents and trained a 6-minute presentation beforehand. Then the visiting critic commented on the project, and to the end, I commented the learning process and its result. The students opened their learning process via their highlight moments of the process. Total time of critique session was for one student 12 minutes and for a pair work 15 minutes. The critique session on Zoom-platform is cognitively intensive to the brain, that the final critic session was divided into 2 hours meetings with one break.

- Connecting people. The Web connects people, but the second principle signifies the methods by which the connection, interaction and grouping between the students were pedagogically built. In the first meeting, the students presented themselves via pictures, and they told their personal motivation and aims for this course. In a virtual university course, the grouping at the beginning of the course needs attention. By this classic grouping method with the pictures, now sharing the pictures in Zoom, the students become visible as a person. They find easily the «perfect match» to work with. The social aspects of student-to-student interaction and their well-being were important. During lockdown, the four hours Zoom session could be the only social contact of the day. Students learned from each other, because all small groups were organized with students from different backgrounds. The teacher was not allowed to demand students to keep their camera on, but some voluntary faces helped the teacher to have a feeling of interaction. The best size of «breakout rooms» was a group with 4-5 participants. In a group of 6-7, one student had the role of «moderator» and another was a «secretary». The role of moderator was to activate silent students and to curb talkative persons. The secretary collected the answers to the question or the results of the discussion at hand. During the course, every person served in both roles.

- Building the experience. Building the experience refers to a single student’s experience and the shared experience of the group, and how the experience is built in assignments and lectures. The visitors were asked to build their presentations from the perspective of experience. For example, the lectures described the space and the place, not only through visual aspects, but also through other senses, such as the smell of the sea, the sound of the rushes in the wind, or the wetness of the walls. Tasks 1B (My water colour palette) and 1C (Four possible mixtures of ten basic colours), sensitized the students to the colour. Task 3, Analysis of the architectural atmosphere, was an important start to the main analysis and the design assignment. The understanding of experience and interaction of colour, light and space in human perspective grew through personal perceptions and experiences on the site, and from sharing those perceptions in the mid-critic sessions and discussions with the main group or in breakout rooms. Tanizaki’s In praise of Shadows and Pallasmaa’s The eyes of the skin were given as reading to increase awareness of all the senses. The Colour Walk method (Pyykkö, 2016) was developed to understand the colours of neighbourhoods and the influence of the detailed plan and design guidelines on them. However, I have used it as a learning method, too. Then the main aim is the walk, students’ perception, experience and discussion with the students, not the concepts of which they discuss. In 2020 the Colour Walk was realized in two parts. During the lockdown, only the students who were able to walk or drive to the area, did it. They walked the route, took photos, and made notes. After that, on the next Zoom-meeting, we «walked virtually» in Flinga software along the same route and discussed their perceptions, notes and experiences. The lack of the virtual Colour Walk was the personal sensorial experience of the atmosphere of the place. However, the virtual Colour Walk opened the experience of the pedestrian and deepened the understanding for the meaning of views, distances, spaces, volumes of architecture and material of the facades.

Feedback from the students

After the course, 8 out of the 18 students answered the questionnaire, and a few students delivered feedback by e-mail. All eight students gave the course the highest score (5/5) in their evaluation. 7 out of the 8 students gave 5/5 and 1 student gave 4/5 for the organization of the course. «The best organized course during the Corona!». I asked what five books/articles/professionals of the reading seminar supported the best their studies. 63% answered Fridell Anter and Svedmyr, 38% the presentations about Bruno Taut and Burle Marx, and 25% answered Zumthor, Tanizaki and the presentations about Olafur Eliasson and Le Corbusier. Some students felt it was hard to specify the most important literature. The following lectures supported most their studies: 75% colour systems and colour tools (Pyykkö), 63% designer’s talk about landscape architecture and art (Berry), 50% colour in the detailed plan and urban design context (Pyykkö), 38% the opportunities of lighting (Siiroinen) and designer’s talk about interior architecture (Meuronen).

I asked about the three pedagogical principles: 1) new practices and rules for a web-based educational environment; 2) pedagogical methods for connecting people during the course; 3) methods for building the experience of colour, light and space on the web.

- The students named the lectures, the breaks, the structure of the course, the long-term working during the entire spring term, the breakout sessions and working in small groups, «as well as the different type of approach such as literature, the colour walk, assignments supported my learning, despite the fact that we didn’t meet in person».

- According to the students, the connection was built with the working in breakout rooms, in the discussions of the literature seminars, working in the small groups in assignments 3 and 4AB. They appreciated the long-term co-working in task 4AB and the mutual learning from each other by working with students from other disciplines. The atmosphere of the course was encouraging, and they thanked the teacher’s amazing attitude: «The best course in the corona time, humane and encouraging».

- As to the question on building the experience, the students answered: «The experience about colour, light and space broadened little by little». The lectures of the professionals, the literature seminars and discussions, the diverse backgrounds of the students, the personal and the shared experiences, and task 3, Analysis of the architectural atmosphere, supported their understanding and learning. «Percifal made me look at the physical environment more analytically».

Teacher’s experience

From the perspective of a teacher with 25 years of teaching experience, the course meant more than learning new software. It forced one to study new practices on a web-based educational environment, to evaluate all earlier assignments, to add more tasks with watercolours, to consciously include the topic of experience in all meetings and discussions. All prework, planning the schedule and meetings, preparing the material for the web, organizing small group discussions in breakout rooms, familiarizing oneself with student’s work, and writing e-mails, tripled the teacher’s workload.

Scientific knowledge of such matters how to avoid Zoom fatigue (Epstein, 2020) and promote the mental and physical wellbeing of the students grew «more and more» important during the course. The teachers were encouraged by the university to organize breakout room sessions, and thus to augment the co-operations between students. The students of Aalto University are hard-working and ambitious, so they needed continuous reminding of how many hours they ought to use for each task. «The course is a learning process» or «It will be sufficient to use 20 hours for this task». Covid-19 changed the curriculum of two students, and they needed to break away, but 18 of the 20 students completed the course. The course does not have numerical evaluation, only «pass or fail». Despite that, I could have given the best grade to almost every student for their excellent participation in the web-based course in this demanding situation.

The next course in 2022 (January to May) has been going partly with contact teaching in classrooms, partly on web-based education. New practices and rules for a web-based educational environment have given skills and knowledge to solve a new challenge on how to teach the same time in a classroom and online, because some students could not participate due to Covid-19. Thus, pedagogical methods for connecting people during the course are still important. The grouping is still an essential start to the course and the small group studies in assignments. A good experience and feedback of breakout room sessions influence the teaching in the classroom. I try to add the small group discussions, not only the discussions with the main group. In the classroom we could finally discuss shared experience, which is highly important in this course. Thus, methods for building the experience of colour, light and space on the web, pointed out the importance of guiding visitors. The description and experience with all senses made the presentations vivid. The pandemic and web-based education revolutionized all university education. The future will show, which new methods and discoveries of online education will permanently prevail.

Conclusion

Converting the experience-based university course about colour, light and space for the web is based on scientific knowledge about the new educational environment. Based on the findings of this case study, three pedagogical principles were identified: 1) new practices and rules of web-based educational environments aiming at avoiding multitasking, Zoom fatigue and at promoting well-being; 2) pedagogical methods for connecting people during the course such as discussions in breakout rooms, long-term group work and cooperation in assignments; 3) methods for creating the experience of colour, light and space across the web; for example, lecturers described the site and places through many senses, not only with images. The course started with a personal touch to colour and colour mixing with watercolours. The students used drawing, painting and other design methods in the main design assignments, not only relying on the computer. Thus, it was paradoxal that in this web-based course students rediscovered working with their hands. The feedback of one student summarizes this point: «I learnt a lot about colour, light and space. However, equally important was the teacher’s continuous reminding: don’t multitask, remember the breaks and that the estimated hours per task are sufficient».

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to The Finnish Cultural Foundation and Alfred Kordelin Foundation who have supported this research. I would like to thank all students for their participation, curiosity and interaction during the course. All visiting lectures influenced this course in important ways, especially Pentti Kareoja, who presented the main task and acted as a visiting critic. I thank Harald Arnkil for discussions about the «Colour-Light-Space» course and for his comments on this manuscript, and Francesca Valan who assisted with the Italian «Sommario».

References

Aargaard J. (2022), On the dynamics of Zoom fatigue, «Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies», vol. 0, n. 0, pp. 1-14.

Arnkil H. (2021), Värit havaintojen maailmassa, Espoo, Aalto ARTS Books, pp. 131-134. Engl. edition, Colours in the Visual World, Helsinki, Aalto University Schools of arts, Design and Architecture, 2013.

Arnkil H. e Pyykkö S. (2018), Color-Light-Space: an interdisciplinary course for graduate and postgraduate students, «Color Research and Application», vol. 43, n. 6, pp. 857-864.

Arnkil H., Fridell Anter K. e Klarén U. (2012), Colour and Light – Concepts and confusions, Helsinki, Aalto University.

Bailenson J. (2021), Nonverbal Overload: A Theoretical Argument for the Causes of Zoom Fatigue, «Technology, Mind, and Behavior», vol. 2, n. 1.

Böhme G. (2017a), Atmosphere, a Basic Concept of New Aesthetic (pp. 13-36); Atmospheres in Architecture (pp. 69-80); Light and Space (pp. 143-156). In A.-C. Engels-Schwarzpaul (a cura di), Atmospheric architectures: The Aesthetics of Felt Spaces, London-New York, Bloomsbury Academic.

Böhme G. (2017b), On Synestesia. In J-P. Thibaud (a cura di), The Aesthetics of Atmospheres, London-New York, Routledge, pp. 66-75.

De Heer J. (2009), The architectonic colour: Polychromy in the purist architecture of Le Corbusier, Rotterdam, 010 Publishers.

Delcampo-Carda A., Torres-Barchino A. e Serra-Lluch J. (2019), Chromatic interior environments for the elderly: A literature review, «Color Research and application», vol. 44, n. 3, pp. 381-395.

Epstein H.-A. B. (2020), Virtual Meeting Fatigue, «Journal of Hospital Librarianship», vol 20, n. 4, pp. 356-360.

Fridell Anter K. e Svedmyr Å. (2004), Mikä talolle väriksi, Helsinki, Kustannus Oy Hakkuri.

Gabriele S., Alice P., Alessandro R. e Maurizio R. (2020), The experience of the Master in Color Design and Technology during COVID-19 lockdown. In Y.A. Griber e V.M. Schindler (a cura di), The International Scientific Conference of the Color Society of Russia: Book of abstracts, Smolensk, Smolensk State University Press, pp. 177.

Ivanovic I. (a cura di), Proceedings of AIC 2016, Color in Urban Life: Images, objects and spaces, Interim Meeting of the International Color Association, pp. 56-59.

McLachlan F. (2012), Architectural colour in the professional palette, London-New York, Taylor & Francis Group.

McLachlan F., Neser AM., Sibilliano L., Wenger-Di Gabriele M. e Wettstein S. (2015), Colour strategies in Architecture, Basel, Haus der Farbe e Schwabe Verlag.

Pallasmaa J. (2016), Ihon silmät – arkkitehtuuri ja aistit, Helsinki, ntmo. Engl. edition, Eyes of the Skin – Architecture and the Senses, Chichester, John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

Porter T. e Mikellides B. (a cura di) (2009), Colour for Architecture Today, London-New York, Routledge e Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 23-49; 79-115.

Pyykkö S. (2016), Colours of a Neighborhood: Methodological Questions and Challenges. In Calvo

Pyykkö S. (2021), How to convert an experience-based university course about colour, light and space for the web? In Proceedings of the International Colour Association (AIC) Conference 2021, Milan, pp. 1133-1138.

Roto V., Bragge J., Lu Y. e Paucaskas D. (2021), Mapping Experience Research Across Disciplines: Who, Where, When, «Quality and User Experience», vol. 6, n. 1 e 7, pp. 1-26.

Serra Lluch J. (2019), Color for Architects, New York, Princeton Architectural Press, pp. 71-165.

Smedal G. (2001), Longyerbyen I farger. Og hva nå (Longyearbyen in colour. Status and challenges), Bergen, Eider.

Tanizaki J. (1997), Varjojen ylistys, Taide. Engl. edition, In Praise of Shadows, Sedgwick (ME), Leete’s Island Books, 1977.

Zumthor P. (2010), Thinking Architecture, Basel, Birkhäuser.

Sitography

Arnkil H. (2003), Mitä silmä kuulee ja korva näkee – Maalaustaiteen ja musiikin yhteyksistä, http://www.svy.fi/mita-silma-kuulee/ (consultato il 26 ottobre 2022).

Konstfack, 2E. PERCIFAL. Perceptual spatial analysis of colour and light, https://www.konstfack.se/syn-tes (consultato il 26 ottobre 2022).

Vol. 8, Issue 2, October 2022