Vol. 11, n. 2, ottobre 2025

APPROCCI INTERCULTURALI DELL’EDUCAZIONE

Educazione interculturale

Buone pratiche per formare cittadini globali nell’istruzione superiore

Melissa S. Ockerman,1Elisa M.F. Salvadori,2Marta Milani3 e Agostino Portera4,5

Sommario

Lo sviluppo di competenze globali e interculturali è fondamentale per vivere al meglio nelle nostre società multiculturali in continua evoluzione. L’istruzione superiore ha iniziato ad affrontare questa sfida attraverso l’adozione diffusa di strategie di informazione e comunicazione (ICT) e di e-learning. Una di esse, il programma di scambio virtuale «Global Learning Experience» (GLE), ha offerto un’opportunità significativa per organizzare esperienze di apprendimento internazionale collaborativo e, quindi, implementare lo sviluppo della competenza interculturale tra gli studenti e le studentesse universitari di counseling e servizio sociale. Nella presente ricerca qualitativa, mediante un questionario, gli autori hanno indagato le percezioni generali degli studenti sul GLE, i suoi benefici, le sfide e, soprattutto, la sua influenza sullo sviluppo della competenza interculturale. Nella sezione finale dell’articolo finale vengono presentate implicazioni e raccomandazioni basate sui risultati dell’indagine.

Parole chiave

Competenza interculturale, Educazione interculturale, Counseling interculturale, Formazione dei counselor, Scambio virtuale.

intercultural approaches to education

Intercultural Education

Best practices for educating global citizens in higher education

Melissa S. Ockerman,6Elisa M.F. Salvadori,7Marta Milani,8 and Agostino Portera9,10

Abstract

Developing global and intercultural competence proficiency is vital for thriving in our dynamically evolving multicultural societies. Higher education has begun to address this challenge through the widespread adoption of Information and Communications (ICT) and e-learning strategies. One such initiative, the «Global Learning Experience» (GLE) virtual exchange program, offered a significant opportunity to organize collaborative international learning experiences and thus cultivate the development of intercultural competence amongst graduate-level counseling and social work students. In the present qualitative research, using a questionnaire, the authors investigated students’ overall perceptions about the GLE, its benefits, challenges, and, importantly, its influence on students’ development of intercultural competence. The final article section presents implications and recommendations based on our findings.

Keywords

Intercultural competence, Intercultural education, Intercultural counseling, Counselor education, Virtual exchange.

Introduction

In the present period of post-modernity, globalization has caused «the intensification of worldwide social relations which link distant localities in such a way that local happenings are shaped by events occurring many miles away and vice versa» (Held, 1991, p. 9). All over the planet, human beings depend on each other and need to cope with many commune challenges related to many opportunities, but also risks in terms of climate, pollution, economic delocalization, violence, and wars. The transformation of time and space has also affected interpersonal relations: societies have become more multicultural and once-impossible interactions and exchanges have become routine. Increasing in the last decade, governments, international organizations, educators, politicians and business leaders are focusing on the significance of mobility and exchanges in the field of education through the mobility of students and teachers, for improving international understanding, interaction and better communication in the world.

In Europe, The Council of Europe aims to promote multicultural or intercultural dialogue, understanding, and competences. Mobility (real or virtual) drives students’ and teachers’ interactive learning and learning to live together. Togetherness goes beyond traditional social learning by focusing no longer on the individual but on collective groups. Most social and educational goals (interaction, inclusion, solidarity, joint responsibility, community building, global awareness) cannot be achieved by isolated individuals but only through learning together in diversity. Because learning takes place not only in the minds of individual learners but also in their social and cultural environment, the encounter with the «strangers» is the best way for the joint development of intercultural competence (IC). Intercultural understanding and intercultural encounters are more important than ever because they make it possible to address the causes of some of the most virulent problems of today’s societies in the form of misunderstandings across cultural, socio-cultural, ethnic and other lines: discrimination, racism, hate speech, etc.

Accordingly, today, many international organizations, as well as national ministries and private foundations, welcome and support international school partnerships and intercultural exchanges as part of a solid approach to intercultural learning in schools. International school cooperation effects range from strengthening intercultural learning to an impact on peace, human rights, and environmental education. In addition, school partnerships improve school quality, deepen the international dimension in the classroom, enhance the pedagogy of teaching and learning, and contribute to the social cohesion of societies worldwide.

Today, in our diverse democratic societies, education is urgently needed, which can help citizens live together by adequately and constructively interacting with diversity. There is an enormous need to develop IC (Portera, 2017). In the past, there have traditionally been two approaches: multicultural and intercultural. Multicultural education uses learning about other cultures to enhance acceptance, or at least tolerance. Intercultural education aims to go beyond passive coexistence to achieve a developing and sustainable way of living together in multicultural societies by creating an understanding of, respect for, and dialogue between different cultural groups.

The following manuscript present a research project aimed at developing proficiency in IC at the level of higher education by adopting communications and e-learning strategies. The aim will be to offer graduate students significant opportunities to organize collaborative international learning experiences and develop IC amongst global learning experiences through a virtual exchange program. The intercultural approach applied in this project builds on the positive elements of multicultural (understanding and respecting diversities) and transcultural models (recognizing commune elements, like values, norms and rules) and adds the opportunity of encounter, dialogue, handling conflict, and interaction. It can be considered a new Copernican revolution since concepts such as «identity» and «culture» are no longer understood as static but rather as dynamic processes in constant development and evolution. Encounters with «the foreign» and with ethnically and culturally different people represent opportunities for comparison and reflection regarding ideas, values, rules, and behavior.

Intercultural Competence to Face Today’s Complexity

In the twenty-first century, using information and communication technologies (ICT) for teaching and learning has become normal and part of both extracurricular and curriculum activities. In fact, there are many benefits from their use: 1. enhancement of participation in interactive exchanges and the related enhancement of language proficiency; 2. digital skills for learning; 3. ability to analyze, self-assess one’s abilities and identify learning needs; and 4. development of IC. In this sense, a virtual exchange, entitled, the «Global Learning Experience» (GLE), provided an ample opportunity not only to structure collaborative international learning experiences amongst graduate level counseling students in Chicago and social work students in Italy (Ockerman et al., 2023), but also to help them to be more appropriate and effective in their interactions in a multicultural context. A context that, thanks to the virtual platform, became a reflection of the Vygotskian conception of learning (Vygotsky, 1978) and Bachtin’s theory on dialogue (Ponzio, 1981). Indeed, operating within a digital platform allowed competence to be modulated through real negotiation processes, in a constant interplay between context and learning. This, in Bachtin’s notion of dialogue, means that the participants do not simply sift between competing meanings to find the correct one, but instead navigate a constantly changing and emerging hermeneutic environment. Yet what does it mean to become competent?

The theoretical debate on the construct of «competence» constitutes a field of discussion that is still open and interdisciplinary (Portera, 2022; Milani, 2017). Within the educational-scholastic context, in particular, competence emerges as a concept capable of orienting perspectives on teaching, learning, and assessment; for this reason, a pedagogical approach based on it represents a genuine educational paradigm shift (Castoldi, 2017).

In the Italian pedagogical landscape, a shared definition of competence is the one that frames it as the «ability to cope with a task, or a set of tasks, by managing to set in motion and orchestrate one’s own internal, cognitive-affective, and volitional resources, and to use the available external ones coherently and fruitfully» (Pellerey, 2004, p. 12) or, said otherwise, as the «ability of a subject to combine potentialities, starting from the cognitive, emotional and value resources available (knowledge, attitudes/awareness of the feelings, skills) to achieve not only controllable performance, but also intentional ones to reach the development of educational and training goals» (Alessandrini & De Natale, 2015, p. 1).

It follows that competence does not exist per se but is rather to be considered as an attribute of competent subjects (Milani, 2019). Its exercise therefore requires multiple dimensions, which will have to be involved in its manifestation: willingness, availability, motivation, and autonomy which, moreover, make it dynamic and processual, inherently susceptible to continuous improvement (Milani, 2017; Deardorff, 2009). Moreover, its evaluation is linked to social recognition and varies as the specific context in which it is manifested varies (Milani, 2019; Batini, 2013; Castoldi, 2017): in similar situations but in different contexts a person might, in fact, not always be evaluated as competent.

On the other hand, the intersubjective, relational and dialogical aspect implicit in the construct of competence is crucial when dealing with its specific declination constituted by IC. Giving an univocal definition of it is a rather difficult task, since there is a wide range of expressions in the literature that reflect the complexity of the term; some examples include: intercultural competences, intercultural communicative competence, global competence, multicultural competence, transcultural competence, cultural competence, intercultural sensitivity, cross-cultural awareness, cultural literacy and cross-cultural capability (Deardorff, 2012; Fantini, 2009). Among them assumes — in the context of the purposes of the present study — an interesting significance, the so-called «global competence» (OECD, 2023; Ferrero, 2022; OECD, 2020; Rensink, 2020), defined as a multidimensional capacity through which people can examine local, global or cross-cultural issues, understand the different perspectives and views there may be on the world, interact successfully with the Other, and implement actions for the collective well-being and the environment (Pedrizzi, 2023). Therefore, a path that aims to develop global competence for the formation of citizens of the world able to coexist peacefully and democratically, recognizes the need to accompany the younger generations in a contemporary world of uncertainties, facilitating those competences — primarily intercultural — capable of looking at the global and local in an integrated and inclusive form. It may therefore be said that IC is embedded in the epistemological framework of global competence, constituting a fundamental specification of it.

Among the various definitions given to the construct, we recall those of Portera, who sees it as «the set of characteristics, knowledge, attitudes, and skills designed to successfully manage relationships with linguistically and culturally diverse people» (Portera, 2013, p. 144); of Santerini, for whom it is «a dynamic mix of knowledge and skills that indicate the achievement of mastery in a given professional environment» (Santerini, 2010, p. 190), further adding that the concept of competence can also be understood as proficiency, i.e., «a high-level internalized knowledge related to the ability to read, analyze specific complex situations» (Santerini, 2010, p. 190). Moreover, Barrett, Lázár, Mompoint-Gaillard and Philippou (Huber & Reynolds, 2014) describe it as a combination of attitudes, knowledge, understandings, and skills applied through actions that enable, individually or with others to:

- Effectively understand and respect people who have different cultural affiliations than oneself;

- Respond appropriately, effectively, and respectfully when interacting and communicating with culturally different people;

- Establish positive and constructive relationships with culturally different people;

- Understand oneself and one’s multiple cultural affiliations through encounters with different cultures.

However, the most recurrent trait seems to be building appropriate and effective relationships. For most authors, the elements of competence that enable this to be achieved consist predominantly of knowledge (and related understanding), skills, and attitudes. As for the cognitive dimension, it involves acquiring broad cultural and socio-linguistic knowledge and developing abilities to critically interpret global historical, political, and social aspects by going beyond superficial elements such as customs, food, or other similar aspects. Skills, on the other hand, concern the ability to establish and maintain relationships, the ability to communicate with minimal loss or distortion, and cooperating to accomplish tasks or satisfy mutual interests or needs. They can thus be divided into cognitive, communicative, and social-emotional skills, and basically concern the ability to execute a well-organized and complex pattern of thought and behavior to achieve the goal. Finally, the area of attitude, in which it conveys the so-called «intercultural sensitivity», that is «an individual’s ability to develop emotion towards understanding and appreciating cultural differences that promotes appropriate and effective behaviour in intercultural communication» (Chen & Starosta, 1996, pp. 353-383). Within this dimension, there is a component related to emotions, one to cognition through understanding differences, and one related to action; although the focus remains on the emotion generated by people, situations, and contexts. It is prefigured as a necessary precondition for making exchange and dialogue fruitful and fostering the full activation of IC. A final key focus concerns context, that is, the availability of adequate time, space, and resources (both human and material) for meeting and interaction, as well as the quality of interpersonal relationships: the type of relationship in place, the motivation to meet and dialogue.

As noted previously, the proliferation of ICT has become a more dominant vehicle in higher education to help foster IC. Below, we recount one such endeavor, the GLE, discuss our findings, and provide lessons learned.

GLE Brief Introduction

Overview of the Program

Faculty in DePaul University’s (Chicago) counselor education program and the University of Verona’s Centro Studi Interculturali social work program collaborated for two years to create an effective virtual cross-cultural experience. Specifically, researchers were interested in determining how, if at all, a virtual Global Learning Experience (GLE; often referred to as Collaborative Online International Learning [COIL]) impacted their IC.

Context and Setting

During a six-week collaborative GLE project in Spring 2022, we examined how graduate-level clinical mental health counseling (DePaul University) and social work students (University of Verona) collaborated with their respective cities to broker community assets germane to youth and their families. Students worked in groups to analyze local resources and created a community asset map (Griffin & Farris, 2010). The aim of this assignment was to help students identify community resources appropriate for their targeted population (e.g., multiple spoken languages, cost-effective payment options, accessibility via public transport, etc.) and to underscore the importance of collaborating across sectors to provide comprehensive wrap-around services. Each local community group was assigned to a corresponding international community group. Subsequently, students worked with their international groups to analyze their community maps and complete a case study, thereby broadening their global perspectives about community-building and its impact on their future professional roles.

Given the escalating refugee population in Verona (IDOS, 2022), and the increasing demand in Chicago to aid immigrants,11 the project placed special emphasis on identifying community resources for the well-being of immigrant and refugee children and their families.

Numerous studies indicate the ethical necessity for culturally competent mental health counselors and social workers working with immigrant and refugee populations. Indeed, IC impacts the efficacy of the working relationship across helping professions (Bhuyan et al., 2012).

Overview of the study: aim, tools, participants, and data analysis

To investigate the participants’ IC, specifically the project’s role and effect on the participants’ IC, a questionnaire (in both English and Italian) with closed and open-ended questions was used. The questionnaire structure is based on Deardorff’s model of IC (Deardorff, 2006, 2009, 2011).

The pre-project survey consisted of two parts: a first part of 15 self-assessment questions concerning the components of IC and a second, more reflective part, consisting of two open-ended questions. The post-test consisted of a first part identical to the pre-test followed by some open-ended questions about each item. The second part of the post-test included three questions designed to bring out how the project had impacted the participants’ IC.

The target population included 45 students, 35 females and 10 males between the ages of 22-70, enrolled in CSL 520 «Counseling Children and Adolescents» (DePaul University) or enrolled in a master program in Intercultural Education and Competences (University of Verona).

The qualitative data analysis methodology followed the six steps of Braun & Clarke’s reflective thematic analysis (Braun e Clarke, 2006, 2019). This work’s outcome was a codebook in which the main themes with respect to IC that emerged from the questionnaire, brief definitions, and examples (cited from the questionnaire) were identified.

The IC components identified at the end of the project were:

Knowledge

Of Language

Of Self

Of cultural systems and/or institutions

Of other cultures

Attitude

Openness

Display (action)

Open mindness

Feel

Ability to share

Patience

Giving of time/ability to wait to make/suspend judgment

Awareness

Of Self

Of Communication Styles

Careful/considerate of others

Curiosity

Skill

Evaluate

Adapting

Communication Modes

Speaking slowly

Speaking calmly

Analyze

Compare/Contrast

Verify/Check

Relate

Anticipate Need

Ability to Plan

Check Bias

Observation

Empathy

Attention to Non-Verbals

Eye-contact

Smiling

Ability to ask questions

Reflecting

Engage in discussion/debate

Listen

Paraphrase

Ability to Engage in Team

Attention to Context/Environment

Exposure to diverse experiences/people

Flexibility

Exploring Intercultural Competence

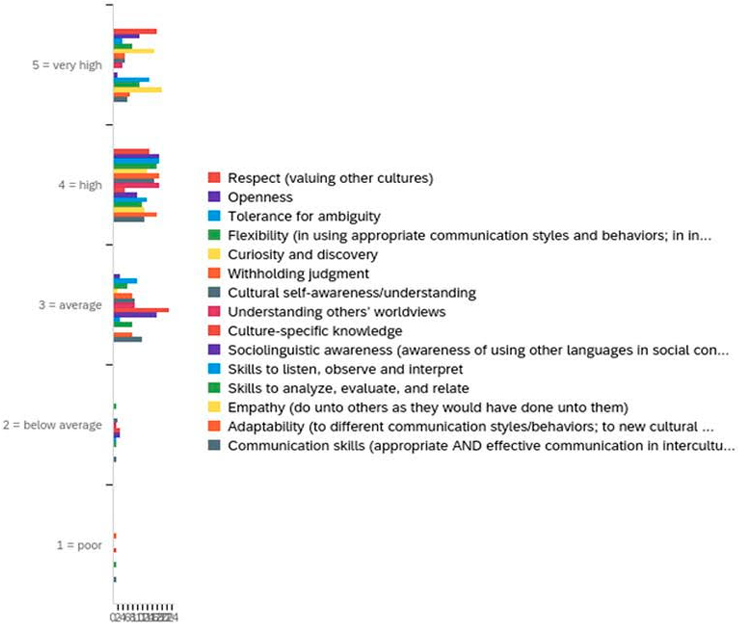

Concerning the quantitative data, the pre-test questionnaire was completed by 33 students, while 20 students completed the post-test (the questionnaire was not mandatory) (figure 1).

Figure 1

IC in the pre-test

Below are some reflections with respect to the data collected:

- The pre-test shows that, in general, students believe they have good IC. In fact, the assigned values are concentrated between the 3rd and 5th level (highest). It can be seen from Figure 1 that the three highest scoring skills were Empathy, understood as «do unto others as they would have done unto them», which was placed at level 5 by 60.6% of the students, Respect (valuing other cultures), placed at the highest level by 54.5% of the participants, and Curiosity & Discovery which was listed as highest by 51.5% of the participants.

- At the end of the project, the skills that were rated highest (level 5-very high) were Respect (52.6%), and Curiosity & discovery, Withholding judgment, and Empathy, the latter three placed at level 5 by 45% of the participants. In addition to this, the items whose level 5 increased the most were Withholding judgment (in the pre-test it was placed as level 5 by only 15.15% of participants, while in the post-test it increased to 45%), Tolerance for ambiguity (pre-test level 5 indicated by 12.12% and post-test indicated by 36.84%), and Cultural self-awareness/understanding (pre-test 15.15% and post-test 35.00%). Referring back to the structure and specific objectives of the project, it is interesting to note that the items Culture-specific knowledge and Sociolinguistic awareness, again for Level 5, went from very low values (0% and 6.06%, respectively) to higher values at the end of the project (Culture-specific knowledge: 15%; Sociolinguistic awareness: 25%). This would lead to the assumption that the project helped enhance these two skills.

- Interestingly, the number of people who assigned themselves a score of 5 on the skills to listen, observe, and interpret decreased, moving to levels 4 and 3. Similarly, students rated themselves empathic at levels 4 and 3 increased, while 5 significantly decreased. This may be due to a predisposition towards socially desirable answers, which may have initially influenced or distorted participants’ views. It may also indicate that participating in the GLE gave students a more critical and reflective view of these competences, allowing participants to better understand them, and thus, the growth still necessary to possess them at the highest level.

In the post-test, each self-assessment prompt related to the individual competence item was accompanied by an open-ended question to stimulate reflection. For example, by asking the participants to present how certain IC components were acted upon within the project.

The wording of these open-ended questions contains a strong connection with reality and practice, as well as enacted in a specific situation of IC. In particular, those questions asked participants to provide examples of the skills and competences they displayed during the GLE project and, at the same time, stimulate reflection on their actions, which are often acted out unconsciously and automatically.

Students demonstrated openness mainly in their ability to relate the two referral systems (Italy and the U.S.), often through active listening and requests for clarification, as illustrated by the following responses:

I displayed openness by working with Italy to understand their way of operating through challenges relating to various areas of someones life.

Special attention was also paid to elements that may hinder or facilitate the action of skills. This prompt led the students to report skills they possess that worked positively in the project and those skills that may have challenged them. Many of the difficulties related to flexibility were related to the dimension of communication, for example, one student pointed out:

I think flexibility is so important! Also it was hard because in my group I was the only one speaking in English so I had to find all the correct word for explain […]

The request to reflect on the possibility of acting out specific skills within the project was also intended to emphasize how skills are shown in practice rather than which ones we would like to possess. Some of the responses mainly concerned knowledge of the culture of the two countries (Italy and the US). Such knowledge enabled students to better understand the organization, functioning, and differences between the two social health systems, including the needs of clients, as can be seen from the following responses:

Being conscious of Italy’s history, culture, geo-political positioning, government structure, neighboring country relations, etc., really helps inform an understanding of why certain services are provided a certain way compared to the US.

Some responses highlighted students’abilities concerning service providers and users. For example, the ability to anticipate and understand the real needs of users. Also, the ability to reflect on the correspondence between needs and services, including through their empathic skills.

Alternatively, again, the ability to consider context as an element of design:

When reading their community map resources, I made sure to consider the various factors influencing their experience vs. ours. How large is Italy and Verona geographically? What neighboring countries do they have? How has the history of culture and government impacted community resources? How does the US differ in these areas?

Fostering Intercultural Competence

The last open-ended questions of the questionnaire were intended to investigate IC development within the project further. This qualitative component reinforces the professional’s ability to question and reflect on their actions, evaluate them, and possibly modify them (Mortari, 2003; Schön, 1993). Such reflection can foster an increase in competence, as reflecting and questioning one’s actions can develop awareness concerning one’s skills (Mortari, 2003), and fostering awareness regarding one’s skills and abilities leads to an increase in empowerment (Galavotti, 2020). Moreover, reflective capacity is essential to analyze what one does and to evolve and modify one’s practices.

Regarding the skills that supported students during the project, the responses covered both personal attitudes such as being outgoing, patient and adaptable, flexible, open to learning, and curious, but also students learned skills such as knowledge of other languages, systems, and social phenomena, and social skills.

Many responses highlighted the functional skills of the project, such as confrontation with different groups of people, discussion, dialogue, and interaction, all of which are core elements of intercultural pedagogy (Portera, 2020). Traveling, communicating, meeting different people, confronting different cultures, and «staying curious» were identified as possibilities for continuing to develop one’s IC.

Some responses also brought out knowledge, attitudes, or skills already possessed and used in the project, such as open-mindedness, flexibility, teamwork, contextual or background knowledge, and specific knowledge, for example about immigration and its process or the national health care system; «listening skills» and «knowing how to listen well», are cited as essential skills to be able to interact. The dimension of culture is mentioned in terms of one’s attitudes or in the form of awareness.

One of the final questions encouraged students to reflect on their abilities discovered through project participation. In addition to flexibility, empathy, and new knowledge, emerged also the ability to be open to the other and the world; change one’s point of view; not to take anything for granted. In addition, the ability to read and interpret contexts and to be able to «widen our gaze» to catch elements that were not previously considered were also reported:

It appears some countries/communities have a government healthcare approach of «how can we help you» (universal healthcare, healthcare as a right) vs. «how can you help yourself» (healthcare as a privilege, not free, etc.).

Lessons Learned

The post-assessment deliberately sought the insights of students, aiming to gather not only their acquired knowledge but also their recommendations for refining future iterations of the project. As is customary in most iterations of virtual exchange, students identified language barriers, the challenges of navigating time zone differences, and understanding cultural nuances. They acknowledged the strategic placement of at least one English-speaking member within each Italian group and the employment of a translator for the joint synchronous class discussion (Ockerman et al., 2023).

Adhering to best practices, the GLE was meticulously structured in three distinct phases: firstly, an empathy-building stage fostered community through introductory student and instructor pictures and videos, probing discussion topics, and supplementary readings on cultural similarities and differences; secondly, a collaborative work phase entailed group project deliverables necessitating negotiation, organization and cooperation. Lastly, a reflective phase provided students ample opportunity to consider their individual growth and learnings from the cross-national encounter. As corroborated by research (Doescher & Rubin, 2022; Helm & Van der Velden, 2019; O’Dowd, 2021), these methodologies effectively pushed students beyond their conventional classroom boundaries.

In anticipation of forthcoming iterations, we have deliberated the necessity for more comprehensive preparatory materials describing welfare services in each participating country from the project’s outset. This includes assignments involving participant interviews to enhance engagement and understanding. Additionally, integrating a mid-project monitoring mechanism and allocating time for peer tutoring or mentoring to bolster student support are under consideration. Lastly, efforts are underway to establish an in-person summer exchange program between the two universities as a culminating experience.

Conclusion

This article presents a research project to develop proficiency in IC in higher education by adopting communications and e-learning strategies. The aim was to offer graduate students significant opportunities to organize collaborative international learning experiences and develop IC amongst global learning experiences through a virtual exchange program. Faculty at DePaul University and the University of Verona’s Centre for Intercultural Studies collaborated for two years to generate an effective virtual GLE through Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) to impact IC.

To conclude, it is possible to affirm that encounters between people from different countries and cultures, even if virtual, if adequately planned and conducted, can generate significant professional, personal, and social enrichment. Although the short time, the fiscal distance, and all the difficulties faced, each one of the involved people, students, and staff, have had the opportunity to have highly significant experiences of actual and constructive encounters. The GLE project could be easily reproduced in other universities and schools. The hope is that it could be useful for confronting neoliberal and socially unjust praxis in order to overcome various historical failures, such as the alarmingly low educational success of students with immigrant and low socioeconomic backgrounds (European Commission, 2024).

Today, in our schools and universities, there is an urgent need to initiate an authentic change in order to develop innovative approaches necessary for replacing current school paradigms based on the tenants of the military and Fordism and for enhancing all the potential, talents and multiple intelligences (Gardner, 1993) of every young person.

Bibliography

Alessandrini G. & De Natale M.L. (2015), Il dibattito sulle competenze. Quale prospettiva pedagogica, Bari, Pensa MultiMedia.

Batini F. (2013), Insegnare per competenze, Torino, Loescher.

Bhuyan R., Park Y. & Rundle A. (2012), Linking practitioners’ attitudes towards and basic knowledge of immigrants with their social work education, «Social Work Education», vol. 31, n. 8, pp. 973-994.

Braun V. & Clarke V. (2006), Using thematic analysis in psychology, «Qualitative Research in Psychology», vol. 3, n. 2, pp. 77-101.

Braun V. & Clarke V. (2019), Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis, «Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health», vol. 11, n. 4, pp. 589-597.

Castoldi M. (2017), Valutare e certificare le competenze, Roma, Carocci.

Chen G.M. & Starosta W.J. (1996), Intercultural communication competence: A synthesis, «Communication Yearbook», vol. 19, pp. 353-383.

Deardorff D.K. (2006), Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization, «Journal of Studies in International Education», vol. 10, n. 3, pp. 241-266.

Deardorff D.K. (Ed.) (2009), The Sage Handbook of Intercultural Competence, Thousand Oaks, Sage.

Deardorff D.K. (2011), Assessing intercultural competence, «New Directions for Institutional Research», vol. 149, pp. 65-79.

Deardorff D.K. & Jones E. (2012), Intercultural competence. In D.K. Deardorff, H. de Wit, J. Heyl e T. Adams (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of International Higher Education, Thousand Oaks, Sage, pp. 13-15.

Doscher S. & Rubin J. (2022), Introduction to What Instructors and Support Staff Need to Know About COIL Virtual Exchange. In J. Rubin & S. Guth (Eds.), The Guide to COIL Virtual Exchange: Implementing, Growing, and Sustaining Collaborative Online International Learning (1st ed.), New York, Routledge.

European Commission (2024), Report of PISA 2022 study outlines worsening educational performance and deeper inequality, Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union.

Fantini A.E. (2009), Assessing intercultural competence: Issues and tools. In D.K. Deardorff (Ed.), The Sage Handbook of Intercultural Competence, Thousand Oaks, Sage, pp. 456-476.

Ferrero V. (2022), Competenze non cognitive, equità e sviluppo olistico della persona. Riflessione pedagogica e spunti di lavoro, «Q-TIMES Webmagazine», vol. 14, n. 2, pp. 41-52.

Galavotti C. (2020), Approccio narrativo e servizio sociale: raccontare di sé e raccontare dell’altro. La metodologia narrativa come strumento per l’assistente sociale, Santarcangelo di Romagna (RN), Maggioli.

Gardner H. (1993), Multiple Intelligences, New York, Basic Books.

Griffin D. & Farris A. (2010), School counselors and collaboration: Finding resources through community asset mapping, «Professional School Counseling», vol. 13, n. 5, pp. 248-256.

Held D. (Ed.) (1991), Political Theory Today, Stanford, Stanford University Press.

Helm, F., & Van der Velden, B. (2019). Erasmus+ virtual exchange: intercultural learning experiences: 2018 impact report. https://op.europa.eu:443/en/publication-detail/-/ publication/a6996e63-a9d2-11e9-9d01-01aa75ed71a1

Huber J. e Reynolds C. (Ed.) (2014), Developing Intercultural Competence Through Education, Strasbourg, Council of Europe Publishing.

IDOS (2022), Dossier statistico immigrazione, Roma, IDOS.

Milani M. (2017), A scuola di competenze interculturali. Metodi e pratiche pedagogiche per l’inclusione scolastica, Milano, FrancoAngeli.

Milani M. (2019), Pedagogia e competenza interculturale: Implicazioni per l’educazione, «Encyclopaideia», vol. 23, n. 54, pp. 93-108.

Mortari L. (2003), Apprendere dall’esperienza. Il pensare riflessivo nella formazione, Roma, Carocci.

Ockerman M., Milani M., Salvadori E. & Portera A. (2023), Global Learning Experience: Developing Intercultural Competence Through Virtual Exchange, «Education Sciences & Society», vol. 14, n. 3, pp. 288-309.

O’Dowd R. (2021), Virtual exchange: Moving forward into the next decade, «Computer Assisted Language Learning», vol. 34, n. 3, pp. 209-224.

OECD (2023), Teaching for the Future: Global Engagement, Sustainability and Digital Skills, International Summit on the Teaching Profession, Paris, OECD Publishing. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1787/d6b3d234-en

OECD (2020), PISA 2018 Results (Volume VI): Are Students Ready to Thrive in an Interconnected World?, Paris, OECD Publishing. Doi:https://www.oecd.org/publications/pisa-2018-results-volume-vi-d5f68679-en.htm

Pedrizzi T. (2023), Competenze globali: preparare i nostri giovani per un mondo inclusivo e sostenibile. Il Framework di «Competenza Globale» di OCSE PISA. https://orientamentipedagogici.weebly.com/uploads/1/9/1/7/19170051/pedrizzi_pisa_2018_competenze_globali.pdf

Pellerey M. (2004), Le competenze individuali e il portfolio, Milano, RCS Libri.

Ponzio A. (1981), Signs, Dialogue and Ideology, Amsterdam, J. Benjamins.

Portera A. (a cura di) (2013), Competenze interculturali. Teoria e pratica nei settori scolastico-educativo, giuridico, aziendale, sanitario e della mediazione culturale, Milano, FrancoAngeli.

Portera A. (2017), Intercultural competences in education. In A. Portera & C.A. Grant (Eds.), Intercultural Education and Competences for the Global World, Cambridge, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 23-46.

Portera A. (2020), Manuale di pedagogia interculturale, Bari, GLF editori Laterza.

Portera A. (2022), Educazione e pedagogia interculturale, Bologna, il Mulino.

Rensink C. (2020), Global competence for today and the future, «Childhood Education», vol. 96, n. 4, pp. 14-21.

Santerini M. (2010), Intercultural competence teacher-training models: The Italian experience. In Educating Teachers for Diversity. Meeting the Challenge, Paris, OECD Publications.

Schön D.A. (1993), Il professionista riflessivo: Per una nuova epistemologia della pratica professionale, Bari, Dedalo.

Vygotskij L. (1978), Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

-

1 Professore, Coordinatore del Servizio di Counseling Scolastico, Responsabile del Programma di Counseling, Membro del Consiglio Universitario per le Attività Sportive, Dipartimento di Scienze della Formazione, DePaul University, Chicago, Illinois.

-

2 Assegnista di ricerca, Università degli Studi di Verona.

-

3 Professoressa associata di Pedagogia Generale e Sociale, Università degli Studi di Verona.

-

4 Professore ordinario di Pedagogia Generale e Sociale e di Pedagogia Interculturale, Università degli Studi di Verona.

-

5 Gli autori hanno contribuito collegialmente alla stesura dell’articolo. Tuttavia, Agostino Portera ha redatto l’introduzione e la conclusione; Marta Milani è autrice del paragrafo La competenza interculturale per affrontare la complessità odierna; Melissa Ockerman è autrice dei paragrafi Breve introduzione al GLE e Lezioni apprese; Elisa M.F. Salvadori è autrice dei paragrafi Panoramica dello studio: obiettivi, strumento, partecipanti e analisi dei dati, Esplorare la competenza interculturale e Promuovere la competenza interculturale.

-

6 Professor, School Counseling Coordinator, Counseling Program Chair, University Athletic Board, DePaul University Athletics, College of Education, Chicago, IL.

-

7 Research Fellow, University of Verona.

-

8 Associate Professor of General and Social Pedagogy, University of Verona.

-

9 Full Professor of General, Social and Intercultural Pedagogy, University of Verona

-

10 The authors collegially contributed to the preparation of the paper. However, Agostino Portera wrote the introduction and the conclusion; Marta Milani is the author of paragraph Intercultural Competence to Face Today’s Complexity; Melissa Ockerman is the author of paragraphs GLE Brief Introduction and Lessons Learned; Elisa M.F. Salvadori is the author of paragraphs Overview of the study: aim, tool, participants, and data analysis, Exploring Intercultural Competence and Fostering Intercultural Competence.

-

11 American Immigration Council, Annual Report 2022, https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org (accessed July 10, 2023).

Vol. 11, Issue 2, October 2025