Invited articles / Invited articles

Claremont Purpose Scale: psychometric properties of the Italian validation for workers

Claremont Purpose Scale: psychometric properties of the Italian validation for workers

Annamaria Di Fabio

Department of Education, Languages, Intercultures, Literatures and Psychology (Psychology Section), University of Florence.

Maureen E. Kenny

Lynch School of Education, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA, USA

Sommario

Lo scopo del presente lavoro è di analizzare le proprietà psicometriche della versione italiana della Claremont Purpose Scale (CPS) per il suo utilizzo nel contesto italiano con lavoratori. La CPS è stata somministrata a 224 lavoratori. Sono state verificate dimensionalità, attendibilità e validità concorrente. L’analisi fattoriale confermativa ha supportato la versione a tre dimensioni del questionario. La coerenza interna e la validità concorrente sono soddisfacenti. I risultati indicano che la versione italiana della CPS risulta un valido strumento per rilevare il purpose anche nel contesto italiano con lavoratori.

Parole chiave

purpose; psychometric properties; Italian version of the Claremont Purpose Scale (CPS).

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to analyze the psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Claremont Purpose Scale (CPS) for its use in the Italian context among workers. The CPS was administered to 224 workers. Dimensionality, reliability, and concurrent validity were investigated. Confirmatory factor analysis supported a three-dimensional version of the questionnaire. Satisfactory internal consistency and concurrent validity were found. Results indicated that the Italian version of the CPS is a valid instrument for detecting purpose also in the Italian context among workers.

Keywords

purpose; psychometric properties; Italian version of the Claremont Purpose Scale (CPS).

The discovery of a life purpose is a process of development that often intersects with the formation of a healthy identity (Hill & Burrow, 2012). The development of identity and purpose are interconnected processes since as individuals consider who they hope to become, they also reflect on what they hope to achieve in their lives (Bronk, 2011). Purpose is considered a resource for personal development, a key aspect for thriving (Bundick, Yeagar, King, & Damon, 2010) and a central dimension of psychological well-being (French & Joseph, 1999; Ryff, 1989). Purpose is also associated with physical health, related to better cardiovascular health, better sleep quality, and greater longevity (Boyle, Barnes, Buchman, & Bennett, 2010; Hill & Turiano, 2014; Ryff, Singer, & Love, 2004; Turner, Smith, & Ong, 2017). Given the psychological and physical benefits associated with leading a life of purpose, having valid and reliable measures to assess purpose is fundamental for advancing research, intervention and evaluation (Bronk, Riches, & Mangan, 2018).

Purpose is defined as a long-term and far-sighted intention to achieve significant goals for oneself and for the broader world (Damon, Menon, & Bronk, 2003). This definition includes three essential dimensions (Bronk, Riches, & Mangan, 2018). First, purpose is characterized by its aim. It is not a short-term goal but rather a long-term aim that provides a sense of stimulation and lasting direction. Secondly, purpose in life is meaningful to the person, which is generally highlighted by the individual’s commitment of time, energy and resources in its pursuit. As a result of its personal meaning, one’s purpose in life is highly motivating. In fact, purpose has been described as the maximal source of motivation (Damon, 2008). Third, purpose is not just part of a personal search for meaning, but entails an external component. In particular, it is inspired, at least in part, by the desire to make a difference for the world in a broader sense. Individuals driven by motivations «beyond-the-self» differ from individuals who are more self-centered in their motivations. For example, studies have shown that compared to more self-focused individuals, those with a «beyond-the-self» orientation are more open, report higher levels of satisfaction in life and have more humanitarian and political dispositions (Bronk & Finch, 2010; Mariano & Vaillant, 2012). Most existing measures to assess purpose lack this third «beyond-the-self» dimension (Damon et al., 2003).

The Claremont Purpose Scale (CPS; Bronk, Riches, & Mangan, 2018) represents an instrument designed to assess purpose and its three fundamental dimensions: personal meaningfulness, goal orientation, and self-transcendence («beyond-the-self» dimension). Although previous instruments have not assessed the «beyond-the-self» aspect, the 12-item CPS is a valid and reliable measure of the purpose construct and its three dimensions (Bronk, Riches, & Mangan, 2018). The CPS was developed by Bronk, Riches and Mangan (2018) to measure purpose with adolescents and young adults in the US context. The CPS demonstrated good reliability for the total score (alpha = .94) and for each of the three dimensions: personal meaningfulness (alpha = .92), goal-orientation (alpha = .86), and beyond-the-self (alpha = .92) (Bronk, Riches, & Mangan, 2018). The CPS also demonstrated good concurrent validity, correlating positively with life satisfaction and inversely with depression (Bronk, Riches, & Mangan, 2018).

According to the theoretical framework described above, the aim of the present work is to analyze the psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Claremont Purpose Scale for its use in the Italian context and specifically with Italian workers. Since purpose has been associated with a range of psychological and physical well-being outcomes (Bronk, Riches, & Mangan, 2018), research assessing purpose could be applied for the development of healthy organizations and businesses (Di Fabio, 2017a, 2017b; Di Fabio & Peiró, 2018; Tetrick & Peiró, 2012). With this intent in mind, we assess the concurrent validity of the CPS by assessing the relationship of the CPS total and its dimensions with a range of indicators associated with reflectivity, well-being, life satisfaction, meaning, and thriving among Italian workers.

Method

Participants

Instruments were administered to 224 workers from the Tuscany Region (107 males – 47,77%, 117 females – 52,23%; mean age = 42,63 years, SD = 9,47).

Measures

Claremont Purpose Scale (CPS). To evaluate purpose, the Claremont Purpose Scale (Bronk, Riches, & Mangan, 2018) was administered, with the back-translation method used to create the Italian version of the CPS. The questionnaire is composed of 12 item with a response format on 5 point Likert scale and assesses three dimensions: Personal meaningfulness (example of item: «How clear is your sense of purpose in your life?»); Goal orientation (example of item: «How much effort are you putting into making your goals a reality?»); Self-transcendence – beyond the Self aspects (example of item: «How important is it that in your life you contribute to something beyond yourself?»). The psychometric properties of the Italian version of the CPS will be analyzed in the present study.

Life Project Reflexivity Scale (LPRS). To evaluate reflexivity, the Life Project Reflexivity Scale (LPRS; Di Fabio, Maree, & Kenny, 2018) was used. The scale is composed of 15 items with response options on a 5 point Likert scale (from 1 = «Strongly disagree» to 5 = «Strongly agree»). The scale provides a total score and scores on three separate dimensions: Clarity/Projectuality (example of item: «The projects for my future life are clearly defined»), Authenticity (example of item: «The projects for my future life are anchored by my most authentic values»), and Acquiescence (example of item: «My personal project is more anchored by the values of the society in which I live than my most authentic values»). The Cronbach alpha coefficients are: .86 for the total score; .89 for the Clarity/Projectuality dimension; .86 for the Authenticity dimension; and .83 for the Acquiescence dimension. Concurrent validity was established based on correlations with measures of life meaning and authenticity (Di Fabio, Maree, & Kenny, 2018).

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). To evaluate positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA), the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS, Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) in the Italian version by Terraciano, McCrae and Costa (2003) was administered. The PANAS is composed of 20 adjectives of which 10 refer to positive affect (e.g., enthusiastic, interested, determined) and 10 to negative affect (e.g., afraid, upset, distressed). Participants indicate how they generally feel based on a Likert scale ranging from 1 = «Very slightly or not at all» to 5 = «Extremely». The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were: .72 for positive affect and .83 for negative affect. Concurrent validity emerged as adequate (Terraciano, McCrae, & Costa, 2003).

Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS). To evaluate life satisfaction, the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS, Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) in the Italian version by Di Fabio and Gori (2016) was used. This scale consists of five items (e.g. «I am satisfied with my life», «The conditions of my life are excellent»), which are rated using a 7 point Likert scale ranging from 1 = «Strongly disagree» to 7 = «Strongly agree». Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .85 (Di Fabio & Gori, 2016). Concurrent validity was assessed as adequate (Di Fabio & Gori, 2016).

Meaningful Life Measure. To evaluate meaning in life, the Meaningful Life Measure (MLM, Morgan & Farsides, 2009) in the Italian version by Di Fabio (2014) was used. The questionnaire consists of 23 items, which are rated on a 7 point Likert scale ranging from 1 = «Strongly disagree» to 7 = «Strongly agree». The MLM identifies five dimensions: Exciting life (example of item: «Life to me seems always exciting»), Accomplished life (example of item: «So far, I am pleased with what I have achieved in life»), Principled life (example of item: «I have a personal value system that makes my life worthwhile»), Purposeful life (example of item: «I have a clear idea of what my future goals and aims are»), and Valued life (example of item: «My life is significant»). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were: .85 for the total score, .85 for Exciting life, .87 for Accomplished life, .86 for Principled life, .85 for Purposeful life, and .84 for Valued life. The MLM and its dimensions demonstrated good concurrent validity (Di Fabio, 2014).

Flourishing Scale. To evaluate flourishing, the Flourishing Scale (Diener et al., 2010) in the Italian version by Di Fabio (2016) was used. This instrument consists of 8 items with response options on a 7 point Likert scale ranging from 1 = «Strongly disagree» to 7 = «Strongly agree» (example of item: «I lead a purposeful and meaningful life»). The reliability of the scale is alpha = .88. Concurrent validity evidence is good (Di Fabio, 2016).

Procedure

The instruments were administered according to the requirements of privacy and informed consent of Italian law. The order of administration was counterbalanced to control the possible effects of presentation of the instruments.

Data Analysis

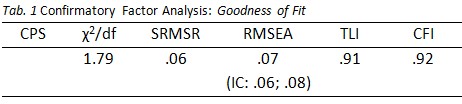

The factor structure of the Italian version of the CPS was verified through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) with AMOS version 6 (Arbuckle, 2005), using maximum likelihood method. The fit of the model was examined not only by referring to the value of χ2 given that this statistic is influenced by the high number of participants, but also by considering other fit indices such as the ratio between chi-square and degree of freedom (c2/df). Ratio (c2/df) values between 1 and 3 are considered indicators of a good fit (Byrne, 1989; Carmines & McIver, 1981; Marsh & Hocevar, 1985). We also considered the Comparative Fit Index (CFI, Bentler, 1990) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; Tucker & Lewis, 1973), with values greater than .90 indicating a good fit with the model (Bentler, 1990). We also considered the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA, Browne & Cudeck, 1993) and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMSR, Bentler, 1995), with values below .08 indicating a good adaptation of the model (Browne, 1990). The reliability of the CPS was also verified through the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Furthermore, to analyze concurrent validity, the Pearson r correlations of the CPS with the LPRS, PANAS, SWSL, MLM, FS were computed.

Results

To verify the factor structure of the CPS (Bronk, Riches, & Mangan, 2018) a Confirmatory Factor Analysis was carried out. The indices of Goodness of Fit are reported in Table 1.

In relation to the considered indices, the Italian version of the scale confirmed a three-dimensional structure.

Regarding reliability, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are: .90 for the total score, .81 for Personal meaningfulness dimension, .86 for the Goal orientation dimension, and .82 for the Self-transcendence dimension.

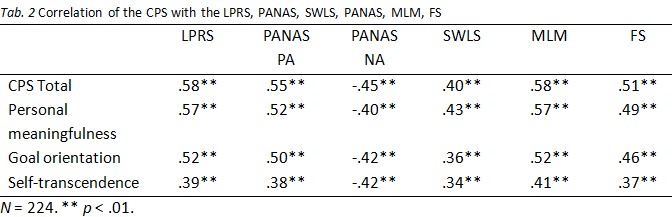

The correlations of the CPS with the LPRS, PANAS, SWLS, PANAS, MLM, FS are reported in Table 2.

Discussion

The aim of the present work was to verify the psychometric properties of the Italian version of the CPS for its use in the Italian context with workers. The dimensionality, reliability and concurrent validity of the instrument were therefore evaluated.

With respect to dimensionality, the Confirmatory Factor Analysis supported the three-dimensional version of the scale in line with the original version (Bronk, Riches, & Mangan, 2018), showing satisfactory statistical model fit indices. Regarding reliability of the scale, the Cronbach alpha coefficients of both the total score and the three dimensions are satisfactory. Concerning concurrent validity of the Italian version of the scale, the positive and significant relationships with the constructs and measures of life project reflexivity, positive affect, life satisfaction, meaning in life, and flourishing support the concurrent validity of the Italian CPS in relation to the respective measures.

From the results of the present study, it is possible to conclude that the Italian version of Claremont Purpose Scale is a valid and reliable instrument for measuring purpose in the Italian context with adult workers.

However, this study presents the limitation of having analyzed the psychometric properties of the Italian version of CPS exclusively with a group of workers from Tuscany who are not representative of the Italian context. Future research should therefore consider groups of participants that are more representative of the Italian reality, including workers from other geographic areas of Italy and also extending to other age groups, such as secondary school students or university students.

Despite the highlighted limitations, the Italian version of the CPS was found to be an instrument capable of the reliable and accurate assessment of purpose. The availability of this scale opens up possibilities for research and intervention in the Italian work context from a positive prevention (Di Fabio & Kenny, 2015, 2016, 2018; Hage et al., 2007; Kenny & Hage, 2009) and strengths-based prevention perspective (Di Fabio & Saklofske, 2019). Concurrent validity demonstrates the association of purpose with reflexivity processes that are integral to the construction of meaningful personal and work lives (Di Fabio & Blustein, 2016) and favor the well-being of individuals and the promotion of healthy organizations and healthy business (Di Fabio, 2017a, 2017b; Di Fabio & Peiró, 2018; Tetrick & Peiró, 2012).

References

Arbuckle, J. L. (2005). AMOS 6.0 user's guide, vol. 541. Chicago, IL: AMOS Development Corporation.

Benson, P. L. (2006). All kids are our kids: What communities must do to raise caring and responsible children and adolescents (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238-246.

Bentler, P. M. (1995). EQS structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software.

Di Fabio, A., & Blustein, D. L. (2016). Editorial. In A. Di Fabio & D. L. Blustein (Eds.), Ebook Research Topic “From Meaning of Working to Meaningful Lives: The Challenges of Expanding Decent Work” in Frontiers in Psychology. Organizational Psychology, 7, 1119. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01119

Boyle, P. A., Barnes, L. L., Buchman, A. S., & Bennett, D. A. (2010). Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(3), 304-310.

Bronk, K. C. (2011). Portraits of purpose: The role of purpose in identity formation. New Directions for Youth Development, 132, 31-44.

Bronk, K. C., & Finch, W. H. (2010). Adolescent characteristics by type of long-term aim in life. Applied Developmental Science, 14(1), 1-10.

Bronk, K. C., Riches, B. R., & Mangan, S. A. (2018). Claremont Purpose Scale: A measure that assesses the three dimensions of purpose among adolescents. Research in Human Development, 15(2), 101-117.

Browne, M. W. (1990). MUTMUM PC: User’s guide. Columbus, OH: Department of Psychology, Ohio State University.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136-162). Newsbury Park, CA: Sage.

Bundick, M. J., Yeager, D. Y., King, P., & Damon, W. (2010). Thriving across the lifespan. In W. F. Overton, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of lifespan human development (pp. 882-923). New York, NY: Wiley.

Byrne, B. M. (1989). A primer of LISREL: Basic applications and programming for confirmatory factor analytic models. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Carmines, E. G., & McIver, J. P. (1981). Analyzing models with unobserved variables. In G. W. Bohrnstedt & E. F. Borgotta (Eds.), Social measurement: Current issues, 80, 65-115. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Damon, W. (2008). Path to purpose: How young people find their calling in life. New York, NY: Free Press.

Damon, W., Menon, J., & Bronk, K. C. (2003). The development of purpose during adolescence. Applied Developmental Science, 7(3), 119-128.

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71-75.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D. W., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143-156.

Di Fabio, A. (2014). Meaningful Life Measure: Primo contributo alla validazione della versione italiana. Counseling Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni, 7, 307-315.

Di Fabio, A. (2016). Flourishing Scale: Primo contributo alla validazione della versione italiana. Counseling. Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni, 9(1). doi: 10.14605/CS911606.

Di Fabio, A. (2017a). Positive Healthy Organizations: Promoting Well-Being, Meaningfulness, and Sustainability in Organizations. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1938. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01938.

Di Fabio, A. (2017b). The Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development for Well-Being in Organizations. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1534. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01534.

Di Fabio, A., & Gori, A. (2016). Measuring adolescent life satisfaction: Psychometric properties of the Satisfaction With Life Scale in a sample of Italian adolescents and young adults. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 34(5), 501-506.

Di Fabio, A., & Kenny, M. E. (2015). The contributions of emotional intelligence and social support for adaptive career progress among Italian youth. Journal of Career Development, 42(1), 48-59.

Di Fabio, A., & Kenny, M. E. (2016). From Decent Work to Decent Lives: Positive Self and Relational Management (PS&RM) in the Twenty-First Century. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 361. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00361.

Di Fabio, A., & Kenny, M. (2018). Intrapreneurial Self-Capital: A Key Resource for Promoting Well-Being in a Shifting Work Landscape [Special Issue]. Sustainability, 10(9), 3035. doi: 10.3390/su10093035.

Di Fabio, A., Maree, J. G., & Kenny, M. E. (2018). Development of the Life Project Reflexivity Scale: A new career intervention inventory. Journal of Career Assessment, 1-13.

Di Fabio, A., & Peiró, J. (2018). Human Capital Sustainability Leadership to Promote Sustainable Development and Healthy Organizations: A New Scale [Special Issue]. Sustainability, 10(7), 2413. doi: 10.3390/su10072413.

Di Fabio, A., & Saklofske, D. H. (2019). Compassion and Self-compassion in organizations: From personality traits to emotional intelligence. In the Symposium organized by A. Di Fabio & D. H. Saklofske (Chairs), Emotional Intelligence: 30 Years Later. Symposium conducted at the International Society for the Study of Individual Differences - ISSID – International Conference, Florence, Italy, July 29 – August 2, 2019.

French, S., & Joseph, S. (1999). Religiosity and its association with happiness, purpose in life, and self-actualisation. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 2(2), 117-120.

Hage, S. M., Romano, J. L., Conyne, R. K., Kenny, M., Matthews, C., Schwartz, J. P., & Waldo, M. (2007). Best practice guidelines on prevention practice, research, training, and social advocacy for psychologists. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(4), 493-566.

Hill, P. L., & Burrow, A. (2012). Viewing purpose through an Eriksonian lens. Identity: an International Journal of Theory and Research, 12(1), 74-91.

Hill, P. L., & Turiano, N. (2014). Purpose in life as a predictor of mortality across adulthood. Psychological Science, 25(7), 1482-1486.

Kenny, M. E., & Hage, S. M. (2009). The next frontier: Prevention as an instrument of social justice. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 30(1), 1-10.

Mariano, J. M., & Vaillant, G. E. (2012). Youth purpose among the ‘greatest generation’. Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(4), 281-293.

Marsh, H. W., & Hocevar, D. (1985). Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First — and higher — order factor models and their invariance across group. Psychological Bulletin, 97(3), 562-582.

Morgan, J., & Farsides, T. (2009). Measuring meaning in life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(2), 197-214.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069-1081.

Ryff, C. D., Singer, B., & Love, G. D. (2004). Positive health: Connecting well-being with biology. Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences, 359, 1383-1394.

Terraciano, A., McCrae, R. R., & Costa Jr, P. T. (2003). Factorial and construct validity of the Italian Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19(2), 131-141.

Tetrick, L. E. & Peiró, J. M. (2012). Occupational Safety and Health. In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Psychology (Vol. 2). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Tucker, L. R., & Lewis, C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38(1), 1-10.

Turner, A. D., Smith, C. E., & Ong, J. (2017). Is purpose in life associated with less sleep disturbance in older adults? Sleep Science and Practice, 1(14). doi: 10.1186/s41606-017-0015-6.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063-1070.

Autore per la corrispondenza

A. Di Fabio. Tel. +39 055 2755013; Fax +39 055 2756134. Indirizzo e-mail: E-mail: adifabio@psico.unifi.it Dipartimento di Formazione, Lingue, Intercultura, Letteratura e Psicologia (Sezione di Psicologia), Università degli Studi di Firenze, via di San Salvi 12 – Complesso di San Salvi, Padiglione 26, 50135, Firenze, Italia.

Note

1 A

© 2017 Edizioni Centro Studi Erickson S.p.A. ISSN 2421-2202. Counseling. Tutti i diritti riservati. Vietata la riproduzione con qualsiasi mezzo effettuata, se non previa autorizzazione dell'Editore.