Introduction

Architecture is the discipline that, combining art and technique, has the purpose of organising space on any scale and therefore mainly of defining the built environment where human beings live, both individually and in groups. In the development of human identity, places are a fundamental element of experience; it is in this context that both psychology of architecture and studies on the relationship between architecture and neuroscience came about. The first discipline provides the scientific basis for the relationship between the characteristics of the environment and the emotional responses of people (De Marco, 2015; Wölfflin, 1946); the second codifies the architectural space that is constituted primarily through an emotional and multisensory experience and is defined by elements which, through their formal and material composition, transmit infinite information to the human eye (Mallgrave, 2015).

It can therefore be shown how the built environment can influence the health and well-being of people and also how the latter are able to perform their vital and professional functions in the various environments in which they live, experiencing different moods.

This paper aims to analyse this field of study, assessing the level of well-being, in terms of both individuals and communities in relation to architectural projects, as well as to show how the project itself can define the conditions that respond to the material and emotional needs of people by relating to the new research area of the psychology of sustainability and sustainable development. Psychology and creativity, in the design phase, have an important value within this research theme; the identity of architecture, with its shapes, building materials, and colours, gives buildings virtues capable of communicating feelings and moods, from emotion to pleasure. In this context, how can the architecture of the past and above all that of the present favour and stimulate the well-being and happiness of a person? This is an age-old question and one that designers could and should ask themselves in order to design and qualify living places.

Identity of the place and identity of the person

Over time, the process of building the identity of a place has become stratified and its importance has contributed to the consolidation of inhabitants’ sense of belonging and recognisability of the context. In this process, the landscape, buildings and all the elements linked to the sphere of life occupy a central role; they are in fact expressions of the local culture, in the context of the economic dynamics and socio-cultural values that have developed and that have conditioned human action. The factors that determine the identity of the place, however, cannot be limited to physical elements, but are recognisable through a broad study of the history of local reality. Looking at the settlements of the territory in these terms therefore means considering them as products that speak of a community that experiences and transforms them, interacting with its own environment of life. A community that, especially in the past, has directly related to the available natural resources and has also dialogued with the harshness and difficulty of a place, shaping its transformations according to these needs; a process that today we can fully frame in the canons of sustainability in its broadest sense, be it environmental, social, economic etc. The ancients understood the importance and complexity of this process to the point that the choice of where to build a new city was entrusted to a figure who had various qualities - a leader, a priest, a philosopher, an architect - and they had to know how to interpret omens, signs, narratives, wholesomeness, geographical elements etc.

Although the expression place is used to indicate a portion of materially delimited space, in reality, the proper meaning of place exceeds pure spatiality and material extension, having its own well-defined character, the so-called genius loci. The genius loci thus survives the evolving functional structures and gives an indelible character to the settlement and also to the landscape (Norberg-Schultz, 1979). In this context, it is clear how the Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development (Di Fabio, 2017a, 2017b, Di Fabio & Rosen, 2018), representing a new area of research in the field of psychology, responds to research that introduces a psychological contribution to the transdisciplinary perspective of the science of sustainability, capable of making a significant contribution to the reading of the genius loci, which is one of the main phases of the architectural project. This innovative psychological perspective broadens the concept of sustainability, also in the field of architecture (Leporelli, Santi, & Di Sivo, 2018; Santi & Leporelli, 2018), overcoming a perspective based exclusively on the ecological and socio-economic environment, and seeks to improve the quality of life of every human being in their environment. Therefore, architecture, with its buildings, its spaces and its places, is one of the main players influencing the well-being of human life, “Architecture is the expression of a time, since it reproduces the physical being of the human, his manner, his motion, his behaviour” (Wölfflin, 1888/1928, pp. 1114-1159).

Architecture is a fact of art, as Le Corbusier (1923) claimed, a phenomenon that arouses emotion, beyond the problems of construction, beyond them; and construction is to keep up: architecture is to move, therefore, architecture evokes sensations and embodies something spiritual representing the image of a community. In fact, looking at a simple iconic scheme of a city, its skyline, we immediately identify it and recognise it in its symbolic buildings, recalling images, memories and sensations experienced in the mind (Figure 1).

The crisis in the contemporary system (Kuhn, 1969), referring to the logic of the scientific process, is generating a change of paradigm that we could summarise as a progressive disappearance of the thresholds between man and architecture, user and work, both perceptually and at a body level.

The emotional and physical involvement of the user of architecture today becomes a need capable of revolutionising the face of cities and triggering economic-productive and settlement processes that are now clearly perceptible in the political and administrative choices linked to major world realities.

At the same time, the loss of the ability to recognise the identity of the place leads to the eradication of the individual, that is the termination of the relationship between man and the environment, resulting in the logic of the implementation of economic power that distorts, destroys and erases the signs of time in the name of feared progress, “buildings as embodying social institutions, their physical exteriors and the effects of the image of these buildings in transmitting – under particular conditions – certain symbolic messages” (King, 2004, p. 16).

Figure 1 – Some of the most important city skylines in the world. We can see how architecture represents a city.

A second consideration that can be made is that if communities identify with the place, and therefore with the city and its architectural symbols, in a biunique relationship where architecture represents the image of the community itself, the loss of an architectural artefact can correspond to the loss of a symbol, causing a great sense of emptiness and loss, with the loss of psychological well-being, “for each image we submit the image of ourselves, we feel that everything must be in the same conditions that we consider necessary for our well-being” (Wölfflin, 2010, p. 18). From here, there are numerous examples, throughout history, of reconstructive processes of rebuilding artefacts lost as a result of collapse or disaster, from reconstructions loyal to com’era dov’era (The famous phrase “where it was and how it was” appears for the first time in an official speech on April the 25th 1903 by the mayor of Venice, Grimani, on the occasion of the ceremony of laying the foundation stone for the reconstruction of Saint Mark’s bell tower. This expression showed the desire, taken for granted in the spirit of the Venetians and initially not pronounced, to see the bell tower rebuilt where it had always been and how it had always been), to urban regeneration with new buildings replacing the previous ones. In the case of the Twin Towers in New York, their collapse following a terrorist attack not only caused the devastation of the buildings but “more than 50,000 people participated in the rescue and recovery work that followed the Sep the 11th 2001 (9/11) attacks on the World Trade Center (WTC). Multiple health problems in these workers were reported in the early years after the disaster. We report incidence and prevalence rates of physical and mental health disorders during the 9 years since the attacks, examine their associations with occupational exposures, and quantify physical and mental health comorbidities” (Wisnivesky et al., 2011).

Throughout history, architecture has been an instrument of affirmation of the various forms of power and government, and architectural language has become an important part of the claimed logic of collective identity. It should also be pointed out that the construction sector is one of the sectors most responsible for the destruction and degradation of natural resources, the production and accumulation of waste and environmental impact. This is why there is a need for sustainable development in a broad sense: be it environmental, economic or social. In this context, the psychology of sustainability and sustainable development (Di Fabio, 2017a; 2017b; Di Fabio & Rosen, 2018) sees sustainability not only from an ecological and socio-economic perspective (Brundtland Report, 1987) but also in terms of improving the quality of life of every human being and of their environment. One of the tasks of designers is therefore the possibility to plan and design architectural spaces whilst focusing on the wellbeing of users in the environment, taking into account the theme of sustainability with a transdisciplinary interpretation in its new perspective of the Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development.

Proposing reflections for the definition of design guidelines

That described above is the complex relational system between the identity of the individual and the identity of a place, with the latter being understood in an environmental and anthropised dimension, in which the close relationship between architecture and its perception on the part of the human being emerges. It is in this context that the processes of space transformation operate, through projects both on an urban and an architectural scale, and it is in the planning phase that one can act in order to direct the design process, by its very complex nature, towards an awareness of human beings’ wellbeing, from the perspective of the Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development. It is therefore necessary to identify design strategies that can be followed by designers.

The research work developed, a brief summary of which is illustrated in this paper, has elaborated the first guidelines for architectural design, both on an urban scale and on the scale of a single building, based on best practice case studies (City of New York, 2010; Santi, 2015), which integrate general principles referring to the psychology of sustainability and sustainable development. These prevention guidelines are designed to be ambitious and, therefore, to promote a high level of professional practice by designers, both at the level of interventions that affect individuals and communities (Santi & Leporelli, 2018). The guidelines are intended to be non-mandatory and non-exhaustive as they may not be applicable to all project conditions and situations. It must also be noted that they are not definitive and do not intend to replace the creative phase and discretion of designers. To date, these guidelines represent an initial effort to provide a guiding tool to encourage best practices for designers.

The specific objectives of these guidelines to incentivise best practices are to provide:

(a) a framework for active prevention for people, citizens and communities, in terms of health and well-being;

(b) a motivation to address the theme of well-being at the level of the individual as a whole, in the design of architectural spaces;

(c) information, relevant terminology and current research, providing operational support for the designer;

(d) a set of principles to improve the liveability of architectural spaces.

The promotion of the movement of human beings, both in the open air, with the design of neighbourhoods, roads and open spaces that favour soft mobility, and with the construction of active buildings that stimulate people's physical activity (Johnson & Marko, 2007; Lee & Vernez Moudon, 2004), has been identified as a determining principle for encouraging active prevention. To allow this, in the design of public spaces, measures to be taken focus on the design of accessible pedestrian streets with high connectivity, traffic reduction, attention to the landscape, lighting, rest areas and the presence of water and fountains, but also on the development of continuous cycle networks. An active design then, which is also of considerable importance not only for public health but also for the environment in terms of sustainability; in fact, a design with these assumptions promotes physical activities, such as walking instead of driving or the use of stairs instead of elevators, and outdoor activities. All practices that, in a world fighting against pollution damage, can contribute to the reduction of emissions of harmful gases caused by means of transport and energy consumption, within a vision of sustainable development (United Nations, 2015).

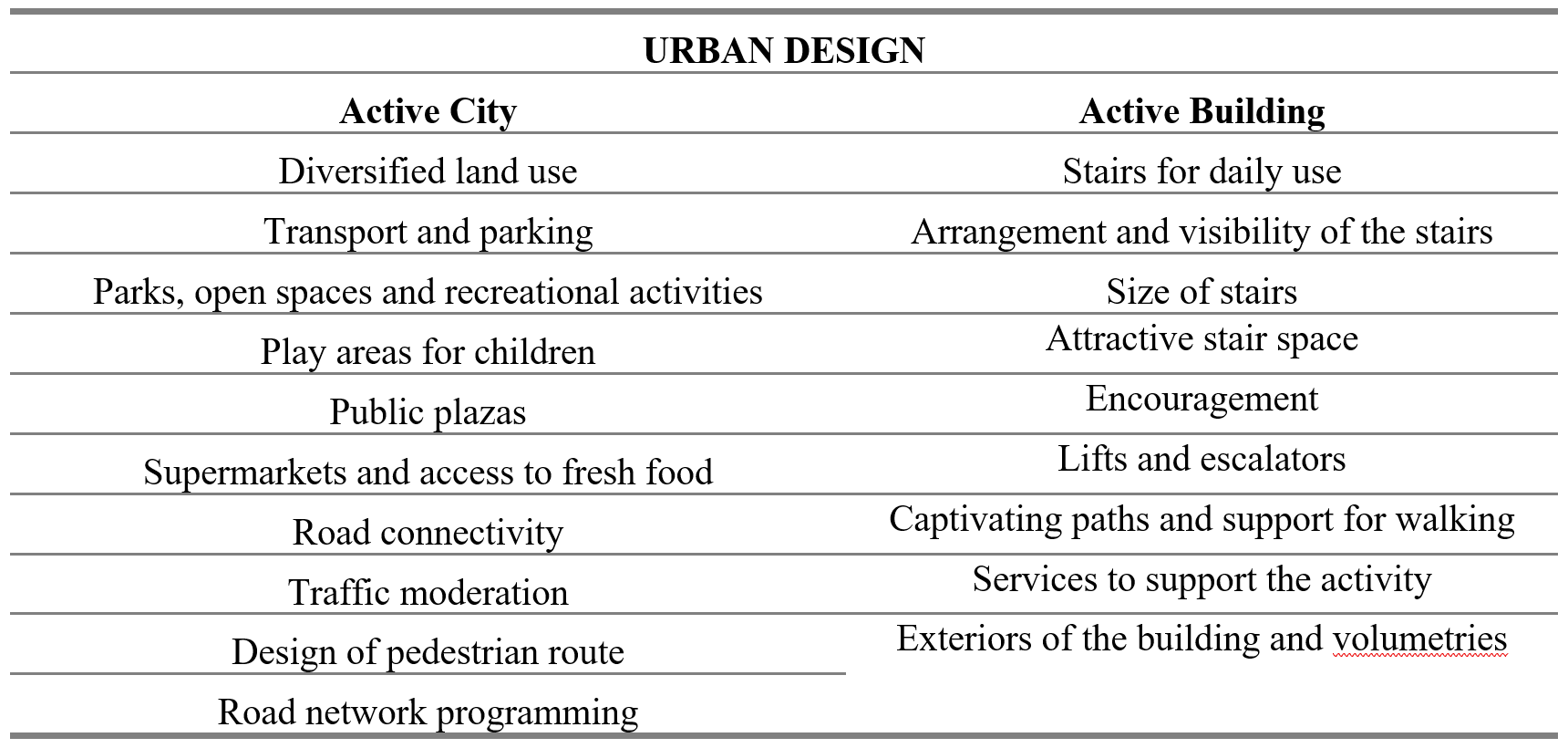

In addition, variables that are fundamental for the analysis of the relationship between urban and architectural design and mobility models have been taken into account; these are identified in density (such as the concentration of jobs and people in a given urban area or space), in diversity (the number, variety and balance of land use in the territory or functions in a space) and in design (the characteristics of the road and street network of a district, or of the distribution spaces of a building) (Cervero & Kockelman, 1997; Leporelli & Santi, 2018; Santi, 2015). They can be furthermore identified in destination (the ease of reaching a central business district or another concentrated area of jobs and attractions) and in distance (measuring the average distance from home or work to the nearest train station or bus stop). Thanks to these indicators it was possible to summarise the basic principles of an active city and an active building.

Subsequently, the main design recommendations were drafted and these included a series of indicators to be verified on an urban scale (development and maintenance of mixed land use in city neighbourhoods; improvement of access to squares, parks, open spaces, and recreational facilities, and the design of these spaces to maximise their active use; improved access to a full array of food stores and fresh products; design of accessible pedestrian streets with high connectivity; measures to reduce traffic; landscaping; lighting; benches; water and fountains; facilitating the use of bicycles for recreational activities and transport through the development of continuous cycle networks and integrating secure parking infrastructures for outdoor and indoor bicycles) and on an architectural scale (creating environments that stimulate active life, planimetric and volumetric development that encourages non-mechanised mobility, environments that stimulate psycho-physical well-being and internal comfort, services to support internal functions, and attractiveness of external spaces) (Table 1).

The aim of the project is to promote planning activity that is increasingly oriented towards spaces and structures envisaged in terms of the psychic and physical wellbeing of the user and which provide possibility and opportunities for movement for the individual. In this context, it is possible to obtain a transformation of the built environment according to sustainability focused on hedonic well-being (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) and eudemonic well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2001; Waterman et al., 2010).

In this framework, it is possible to go beyond the traditional borders understood as thresholds dividing one space from another, the inside from the outside, the private from the public; we think of dynamic boundaries that are not limited to dividing two entities but react to human activity and may even require its interference to be activated. From this point of view, "designing wellbeing" (Santi, 2015) defines a new way of thinking and perceiving both public space and architecture, making them both active in improving the quality of life of human beings.

Table 1 – Synthesis diagram of the main issues that affect design for well-being.

Conclusions

If personal identity is constructed in social interaction thanks to language and not, looking for a supposed interiority in itself, there is also a collective identity that is changing too, and which crosses personal identities by indissolubly linking them together. In this context, the relationship between the identity of the individual and the identity of a place is very complex. Each generation has dreamed of a reality different from the one actually experienced and has modified a physical space more or less incisively. The latter is therefore the realisation, successful or otherwise, of the dreams of sequentially different communities that over time have alternated, confused and hybridised. Each generation, with all its contaminations, with different cultures and customs, has tried to design an adequate inhabitation of the world, and each of them has had to deal with a reality resulting from the dreams of the past, of their own and of others. This is why the identity of a place, especially with its architecture, is the result of multiple projects of life and environment of past generations, from which architecture, therefore, evokes sensations embodying spiritual values and representing the image of a community capable of communicating feelings and moods, from emotion to pleasure, in human beings. “Architecture is really about well-being. I think that people want to feel good in a space ... It is about to become more popular in public and it's about people enjoying that space. That makes life that much better. If you think of housing, education, of schools and hospitals, these are all very interesting projects because of the way you interpret this special experience” (Hadid, 2016). Our hope is that these evolving guidelines are an incentive for designers to evaluate their preparation, to engage in prevention work and to promote their education and training by increasing their knowledge, skills and experience in the field of individual well-being and community well being, also taking into account the principles of the psychology of sustainability and sustainable development (Di Fabio, 2017a; 2017b; Di Fabio & Rosen, 2018).

References

Brundtland Report (1987). Our Common Future. New York, NY: Butterworth.

Cervero, R., & Kockelman, K. (1997). Travel demand and the 3Ds: Density, diversity, and design. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 2, 199-219. doi: 10.1016/S1361-9209(97)00009-6

City of New York (2010). Active design guidelines, promoting physical activity and health in design. Available at: http://centerforactivedesign.org/dl/guidelines.pdf

De Marco, S. M. (2015). Psicologia e architettura: Studio multidisciplinare dell’ambiente. Villanova di Guidonia: Aletti.

Di Fabio, A. (2017a). Positive Healthy Organizations: Promoting well-being, meaningfulness, and sustainability in organizations. In G. Arcangeli, G. Giorgi, N. Mucci, J.-L. Bernaud, & A. Di Fabio (Eds.), Emerging and re-emerging organizational features, work transitions and occupational risk factors: The good, the bad, the right. An interdisciplinary perspective. Research Topic in Frontiers in Psychology. Organizational Psychology, 8, 1938. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01938

Di Fabio, A. (2017b). The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. In G. Arcangeli, G. Giorgi, N. Mucci, J.-L. Bernaud, & A. Di Fabio (Eds.), Emerging and re-emerging organizational features, work transitions and occupational risk factors: The good, the bad, the right. An interdisciplinary perspective. Research Topic in Frontiers in Psychology. Organizational Psychology, 8, 1534. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01534

Di Fabio, A., & Rosen, M. A. (2018). Opening the Black Box of Psychological Processes in the Science of Sustainable Development: A New Frontier. European Journal of Sustainable Development Research, 2(4), 47. https://doi.org/10.20897/ejosdr/3933

Hadid, Z. (2016). Lecture in RIBA Gold Medal, in 2016, to explain how architecture must contribute to society’s progress and ultimately to our individual and collective well-being. Zaha Hadid was the first woman Architect to win the Gold Medal.

Johnson, S., & Marko J. (2007). Designing healty places. Land use plannig and public health. Edmonton, Alberta:

Population Health-Capital Health.

King, A. (2004). Spaces of global cultures. Architecture, urbanism, identity. London: Routledge.

Kuhn, T. (1969). La struttura delle rivoluzioni scientifiche. Torino: Einaudi.

Le Corbusier (1986). Verso una Architettura. Milano: Longanesi. (Original version published in 1923).

Lee, C., & Vernez Moudon, A. (2004) Physical activity and environment research in the health field: Implications for urban and transportation planning practice and research. Journal of Planning Litterature, 1, 147-168. doi:10.1177/0885412204267680.

Leporelli, E., & Santi, G. (2018, September). From healthy perspective in the rehabilitation of architectural heritage to decent and sustainable development. Invited lecture in the One-Day International Conference “Decent work and sustainable development: the perspective of existential psychology for innovation and social inclusion.” Università degli Studi di Firenze, UNESCO, Uniwersytet Wroclawski, Comune di Firenze. Florence, Italy, 21 September 2018.

Leporelli, E., Santi, G., & Di Sivo, M. (2018). Health, well-being and sustainable built environment: From the new research area of the psychology of sustainability and sustainable development to innovation in architectural research. Counseling. Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni, 11(3), doi 10.14605/CS1131803.

Mallgrave, H. F. (2015). L’empatia degli spazi. Architettura e neuroscienze. Milano: Raffaello Cortina.

Norberg-Schultz, C. (1979). Genius loci. Milano: Electa.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). To be happy or to be self-fulfilled: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141-166.

Santi, G. (2015). Progettare per il benessere. In V. Cutini & G. Santi, G. (Eds.), Una città in movimento. Architettura, spazio urbano e mobilità a Pisa (pp. 64-99). Pisa: Pacini.

Santi, G., & Leporelli, E. (2018). La sostenibilità degli spazi urbani per healthier societies. Counseling. Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni, 11(3), doi 10.14605/CS1131806

United Nations (2015). Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable- development- goals/ (consulted on 18th February 2019).

Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Ravert, R. D., Williams, M. K., Bede Agocha, V., et al. (2010). The Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being: Psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 41-61.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063-1070.

Wisnivesky, J. P., Teitelbaum, S. L., Todd, A. C., Boffetta, P., Crane, M., Crowley, L., et al. (2011). Persistence of multiple illnesses in World Trade Center rescue and recovery workers: A cohort study. The Lancet, 378, 888-897.

Wölfflin, H. (1888). Rinascimento e Barocco. Firenze: Sansoni. (Original version published 1888).

Wölfflin, H. (1946). Prolegomena zu einer. Psycologie der Architektur. Basel: Schwabe AG Verlag.

Wölfflin H. (2010). La psicologia dell’architettura: Milano: Edizioni Et al.