Vol. 13, n. 1, febbraio 2020

INVITED ARTICLES

Life Project Reflexivity Scale in Greek University Students

Katerina Argyropoulou1, Stamatis-Alexandros Antoniou2, Nikolaos Mouratoglou3,Argyro Charokopaki4 and Katerina Mikedaki5

Abstract

The Life Project Reflexivity Scale (LPRS) is a 15-item scale intended to evaluate individuals’ reflexivity regarding future career–personal–life projects. LPRS is a multidimensional construct composed of three specific dimensions: Authenticity, Acquiescence and Clarity/Projectuality. The aim of the study was to determine the factor structure and psychometric properties of the Greek LPRS. The instrument was administered to 183 university students in Athens, Greece. Confirmatory factor analyses were performed to assess the latent structure of the Greek LPRS. The final indices of Goodness of Fit showed satisfactory fit to the data. The Cronbach’s alpha of the Greek LPRS is .75. The Greek LPRS correlates with the Meaningful Life Measure and the Authenticity Scale, thus showing adequate concurrent validity evidence.

Keywords

Reflexivity, multidimensional construct, higher education, career counselling, vocational guidance.

ARTICOLI SU INVITO

Life Project Reflexivity Scale in studenti universitari greci

Katerina Argyropoulou6, Stamatis-Alexandros Antoniou7,Nikolaos Mouratoglou8,Argyro Charokopaki9 e Katerina Mikedaki10

Sommario

La Life Project Reflexivity Scale (LPRS) è composta da 15 item e intende rilevare la riflessività degli individui sui progetti futuri di carriera e di vita. La LPRS è un costrutto multidimensionale con tre specifiche dimensioni: Authenticity, Acquiescence, Clarity/Projectuality. Lo scopo dello studio è di determinare la struttura fattoriale e le proprietà psicometriche della versione greca della LPRS. Lo strumento è stato somministrato a 183 studenti universitari di Atene, Grecia. Sono state effettuate analisi fattoriali confermative per valutare la struttura latente della scala. Gli indici di Goodness of Fit mostrano un soddisfacente fit ai dati. L’alfa di Cronbach è .75. La versione greca della LPRS correla con la Meaningful Life Measure e con l’Authenticity Scale, mostrando un’adeguata validità concorrente.

Parole chiave

Riflessività, costrutto multidimensionale, higher education, career counseling, vocational guidance.

Introduction

The 21st century is characterized by continuous change in the world of work as well as in other life domains. Strong demographic changes, massive migration flows, and rapid technological advancements have created multiple challenges regarding individuals’ career development and well-being, especially for those who face uncertainty and instability in their work lives (Stoddard, Zimmerman, & Bauermeister, 2011). According to Duarte (as cited in Kassotakis, 2014) careers are no longer related to an organization, but increasingly belong to the people, while Di Fabio (2014b) suggests that «while in the 20th century workers developed careers within stable organizations, in the 21st century, organizations are more fluid» (p. 193).

With respect to the local Greek context, the often-bewildering changes in the world of work lead to the increase of uncertainty among young people along with fatalistic attitudes towards unemployment (Mylonas et al., 2016). Unlike earlier generations, young Greeks face an uncertain future (and career prospects); in order to achieve success in the 21st century, they need to take ownership of actively managing their careers and balancing their lives (Sidiropoulou-Dimakakou, Mikedaki, Argyropoulou, & Kaliris, 2018). They need to develop not only the characteristics required to face globalization and cope with an unpredictable and challenging work-life environment, but they also need to identify meaningful life projects characterized by clarity to advance their personal and professional lives (Di Fabio & Kenny, 2016). In addition, Savickas (2011) suggests that greater flexibility, personal adaptability, intentionality, and lifelong learning could help individuals to maintain high levels of employability and openness to change. Moreover, Guichard (2009) emphasizes the adoption of a balanced approach between two kinds of reflexivity related to commitment and psychological flexibility respectively. These assumptions are associated with Di Fabio (2014a), who proposes the development of responsibility in personal and professional career-life trajectories in order to achieve a successful life and Guichard (2016) who suggests that counseling interventions should assist people in coping with this responsibility.

As far as practitioners are concerned, career counselors need to reflect critically on their theory and practice in order to support people in constructing their career and life projects (Di Fabio & Maree, 2016). The emergence of reflexivity, as an important intervention tool grounded on narrative and biographical approaches, enables career counselors to facilitate clients’ capacity to define who and what they want to become in their work and in their lives by and large (Di Fabio, 2017; Savickas, 2013). Therefore, career counselors need to adopt such interventions that focus on enabling individuals to take a reflexive stance on their experiences and develop their self-determination abilities (Guichard, Pouyaud, De Calan, & Dumora, 2012). Reflexivity as an active and continuous process (reflecting on and taking the steps needed to promote current and future projects) emphasizes the importance of personal meaning in personal and professional projects, strengthens the authentic aspects and values of the Self in the context of an uncertain and shifting work landscape, and thereby, contributes to life-career projects that ultimately promote well-being. Furthermore, advanced counseling interventions can enhance client’s life project reflexivity profile (Di Fabio, Maree, & Kenny, 2018) in order to support sustainable career-life projects and inspire successful actions and positive change (Maree & Di Fabio, 2015).

In this context, Di Fabio, Maree and Kenny (2018) proposed the Life Project Reflexivity Scale (LPRS) as a multidimensional construct composed of three specific dimensions that are generally aligned with the tenets of life and identity construction theory (Guichard, 2005, 2013); namely Authenticity, Acquiescence and Clarity/Projectuality. Authenticity refers to individual’s awareness on their future career-personal-life projects as a basis of the authentic values and the meaning that is aligned with those values. The Clarity/Projectuality dimension refers to individual’s clarity about their career-personal-life projects and assesses whether they know what they want to become in their next life chapters. The Acquiescence dimension reveals a sense of conforming to and passively accepting values imposed on people by their society rather than basing the career-life projects on one’s authentic values.

Against the backdrop of a rapidly changing world of work and the need to enable the Greek youth to clarify and strengthen their reflexivity, the authors set out to adapt and validate the Life Project Reflexivity Scale (LPRS) in the Greek context. In order to develop interventions to improve clients’ reflexivity, it would be necessary to establish a scale of measurement that is locally validated. Validating LPRS in the Greek population would be essential in order to enable career counselors to assist individuals in terms of achieving their full potential and to give meaning to their future life projects (Converso, Sottimano, Molinengo, & Loera, 2019). Moreover, the present study provides an additional psychometric evidence for the LPRS beyond the original group of Italian participants on which it was tested. In the study of the original version of the LPRS positive relationships emerged with psychological variables (Authenticity and Meaningful Life), important variables for career and life construction in the 21st century.

Aims of the Study

The primary aim of this study was to explore the suitability of the Life Project Reflexivity Scale (Di Fabio, Maree, & Kenny, 2018) to a population of Greek university students, taking into account the precarious state of both the economy and the labour market in Greece. For this reason, the authors tested the three-factor structure of LPRS, including 15 items, through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). In addition, the authors examined LPRS’s construct validity by comparing student groups that would be theoretically expected to differ in their scores (Anastasi & Urbina, 1997). Comparisons between groups were performed based on gender as the processes of career planning are differentiated (Patton, Bartrum, & Creed, 2004). In addition, Di Fabio, Maree and Kenny (2018) conclude that males have clearer future goals (increased clarity), however they tend to be more influenced by social values, in comparison with females (increased acquiescence). Furthermore, comparisons between groups were performed based on the university studies’ level, as students tend to differentiate their perceptions in relation to various aspects of their career planning (indicatively: employers’ attractiveness, Arachchige & Robertson, 2013; perceived benefits of social networks for career management, Benson, Filippaios, & Morgan, 2009; and online networking for career planning, Benson, Filippaios, & Morgan, 2010).

Method

Participants

In this study, 183 university students participated, attending a degree in the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. There were 73 males (39.90%) and 110 females (60.10%), while the mean age was 25.95 (SD = 6.94). Students were attending either an undergraduate programme (62.30%), or a postgraduate programme (37.70%). It must be noted that the duration of Bachelor’s degrees in Greece is at least four years, with some exceptions such as Engineering that can be completed in at least five years.

Measures

Life Project Reflexivity Scale. LPRS consists of 15-items with a response format on a five-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The scale has three dimensions: Clarity/Projectuality (example of item: «The projects for my future life are clearly defined»); Authenticity (example of item: «The projects for my future life are full of meaning for me»); Acquiescence (example of item: «The projects for my future life are more anchored by the values of the society in which I live than my most authentic values»). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the original Italian version for the three dimensions of LPRS were Authenticity (.86), Acquiescence (.83), Clarity/Projectuality (.89), and LPRS total (.86).

Authenticity Scale. To measure authenticity, the authors used the Authenticity Scale (AS) that Wood and his colleagues’ developed (Wood et al., 2008). The questionnaire comprises 12 items (e.g., «I feel out of touch with the real me», «I stay true to myself in most situations», «I always feel I need to do what others expect of me») aimed at measuring individual’s authenticity by a 7-point Likert-type rating scale anchored by 1 = «does not describe me at all» and 7 = «describes me very well. These 12 items are divided into three dimensions that measure authenticity of Self-alienation, Authentic living and, Accepting external influence. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the Greek version were .81 (total scale), .70 (Self-alienation), .64 (Authentic living), and .86 (Accepting external influences).

Meaningful Life Measure. The Meaningful Life Measure (MLM) derived from Morgan and Farsides (2009) was also employed, composed of 23 items (e.g., «Life to me seems always exciting», «So far, I am pleased with what I have achieved in life», «I have a personal value system that makes my life worthwhile», «I have a clear idea of what my future goals and aims are», and «My life is significant»). These 23 items are divided into five dimensions, namely, Exciting life, Accomplished life, Principled life, Purposeful life, and Valued life. Participants report the degree to which they possess each dimension of meaningful life on a 7-point Likert rating scale anchored by 1 = «strongly disagree» and 7 = «strongly agree» for each of the 23 items. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the Greek version were .84 (total scale), .50 (Exciting life), .75 (Accomplished life), .88 (Principled life), .60 (Purposeful life), and .90 (Valued life).

A one-page demographic questionnaire was also used to collect information on participants’ background information.

Procedure

The survey lasted approximately three months. Students’ participation was voluntary and without compensation. Informed written consent was acquired before the administration of the questionnaires, while confidentiality of the data was maintained throughout all the research stages. The standard procedure of back translation was followed (van de Vijver & Leung, 1997). The instruments of the survey were translated into Greek, by the third author and were revised by the first and second author. Also, back translations were carried out by a qualified native English translator. Questionnaires were administered by the fifth author, a qualified and trained psychologist, at the end of university lectures in the course «Career Guidance and Career Decision Making», of the Department of Educational Studies. Each questionnaire was screened by the third author in order to guarantee that there were no missing data. The research adhered to the ethical requirements stipulated in the Code of Conduct for responsible research issued by WHO.

Data Analysis

The factorial structure of the Greek Life Project Reflexivity Scale (LPRS) was tested using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with AMOS (maximum likelihood method). The confirmatory analysis was carried out to confirm the multidimensional construct composed of three specific dimensions: Authenticity, Acquiescence and Clarity/Projectuality, for the Greek version. The first order dimensions are the following: 1) Authenticity, 2) Acquiescence and 3) Clarity/Projectuality.

Different indices were used to estimate the fit of empirical data to the theoretical model: the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and the Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR). For the TLI (Bentler & Bonett, 1980; Hu & Bentler, 1999) and CFI (Bentler & Bonett, 1980), values of almost 0.90 are indicators of a good fit. Values of the RMSEA and SRMR less than .08 indicate a good fit (Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Móller, 2003; Steiger,1990). The reliability of Greek Life Project Reflexivity Scale (LPRS) was verified using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

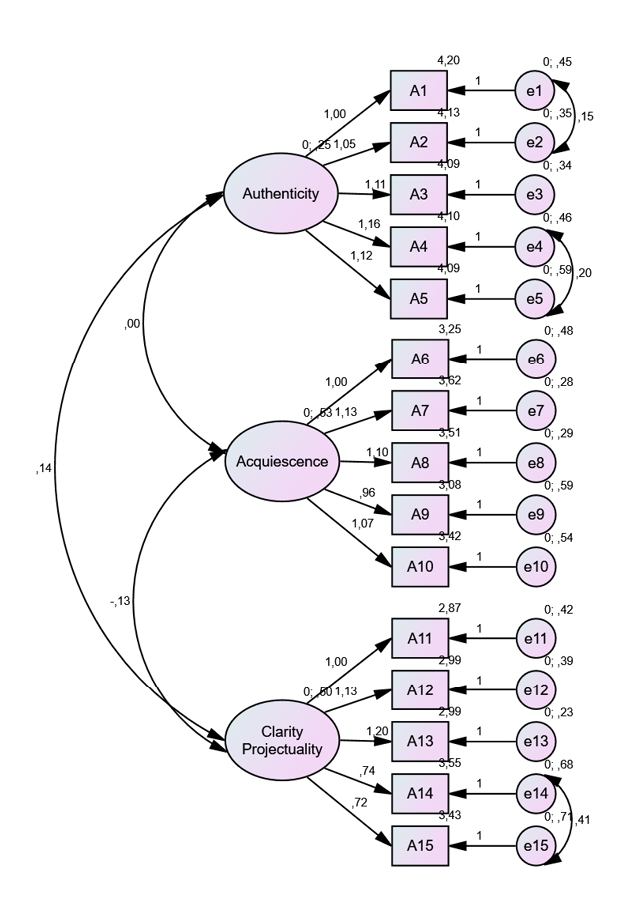

Confirmatory Factor Analysis confirmed the multidimensional construct of the Life Project Reflexivity Scale (LPRS) composed of three specific dimensions: Authenticity, Acquiescence and Clarity/Projectuality (Di Fabio, Maree, & Kenny, 2018). Based on modification indices analysis, an opportunity emerges to add some co-variances. The following three co-variances between the errors were inserted: error of item 14 with error of item 15; error of item 4 with error of item 5; error of item 1 with error of item 2. The final indices of Goodness of Fit are reported in Table 1 and they are satisfactory. The model is presented in figure 1.

Table 1

Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Goodness of Fit (N = 183)

|

TLI |

CFI |

RMSEA |

SRMR |

|

|

LPRS |

0.87 |

0.89 |

0.09 |

0.07 |

Figure 1

Structural model of the Greek Life Project Reflexivity Scale (LPRS).

Reliability estimates

Reliability analysis (internal consistency) for the Greek LPRS was employed and Cronbach’s α was satisfactory both for the total scale (α = .75) and for the subscales (Authenticity: α = .80, Acquiescence: α = .87 and Clarity/Projectuality: α = .83). The above reliability estimates closely match those of the original Italian version of LPRS (Di Fabio, Maree, & Kenny, 2018).

Table 2

Items, means, standard deviations total-item correlations and Cronbach α

|

Items |

M |

SD |

α |

|

1st factor: Authenticity |

.80 |

||

|

A1 |

4.20 |

.83 |

|

|

A2 |

4.13 |

.79 |

|

|

A3 |

4.09 |

.81 |

|

|

A4 |

4.10 |

.89 |

|

|

A5 |

4.09 |

.95 |

|

|

2nd factor: Acquiescence |

.87 |

||

|

A6 |

3.25 |

1.00 |

|

|

A7 |

3.62 |

.97 |

|

|

A8 |

3.51 |

.97 |

|

|

A9 |

3.08 |

1.04 |

|

|

A10 |

3.42 |

1.07 |

|

|

3rd factor: Clarity/Projectuality |

.83 |

||

|

A11 |

2.87 |

.96 |

|

|

A12 |

2.99 |

1.01 |

|

|

A13 |

2.99 |

.97 |

|

|

A14 |

3.55 |

.98 |

|

|

A15 |

3.43 |

.98 |

Gender and LPRS dimensions

To find out whether Greek LPRS scores differed significantly between male and female students of the sample, two-tailed t test comparisons were applied. The results of the comparisons shown in table 3, indicate that the differences in the mean scores of male and female students are not statistically significant in relation to the three dimensions of LPRS; namely, Authenticity, Acquiescence and Clarity/Projectuality.

Table 3

Two-tailed t Test Comparisons Between the Male (N = 73) and the Female (N = 110) Groups on the Life Project Reflexivity Scale (LPRS)

|

LPRS Dimensions |

Male/Female |

M |

SD |

t |

p |

|

Authenticity |

Male |

4.17 |

.57 |

.82 |

> .05 |

|

Female |

4.09 |

.68 |

|||

|

Acquiescence |

Male |

3.34 |

.90 |

-.36 |

> .05 |

|

Female |

3.39 |

.77 |

|||

|

Clarity/Projectuality |

Male |

3.15 |

.72 |

-.22 |

> .05 |

|

Female |

3.17 |

.79 |

Level of university studies and LPRS dimensions

In order to examine whether Greek LPRS scores differed significantly between undergraduate (Bachelor) and postgraduate (Master) students, two-tailed t test comparisons were applied. The results of the comparisons are shown in table 4. No statistical significance was found among university level of studies and the LPRS factors of Authenticity and Acquiescence. However, there is a statistically significant difference (p = .00, p <. 05) between the university level of studies and the LPRS dimension of Clarity/Projectuality. Specifically, undergraduate students have a higher mean score in comparison with the postgraduate students, indicating that they have more clarity in their future goals (M-undergraduates = 3.37, M-postgraduates = 2.82, t(181) = 4.92, p < .01).

Table 4

Two-tailed t Test Comparisons Between the Bachelor (N = 114) and the Master (N = 69) Groups on the Life Project Reflexivity Scale (LPRS)

|

LPRS Dimensions |

Under/Post-graduates |

M |

SD |

t |

p |

|

Authenticity |

Undergraduates |

4.19 |

.58 |

1.80 |

> .05 |

|

Postgraduates |

4.01 |

.71 |

|||

|

Acquiescence |

Undergraduates |

3.33 |

.83 |

-.91 |

> .05 |

|

Postgraduates |

3.44 |

.81 |

|||

|

Clarity/Projectuality |

Undergraduates |

3.37 |

.73 |

4.92 |

< .01 |

|

Postgraduates |

2.82 |

.69 |

Correlations between LPRS, AS and MLM

Pearson’s two-tailed correlations between the Greek LPRS and its three dimensions, as well as the ML and the AU are presented in the following table. All three LPRS dimensions were associated with the LPRS total. The Authenticity dimension was positively associated with all scores, apart from the Acquiescence dimension. The Acquiescence dimension was negatively associated with the Clarity/Projectuality dimension, but not with the Authenticity dimension of LPRS or the MLM and the AS. Finally, the Authenticity and Clarity/Projectuality dimensions of LPRS, along with the total LPRS score were significantly associated with the AS and MLM.

Table 5

Pearson’s two-tailed correlations between the Greek LPRS and its three dimensionsDiscussion

|

Measure |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1. Authenticity |

1 |

|||||

|

2. Acquiescence |

-.02 |

1 |

||||

|

3. Clarity/Projectuality |

.38** |

-.16* |

1 |

|||

|

4. LPRS (total) |

.68** |

.51** |

.65** |

1 |

||

|

5. MLM (total) |

.44** |

.02 |

.39** |

.44** |

1 |

|

|

6. AS (total) |

.21** |

.06 |

.26** |

.28** |

.42** |

1 |

|

**. Correlation is significant at the .01 level (2-tailed). *. Correlation is significant at the .05 level (2-tailed). |

||||||

This study was carried out to explore the suitability of the Life Project Reflexivity Scale (Di Fabio, Maree, & Kenny, 2018) to the Greek context by adapting the LPRS to a population of Greek university students. Data from undergraduate students shows that the validity of Greek LPRS is supported by evidence from CFA (the data fits the original factor structure) and the external validation (correlation with similar constructs). Although the LPRS factorial structure shows satisfactory fit indices for the final model, the 14th item and 15th item for the dimension of Clarity/Projectuality, the 1st item and 2nd item for Authenticity, 4th item and 5th item for the same dimension (Authenticity), seem to be affected from the same factors (as can be seen from the item saturations in figure 1). The main goal of this research was to explore the suitability of LPRS for the Greek context. The three-factorial structure of the scale was confirmed while the five-items per dimension were maintained as well. Results revealed that LPRS-Greek version could be applied safely to a population of Greek university students. Therefore, according to Di Fabio, Maree and Kenny (2018) as well as the confirmatory factor analysis carried out by the authors of the present article, LPRS is a multidimensional construct composed of three specific dimensions: Authenticity, Acquiescence and Clarity/Projectuality. This is a finding which expands the cross-national measurement equivalence of this scale. In addition, the internal consistency estimates were adequate and similar to those of the original Italian version of LPRS (Di Fabio, Maree, & Kenny, 2018). Linguistic explication was as accurate as possible and resembled that of the initial international version in order to avoid misinterpretation.

A significant positive relationship of the total LPRS with the Authenticity Scale (AS) (r = .44, p < .01) and the Meaningful Life Measure (MLM) (r = .28, p < .01) was confirmed offering evidence of construct validity. Furthermore, statistically significant positive correlations were found between the Authenticity subscale of the LPRS with both the MLM and the AS (r = .44, p < .01, r = .21, p < .01). In accordance with this result, these strong correlations confirm the suggestion of Di Fabio, Maree and Kenny (2018) that life project reflexivity combines authenticity and meaningfulness, as well as that authenticity and meaning are interrelated.

The Acquiescence subscale of the LPRS was positively associated with LPRS total, but negatively associated with the Clarity/Projectuality subscale (r = -.16, p < .01), suggesting that the choice of a career-life project that is aligned with societal values cannot be based on clarity and an overall reflective stance. This finding is not in line with the conclusion that Di Fabio, Maree and Kenny (2018) reached, in which Acquiescence and Clarity were positively associated. However, an interpretation of this finding would be that the Greek context (changes in labour legislation and policy, fluid employability, unstable socio-economic conditions) creates differentiations in the societal values and demands. This appears to be reflected in the differences concerning the clarity levels of individuals. The Acquiescence subscale was also negatively associated with the Authenticity subscale, yet, with not statistically significant correlation (r = -.02, p > .05). It should be taken into account that the LPRS items that loaded on the Acquiescence factor include those that describe the prioritization of societal values over authentic values (e.g., «My personal project is more anchored by the values of the society in which I live than my most authentic values»), but also items that do not specify the prioritization of societal values (e.g., «My personal project is anchored by the values of the society in which I live»). Nevertheless, further research is needed to understand the contribution of the acquiescence subscale to life project reflexivity research and practice.

In respect of gender comparisons, no statistically significant differences were found between males and females in relation to the three factors of LPRS. This finding stands in contrast with the conclusion reached by Di Fabio, Maree and Kenny (2018) who support that men had a clearer sense of their future in terms of their career and life projects, while women tend to draw on their authentic needs when devising career-life projects. This result can be interpreted by the fact that clarity and comprehension of career-personal projects are not associated with gender, rather with personal self-regulation sources (Mikedaki, 2015). The lack of statistically significant differences can probably be explained by the similar living conditions of men and women in the Greek context; namely, they have a daily routine that has several common characteristics, act within the same socio-political context, at the same time, elements that form a similar approach in managing their career projects. A potential interpretation of this finding should be sought both in individuals (personality traits) and in cultural elements linked with the general attitude of the Greeks towards career-related issues (Karavia, 2015).

Comparing the LPRS mean scores of undergraduate and postgraduate students, a statistically significant difference was found. Namely, the undergraduate students reported higher scores at the Clarity/Projectuality subscale than Bachelor students, a result contributing to the construct validity argument of LPRS. In the current context, the statistical significance between the level of university studies and Clarity/Projectuality is probably grounded on the fact that a high percentage of students who complete their undergraduate studies, moves on to postgraduate studies. In specific, the Centre of Educational Policy Development (KANEP) of GSEE (Greek General Confederation of Labour), published a report in 2014 stating that the percentage of those studying in a postgraduate course has risen by 162.6 % during the period of 2002-2012. This evidence increases the significance of our interpretation, especially, if we take into account that during 2009-2012, Greece was facing the consequences of the financial crisis. In addition, this is in line with OECD’s (2018) report, which states that individuals with a master’s degree increase their possibility of finding a job. Therefore, an interpretation of this finding is that undergraduate students have a clearer future career-personal goal, which is their transition to a postgraduate programme. In contrast, postgraduate students enrich their interests and discover new approaches and fields during their postgraduate studies, something that leads to expanding their career options and future career-personal goals. This also implies that the transition point of entering the labour market in Greece, has been partly shifted to the completion of postgraduate studies. Besides, Tsatsaroni and Sarakinioti (2018), who conducted relevant research in the field of post-secondary education in Greece, suggest that the large availability of lifelong learning opportunities, along with individuals’ perceived employability, increase the complexity [and therefore reduce the clarity] of career decision-making processes for young individuals.

A major limitation in this research was that the sample consisted only of university students. Further studies should be conducted including various samples of adolescents, employed and unemployed people with various occupations, to further test its factorial equivalence corroborating the utility of the scale for research purposes. Moreover, testing measurement invariance across different samples could provide more robust evidence of construct validity. Additionally, future research aiming at further supporting the validity of LPRS should support convergent validity providing additional data about its relations with intrapreneurial self-capital skills and outcomes, like psychological sustainability and well-being. Discriminant validity should also be examined by studying the relationship of the LPRS dimensions with relevant career constructs with which are hypothesized to be negatively associated, such as acquiescence. Finally, it would be of great interest to examine the economic crisis impact on Greek university students’ life-project reflexivity dimensions, as they develop career-life projects in a turbulent and challenging socioeconomic context. Future research should also focus on assessing the full cross-cultural invariance of the LPRS. Nevertheless, reliability and concurrent validity measures of the Greek LPRS, suggest that it is a multidimensional construct, composed of three specific dimensions (Authenticity, Acquiescence and Clarity/Projectuality). Therefore, it could be used effectively for career construction and primary preventive interventions also in the Greek context, with respect to setting goals and assessing change in life project reflexivity for the challenges of the 21st century.

Conclusion

Based on the results of this research, the Greek version of the LPRS is considered equivalent to the Italian version in terms of psychometric characteristics and factor structure. The good psychometric properties of the scale suggest its appropriateness for exploring career-life projects of university students in Greece, as well as for constructing and assessing career counseling interventions focusing on life project reflexivity. Students need to develop reflexivity resources in order to be prepared to enter the labour market and manage unexpected or unforeseen career transitions by setting up meaningful goals and projects based on authenticity and clarity. The authors contend that career-related interventions targeting the reinforcement of students’ career-life projects should be a fundamental goal of the Greek university curricula; however, individuals also need to take greater personal responsibility for directing and redirecting their lives in order to design and manage their action in a sustainable way. The aforementioned results suggest possibilities for the future use of the Greek LPRS in the career counseling practice, as the LPRS is a useful tool that counselors, teachers and other practitioners interested in assisting individuals may use. It is noteworthy that the development of curricula should address the three dimensions of LPRS, Authenticity, Clarity/Projectuality and Acquiescence, in the educational setting. Through such programmes, students may be assisted in forming clear career and personal projects that will be based on their authentic values and will be conveyed with personal meaning. In addition, the Greek version of LPRS, as a multidimensional construct composed of three specific dimensions (Authenticity, Acquiescence and Clarity/Projectuality) could be administered to participants before the beginning of the programme, in the middle and at the end in order to assess possible fluctuation in students’ career-life projects.

Bibliography

Anastasi, A., & Urbina, S. (1997). Psychological testing (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Arachchige, B. J. H., & Robertson, A. (2013). Employer Attractiveness: Comparative Perceptions of Undergraduate and Postgraduate Students. Sri Lankan Journal of Human Resource Management, 4(1), 33-48.

Benson, V., Filippaios, F., & Morgan, S. (2009). Evaluating Student Expectations: Social Networks in Career Development. Paper presented at the Society for Research into Higher Education (SRHE) Annual Conference 2009: Challenging Higher Education: knowledge, policy and practice. Newport, United Kingdom.

Benson, V., Filippaios, F., & Morgan, S. (2010). Online Social Networks: Changing the face of business education and career planning. International Journal of eBusiness Management, 4(1), 20-33.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588-606.

Centre of Educational Policy Development (KANEP), & GSEE (Greek General Confederation of Labour) (2014). The basic data of Education: the Greek Higher Education. Part B: the national context of reference 2002-2012. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.kanep-gsee.gr/sitefiles/files/etekth2014.pdf

Converso, D., Sottimano, I., Molinengo G., & Loera, B. (2019). The Unbearable Lightness of the Academic Work: The Positive and Negative Sides of Heavy Work Investment in a Sample of Italian University Professors and Researchers. Sustainability, 11(8), 1-16.

Di Fabio, A. (2014a). Intrapreneurial Self-Capital: A New Construct for the 21st Century. Journal of Employment Counselling, 51, 98-111.

Di Fabio, A. (2014b). Career counselling and positive psychology in the 21st century: new constructs and measures for evaluating the effectiveness of intervention, Journal of Counsellogy, 1, 193-213.

Di Fabio, A. (2017). A review of empirical studies dealing with employability and measures of employability. In J. G. Maree (Ed.), Psychology of career adaptability, employability, and resilience (pp. 107-123). New York, NY: Springer.

Di Fabio, A., & Kenny, M. E. (2016). From decent work to decent lives: Positive Self and Relational Management (PS&RM) in the 21st century. In A. Di Fabio & D. L. Blustein (Eds.), From meaning of working to meaningful lives: The challenges of expanding decent work. Research topic in Frontiers in Psychology. Section Organizational Psychology, 7, 361.

Di Fabio, A., & Maree, J. G. (2016). A psychological perspective on the future of work: Promoting sustainable projects and meaning-making through grounded reflexivity. Counseling. Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni, 9.

Di Fabio, A., Maree, J. G., & Kenny, M. E. (2018). Development of the Life Project Reflexivity Scale: A New Career Intervention Inventory. Journal of Career Assessment, 27(2), 358-370.

Guichard, J. (2005). Life-long self-construction. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 5, 111-124.

Guichard, J. (2009). Self-constructing. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(3), 251-258.

Guichard, J. (2013, November). Career guidance, education, and dialogues for a fair and sustainable human development. In Inaugural conference of the UNESCO chair of Lifelong guidance and counseling, University of Wroclaw, Poland.

Guichard, J. (2016). Reflexivity in life design interventions: Comments on life and career design dialogues. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 97, 78-83.

Guichard, J., Pouyaud, J., De Calan, C., & Dumora, B. (2012). Identity construction and career development interventions with emerging adults. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(1), 52-58.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Model, 6, 1-55.

Karavia, A. (2015). Mothers’ career adaptability and related factors. Unpublished Master Thesis, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Philosophy, Pedagogy and Psychology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece.

Kassotakis, M. (2014). The variance of professional life and its impact on vocational guidance. Review of Counselling and Guidance, 103, 93-118.

Maree, J. G., & Di Fabio, A. (2015). Exploring New Horizons in Career Counseling: Turning Challenges into Opportunities. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Mikedaki, K. (2015). Career adaptability inventory: psychometric characteristics and relationship with self-esteem of Greek students. Unpublished Master Thesis, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Philosophy, Pedagogy and Psychology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece.

Morgan, J., & Farsides, T. (2009). Measuring meaning in life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10. 197-214.

Mylonas, K., Furnham, A., Alvaro, J-L., Papazoglou, S., Divale, W., Cretu, R.Z., …, & Boski, P. (2016). Explanations of unemployment: an eight-country comparison. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 6(9), 344-361.

OECD (2018). Education at a Glance 2018: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing

Patton, W., Bartrum, D. A., & Creed, P. A. (2004). Gender differences for optimism, self-esteem, expectations and goals in predicting career planning and exploration in adolescents. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 4(3), 193-209.

Savickas, M. L. (2011). Career Counseling. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Savickas, M. L. (2013, September). Life designing. What is it? Invited Keynote at IAEVG International Conference, Montpellier, France.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychological Research, 8, 23-74.

Sidiropoulou-Dimakakou, D., Mikedaki, K., Argyropoulou, K., & Kaliris, A. (2018). A Psychometric Analysis of the Greek Career Adapt-Abilities Scale in University Students. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 10(3), 95-108.

Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioural Research, 25, 173-180.

Stoddard, S. A., Zimmerman, M. A., & Bauermeister, J. A. (2011). Thinking about the future as a way to succeed in the present: A longitudinal study of future orientation and violent behaviors among African American youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 48(3-4), 238-46.

Tsatsaroni, A. & Sarakinioti, A. (2018). Thinking flexibility, rethinking boundaries: Students’ educational choices in contemporary societies. European Educational Research Journal, 17(4), 507-527.

van der Vijver, F., & Leung, K. (1997). Methods and Data Analysis for Cross-Cultural Research. London: SAGE Publications.

Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Baliousis, M., & Joseph, S. (2008). The authentic personality: A theoretical and empirical conceptualization and the development of the Authenticity Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 385-399.

1 Department of Educational Studies, School of Philosophy, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece.

2 School of Education, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece.

3 Department of Educational Studies, School of Philosophy, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece.

4 Department of Educational Studies, School of Philosophy, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece.

5 Department of Educational Studies, School of Philosophy, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece.

6 Department of Educational Studies, School of Philosophy, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Grecia.

7 School of Education, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Grecia.

8 Department of Educational Studies, School of Philosophy, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Grecia.

9 Department of Educational Studies, School of Philosophy, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Grecia.

10 Department of Educational Studies, School of Philosophy, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Grecia.