Vol. 23, n. 1, febbraio 2024

Prospettive e Modelli internazionali

Giftedness, achievement, and inclusion: A discourse analysis1

Simone Seitz,2Michaela Kaiser,3Petra Auer4 e Rosa Bellacicco5

Sommario

I dibattiti sulla promozione della giftedness e del rendimento scolastico hanno portato, nell’ultimo decennio, allo sviluppo di un’ampia consapevolezza pubblica. Tuttavia, la relazione tra giftedness, rendimento e inclusione nei discorsi sulla tematica risulta spesso incoerente. Il presente contributo cerca perciò di illustrare i meccanismi in cui si articola il sapere scientifico sulla promozione della giftedness e del rendimento scolastico e la loro relazione con il concetto di inclusione, ponendo particolare attenzione all’influenza esercitata dall’agenda inclusiva internazionale su di essi. Analizzando la letteratura scientifica internazionale attraverso il Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse (SKAD), lo studio indaga le strutture discorsive e le regole di formazione di tali discorsi. Analizzando il caso esemplare di due testi altamente in contrasto tra loro, sono emerse linee di argomentazione e interpretazioni molto diverse sulla relazione tra, rispettivamente, giftedness e inclusione e inclusione e giftedness. I risultati indicano che un orientamento fondato sul concetto di giustizia sociale in termini di capabilities potrebbe essere una soluzione per riconciliare i due concetti, in quanto consentirebbe a tutti gli alunni di sviluppare equamente le loro diverse abilità, riconoscendo la responsabilità delle scuole nel garantire le opportunità necessarie.

Parole chiave

Giftedness, Rendimento scolastico, Inclusione, Equità educativa, Analisi del discorso.

INTERNATIONAL MODELS AND PERSPECTIVES

Giftedness, achievement, and inclusion: A discourse analysis6

Simone Seitz,7Michaela Kaiser,8Petra Auer,9 and Rosa Bellacicco10

Abstract

Over the past decades, debates on the promotion of giftedness and achievement in schools have gained widespread public awareness. However, the relationship between giftedness, achievement, and inclusion within the related discourses appears to be inconsistent. Therefore, the present contribution tries to illustrate the mechanisms by which scientific knowledge about the promotion of giftedness and achievement in school is structured and its relation with the concept of inclusion. In doing so, particular emphasis is placed on the international inclusion agenda. By means of a discourse analysis of the international scientific literature following the Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse (SKAD), the underlying study investigated the narrative formations and the stabilising rules of interpretation of these discourses. By exemplifying two maximally contrasting texts, it revealed quite distinct lines of argumentation and interpretations regarding the relationship between giftedness and inclusion or inclusion and giftedness, respectively. The findings lead to the conclusion that orienting towards the concept of social justice in terms of capabilities might be a solution to reconcile these two concepts, since this orientation enables all children to equally develop their diverse abilities, with schools taking on the responsibility to provide the necessary opportunities.

Keywords

Giftedness, Achievement, Inclusion, Educational justice, Discourse analysis.

Giftedness and achievement in relation to the agenda of inclusion

The concept of giftedness and its relation to schooling, educational success, failure, and inequity have been the subject of heated debates for a long time (Coleman et al., 1966; Bourdieu, 2006; Margolin, 2018) — despite the lack of a clear definition of the concept and the recognition that giftedness seems to be something that emerges specifically at different times and within different contexts (Borland, 2021; El Khoury & Al-Hroub, 2018). From a historical perspective, it can be argued that at the beginning of the twentieth century, giftedness was seen as a personal characteristic along with the establishment of intelligence measurements (Borland, 1996; Terman, 1916; Hollingworth, 1926). In this frame, it was associated with conceptualisations of normalcy within children’s development (Kelle & Tervooren, 2008) and partly with the idea of selection (Stern, 1916; Weigand, 2011).11 Although, within the context of the reception of critical sociological writings on education (Bourdieu, 1982, 2006), the term was later criticised at an international level as an inequity-reinforcing social construction, in the last two decades various operationalisations have been presented (Sternberg, 2019; Borland, 2021).

Some of these attempted to describe more in detail the relationship between education, development, and disposition as well as educational institutions in this context (e.g., Sternberg, 2003; International Panel of Experts for Gifted Education [iPEGE], 2009; Renzulli & Reis, 2014; Marsili, Dell’Anna, & Pellegrini, 2023). However, within the present contribution, we argue that quite often, giftedness seems to be (still) strongly associated with measurable academic achievement (Reh & Ricken, 2018; Schäfer, 2018). Strengthened by large-scale assessments, debates on academic achievement and performance enhancement have multiplied in the international discourse (e.g., Popkewitz, 2011; Pereyra, Kotthoff, & Cohen, 2011), and the concept of giftedness has regained prominence. The intensified research activities on the topic of achievement are thus reflected in the debates on giftedness (International Panel of Experts for Gifted Education [iPEGE], 2009; Weigand, 2021).

We address this issue within a framework of understanding giftedness as socially constructed and interconnected with power-related dynamics which hold significance in educational (in)equity. We do so, guided by theoretical approaches of educational sociology and inequity-critical research. We will also show how this close nexus of giftedness and achievement is described in correlation to the inclusion discourse. We assume that within the briefly described discourses on giftedness, symbolic orders are developed and consolidated in social contexts (Böker & Horvarth, 2018). These turn to knowledge regimes that institutionalise a knowledge order for specific practical fields (Foucault, 1977; Berger & Luckmann, 1977; Grek, 2009). Accordingly, norms are historically changeable in this regard and can differ culturally (Baird, 2009). At the level of the organisation instead, norms of giftedness are attributed to individuals and connected with constructs of normalcy and difference in achievement (Powell & Haden, 1984; critically Cross & Coleman, 2005; Böker & Horvarth, 2018). The latter triggers subjectification effects in social interactions within the classroom and is correlated with the production and negotiation of social differences (Boaler, William, & Brown, 2005; Gellert, 2013; Ricken, 2018; Wagner-Willi et al., 2018). Thereby, reference is often made to habitual assignment problems and hegemonies (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1971; Kramer, 2017; Riefling & Koop, 2018), which, in more recent discourses, are also described as entanglements of classism, racism, sexism or ableism (Hooks, 2000; Gomolla, 2012; Staiger, 2018; Akbaba & Bräu, 2019). Thus, children seem to be constantly confronted with hegemonic expectations of adjusted behaviour and achievement in school (Machold & Wienand, 2021; Breidenstein & Thompson, 2014; Flashman, 2012). These dynamics are inseparable from structural orders like tracking and selection as well as policy making that shape behind-the-scenes norms (Horvarth, 2018; Becker et al., 2020; Sandri, 2014; Van de Werfhorst & Mijs, 2010). Overall, it can be stated that national control of education systems is reciprocally transgressed by supranational governance, and normative impulses become apparent in the discourse in multiple ways.

A second prevailing agenda of international discourses is the one related to inclusion (United Nations, 2006, n. d.). In this context, prescriptive approaches along administrative classifications of «special educational needs» (SEN) in schools have long been criticized as being guided by habitual concepts and for reinforcing inequity (van Essen, 2013; Edelstein, 2006). The essentialisation of achievement failure through such prognostically oriented diagnosis (in the form of SEN) has also been the subject of severe criticism, particularly in the inclusion-related discourse (Ebersold et al., 2019; Migliarini, D’Alessio, & Bocci, 2020). For in this way, achievement failure and achievement differences would be powerfully turned into an apparent fact to be subjectivised by those affected (Machold & Wienand, 2021; Boger, 2018). On the other hand, giftedness is partly interpreted as a form of SEN within the giftedness discourse. Critically, this form of SEN would receive comparatively little attention overall when compared to achievement failure (Dai, 2022; Dell’Anna & Marsili, 2022). This critique can be seen as part of a discourse on the up- and downgrading of low-achieving and high-achieving students, triggered by largescale assessments.

At their respective national level, these dynamics are affected by the specific system conditions with regard to stratification (Hillmert & Jacob, 2010) as the internationally formulated inclusion mandate is recontextualised in vastly different ways in the educational state policies under consideration (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2020; Powell, 2018). The development of an inclusive education system is meanwhile seen as a global paradigm (Köpfer, Powell, & Zahnd, 2021; Amrhein & Naraian, 2022), whereby the normative demands of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities-UNCRPD (United Nations, 2006) are taken up in education policy and spelled out differently at international, national, and regional levels. In this respect, inclusive education is associated with the analyses of barriers and of discrimination (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010), which are situated in historically developed and culturally and politically shaped systems. Overall, inclusion has become a global relevant, interdisciplinary concept, nevertheless international and comparative issues in the context of inclusive education have so far been a scarcely explored field of research (e.g., Köpfer, Powell, & Zahnd, 2021; Amrhein & Naraian, 2022). This is meaningful for the question pursued here — as it cannot remain without consequences for academic discourses on giftedness and achievement. Overall, it can be said that there is still limited knowledge regarding how giftedness and inclusion are dealt with in relation to one another in the specific discourses, both at national and international levels.

Based on this, we raise the question of how the scientific discourse(s) on giftedness and inclusion are constructed and which patterns of interpretation of diversity, inclusion, giftedness, achievement and (in)equity are produced and reproduced within it. In doing so, we understand the promotion of giftedness and inclusion as two discourse-relevant and interacting programmatic approaches. Both provide important impulses for the scientific discourse and are, in their scientific development, significantly shaped by two political agendas: The international large-scale assessment studies such as PISA (OECD, 2015) and the international conventions on inclusion and sustainability (United Nations, 2006, n. d.).

Methodological approach and design

The outlined study follows the Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse (SKAD; Keller, 2013), which aims to investigate the narrative formations and stabilising rules of discourses thereby providing information on social knowledge structures and knowledge policies (Keller, 2003, 2005, 2011a, 2013; Viehöfer, Keller, & Schneider, 2013). The central assumption is that, in and through discourses, the sociocultural meaning and facticity of social realities are constituted as social reality is contingent and discursively produced (Berger & Luckmann, 1977), which is why «speaking about» is a discursive as well as a social practice. Analyses of discursive practices are thus concerned with a precise description of statements in their logic and the frame of the conditions of their appearance (Bublitz, 2003). Discourses can be understood as structuring frameworks to institutionalise symbolic meanings for specific fields of practice.

Sampling strategy

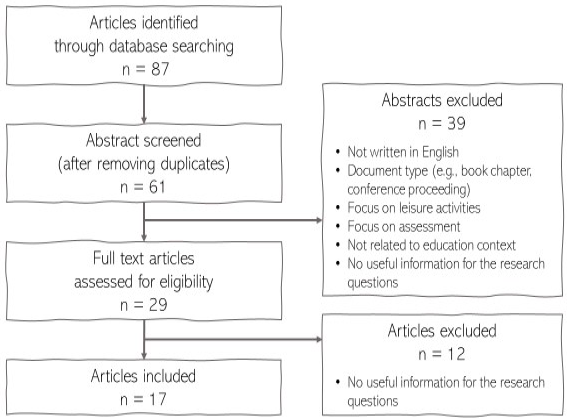

Regarding the reconstruction of this discursively constructed scientific reality, scientific texts on the relationship between giftedness, achievement, and inclusion were analysed. Consequently, the focus is on a special discourse (Keller, 2011a, 2013), that is mainly constructed in scientific journals, and further in book publications and conferences. In this regard, the compilation of the data corpus was — for reasons of comparability — restricted to scientific journal articles, which were systematically searched in the databases ERIC and Education Source.12 We limited the search to the time frame 2011-2020 and peer-reviewed journals. The time marker was set accordingly, as it is assumed that the ratification of the UN CRPD (United Nations, 2006) by many countries during the preceding years had set important impulses for the discussion of giftedness. Overall, 87 articles were found, of which 61 were retained after deleting duplicates. After screening the abstracts according to the theoretical sampling13 (Strauss & Corbin, 1996), 29 articles were identified as potentially meeting the inclusion criteria (see Figure 1). Consequently, the full texts of these articles were assessed, and a further 12 publications had to be excluded since they did not provide any useful information on the research question (e.g., many of them focused only on inclusion or giftedness and not on both concepts). This led to a final text corpus of 17 publications, which were then analysed through the SKAD approach.

The procedure of data analysis in the context of SKAD focuses mainly on the interpretative-analytical reconstruction of the statements (Keller, 2005, 2011b) using strategies and instruments of Grounded Theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1996). This comprises the analysis of (1) the situatedness and material form and (2) the formal and linguistic-rhetorical structure, as well as (3) the interpretative-analytical reconstruction of the content, even though these dimensions do not follow a strict order and can differ in the weight attributed to them (Keller, 2011a).

Figure 1

Flowchart of the selection procedure (adapted from Brunton & Thomas, 2012).

Analysis

Within the present study, the texts were analysed along the coding steps of open, axial, and selective coding to elaborate the narrative structure underlying them. This way, dispositifs14 are reconstructed (Keller, 2013) and the data is interpreted to develop categories and work out the relations between these. Interwoven with these steps was an analysis of the situatedness and the material form, that is, the analysis of the respective origin, the disciplinary self-positioning of authors, the assumed addressees, and the impact of the text. This implies a brief description of the authors’ profiles and their role in the scientific discourse, the description of the journal type and the recipients. We therefore researched the following context information for each article: the Journal, the Journal area, the author(s)’s disciplinary field, the impact factor of the Journal and the national context (see Table 1). In line with the research ethics principle of non-harming, all publications were anonymised (e.g., Flick, 2007; Hopf, 2004). The chosen articles originate from 15 different journals (with three articles published in the same Journal) which have also been anonymised.15 All of them can be attributed to the area of education research but belong to different subdisciplines as can be derived from their main aim being cited on their websites as well as from the authors’ disciplinary field. Regarding the impact factor we decided to report the SCImago Journal Rank (SJR) since it considers the prestige of the citing journal (i.e., it starts from the concept of prestige transfer between journals through their citation links). We assume that prestigious journals do have a greater impact on the discourse.16 In terms of national context, 7 articles can be localised in the US context, 4 in Europe, 2 in Asia, 2 in South Africa, and 2 publications could not be attributed to a specific national context. From the 17 articles included in the analysis, 8 reported empirical studies and 9 can be considered theoretical articles (i.e., 1 systematic review).

Table 1

|

Anonymised Publication |

Area |

Author(s)’s disciplinary field |

Journal Impact Factor17 |

National context |

Publication type |

|

A, 2020 |

Education |

Elementary Education; Educational Sciences |

SJR = not available H-Index = not available |

Turkey |

Empirical study |

|

B, 2018 |

Education |

Special Education and Human Resource Development; Inclusive Education |

SJR = 0.836 H-Index = 47 |

Japan |

Empirical study |

|

C, 2018 |

Education |

School Development; Education |

SJR = 0.496 H-Index = 23 |

Germany |

Theoretical article |

|

D, 2011 |

Education |

Gifted Education; Education Consulting |

SJR = 0.367 H-Index = 3 |

USA |

Theoretical article |

|

E, 2013 |

Education |

Psychology and Gifted Education |

SJR = 0.367 H-Index = 3 |

USA |

Theoretical article |

|

F, 2012 |

Education |

Counselling and Special Education |

SJR = 0.216 H-Index = 25 |

Jordan |

Empirical study |

|

G, 2012 |

Education |

Educational leadership; Teacher education |

SJR = 0.432 H-Index = 25 |

USA |

Empirical Study |

|

H, 2014 |

Education |

Special Education and Teaching and Learning |

SJR = 0.549 H-Index = 39 |

USA |

Theoretical article |

|

I, 2019 |

Education |

Education; Educational Psychology |

SJR = 1.217 H-Index = 40 |

Spain |

Empirical Study |

|

J, 2018 |

Education |

School Counselling and School Psychology Programs; Counselling Psychology |

SJR = 0.33 H-Index = 18 |

USA |

Theoretical article |

|

K, 2017 |

Education |

Mathematics Education |

SJR = 1.196 H-Index = 44 |

South Africa |

Empirical study |

|

L, 2016 |

Education |

Urban Community Teacher Education; Education and Human Development; Teacher Training |

SJR = 0.41 H-Index = 9 |

USA |

Theoretical article |

|

M, 2014 |

Education |

Gifted Education and Talent Development |

SJR = 0.372 H-Index = 13 |

Switzerland |

Theoretical article |

|

N, 2013 |

Education |

Educational Psychology |

SJR = 0.408 H-Index = 27 |

South Africa |

Empirical study |

|

O, 2019 |

Education |

Teacher Education; educational administration and policy; special education |

SJR = 0.226 H-Index = 8 |

/ |

Systematic Review |

|

P, 2019 |

Education |

Gifted education and Talent Development |

SJR = 0.367 H-Index = 3 |

USA |

Empirical Study |

|

Q, 2012 |

Education |

Early childhood, gifted children; psychology; clinical psychology |

SJR = 0.602 H-Index = 28 |

/ |

Theoretical article |

Publications included in the discourse analysis and context information.18

Further, the formal and linguistic-rhetorical structure of the texts was analysed, considering whether the article is empirical or theoretical (e.g., systematic review, discussion, or meta-analysis) as this also determines its structure, style, or rhetoric. Based on the sampling strategies (see Figure 1), it can be assumed that the texts consistently addressed the international scientific community and sought to position themselves in this discourse. The scientific (written) language has a pivotal role in this (Atkinson, 1996), as «scientific language and discourse emerge in a cooperative and competitive struggle among scientists to create the knowledge base of their field, to establish themselves in relation to other scientists and to other professional groups, and to gain influence and control over political and socioeconomic means» (Gunnarsson, 2014, p. 99). However, different discourses of giftedness research, inclusion research and related research lines within the disciplines of educational research, educational psychology and educational sociology were addressed in these texts, which had to be considered in the analysis (Truschka & Bormann, 2013). Since the data corpus of the present analysis included only peer-reviewed articles, the underlying discourse(s) can be further understood as being subject to a specific selection process. Because within academic disciplines and discourse families, the roles of authors and journal reviewers can coincide, the field of discourse both reflects and powerfully checks itself through these procedures. In other words, the analysis of which texts show to be assertive within these procedures is already a first relevant finding.

As the authors of this article are themselves inevitably part of the academic discourse, during the analysis process it was even more relevant to compare and discuss the findings continuously and critically in different research groups, following the research style of Grounded Theory, and reflecting on their location-boundness (Mannheim, 1980) in the analysis (Breuer, Mey, & Mruck, 2011; Strübing, 2014).

Findings from and in-depth discussion of two contrasting texts

To make the findings of our analysis comprehensible and to illustrate them, two contrasting texts (C, 2018 and D, 2011 as highlighted in Table 1) are discussed in detail below. The methodological rationale behind this choice will be briefly explained before a presentation of the results. For the latter, the context of the manuscript will be described, then the position of the author(s) is presented and finally the analysis.

Methodological argumentation

In the text corpus, the international inclusion policy conventions — especially the Salamanca Declaration (UNESCO, 1994) and the Large-Scale Assessment Studies (PISA) — are dominantly introduced in the discourse as markers re-negotiating the concept of giftedness as well as the pedagogical approach to giftedness in the light of inclusion and achievement. However, the arguments that followed from this differed considerably. Therefore, in the present article, we will elaborate on our main findings using the principle of maximal contrasting as defined in Grounded Theory (Strauss, 1987; Keller, 2011a). This procedure allows to elaborate «the total spectrum of the discourse(s) within a corpus and thus to work out several discourses on a single theme, or the heterogeneous components within a single discourse» (Keller, 2013, p. 100). Within our data corpus, two texts proved to be maximally contrasting during our analysis. In this section, we discuss the structure of these texts in depth and, at the same time, make our methodological approach transparent.

First exemplary text (publication C)

Publication C (2018) is a theoretical article related to the European discourse. It was published in a Journal with an SJR value of 0.496 and an H-Index of 23. The journal advocates the engagement in school development by focusing on educational objectives and social justice. It addresses an international readership ranging from teachers to academics and consultants. Author* C is affiliated with the disciplinary fields of research on school development and educational systems. The article focuses on educational equity for students who are described as socially «disadvantaged». The identification of educational equity and equal opportunities as the same thing is identified by the authors as a fallacy. The construct of achievement is perceived from the perspective of educational equity as a basic principle of inclusion. Hence, reference to the inclusion discourse is not made starting from the construct of giftedness, but rather the other way around. This way, selective mechanisms in the promotion and recognition of talent and achievement are questioned in the text. Referring to a frame of educational justice, author* C point* out that the latter is not only evident by the fact that all children have access to education but that the education offer considers the specifics of their life situations. The latter is described as the crucial factor allowing these children to achieve in school and demonstrate their talents.

In particular, the concept of «diligence» as an indicator of achievement is criticised in the article as culturally biased, as it is attributed especially to students from well-educated families with high aspirations for their children, thus reinforcing inequity. Linked to this, author* C emphasise* the relevance of the extent to which teachers in schools — in so-called «challenging regions» — also assume that children might be gifted and are identified as gatekeepers for the educational success of their students.

In this reading and following author* C, the equitable promotion of giftedness and achievement aims to address socio-economically determined educational inequities as a pedagogical-didactic challenge in the sense that unequal starting conditions are considered in a habitus-sensitive manner. In this context, reference is made, above all, to students whose social background «[...] is furthest removed from the curriculum content». The latter is associated in the article with the affiliation to ethnic minorities and families with low qualification levels and described as deficient from a supposed habitual school norm. Based on this, opportunities are outlined to address educational inequities by changed teaching strategies. Concerning teachers’ professionalism, sensitivity and reflexivity regarding habitus, different living conditions and milieu-specific activity patterns as they arise through diverse socialization conditions are highlighted by author* C — in combination with diagnostic and didactic competencies. Both refer to the specific situation of teaching and learning in schools located in «disadvantaged» areas.

The analyses of author* C point first to a notion of specific teaching «characteristics» to promote students’ learning within specific segregated environments. This assumption leads to an implicit norming of social and ethnic backgrounds and a reification of difference. The argumentation within the article is based on the assumption that schools in socially «disadvantaged» settings face difficulties in providing high-quality, gifted-appropriate teaching. In doing so, the negative characteristics of the repeatedly called «deprived», «segregated», and «disadvantaged» schools, their exclusionary character come into focus as the development of talent and achievement of students at schools in socially «disadvantaged» areas is conceptualised as deficient by author* C. Addressing children at risk of exclusion through the sensitivity for habitus is therefore called for to achieve a coordination between learning and educational opportunities at school and learning conditions at home.

In the article, deviance as «disadvantaged», «challenged», and «socially disadvantaged» is constructed in comparison to so-called «privileged» schools. Through this, an essentialisation of «disadvantage» is introduced, which leads to a takeover of the subjects conceived in this way and decisively models the self-perception of «disadvantaged» individuals and groups by associating them to specific identities and characteristics (cf. Kollender, 2016). With Foucault (1977), this line of argumentation could also be read as a practice of disciplinary power. It is directed at the supposedly deviant individual and aims to produce subjects as performers of existing relationships of inequity by means of pedagogical instruments — in this case, the promotion of giftedness.

Educationally appropriate support is described in the article as the empowerment of members of a group at risk. This need-based resource management of reacting to differences as a reflection of diverse socialisation-related inequities subsequently legitimises specific supportive practices. In this respect, the position presented in the text can be understood as embedded in the field of tension between protection or promotion and stigmatisation (Kottmann, 2022; Boger & Textor, 2016) as the giftedness of «disadvantaged» students seem to differ from those of other students. The «disadvantage» is thus withdrawn from further critical analysis of inequity and asymmetry of power between school and family and becomes an individual characteristic. Consequently, readiness for high academic achievement is associated with measurable socio-economic categories. Through the latter, it seems further possible to explain inequities and position them primarily with the students and their families. Therefore, to what extent publication C can fulfil the concern formulated in the text regarding how to contribute to educational justice and inclusion in schools is questionable, because the impression arises that, despite the clearly formulated value frame of reducing inequities these are partially unconsciously reproduced.

Second exemplary text (publication D)

Publication D (2011) is a conceptual paper related to the US-American discourse. Concerning citation metrics, the journal has an SJR value of 0.367 and an H-index of 17. The journal defines itself as a critical information provider for an international readership that includes mainly teachers and administrators involved in aspects of giftedness in childhood. According to the readership, it is about gifted education, effective gifted and talented programs, and aspects of giftedness and underachievement. Author* D is affiliated with the disciplinary fields of gifted education and counselling.

Following author* D (2011), the contribution is motivated by the identification of «dramatic» developments, which highlight the fact that the needs of gifted students are ignored in educational practices and policies. According to this line of argument, this comes at a high price to society. The identified risks of scaling back specific giftedness programmes are described by author* D as a threefold loss, which is semantically reinforced by the repetition of the verb «lose» three times in one sentence. Based on this, the article aims explicitly to present a cost-neutral and «inclusive» concept of giftedness promotion in schools which can be both fair and effective. In the article, the need for specific programmes is then justified by the increasing pressure to improve students’ achievement and the simultaneous requirement to secure equality of chances under the condition of reduced budgets. Even though the text focuses on pedagogical reflections around a suggested concept of school development by grouping, the economic argument plays a dominant role in the text. The argumentation frequently relies on it — it is present in almost every paragraph — mentioning budgets and funding.

The approach outlined in the text foresees a systematic support of the gifted within mainstream schools, which is ensured through early identification. Following author* D, these children are considered to have exceptional learning needs that set them apart from others and require a specific setting characterised by a challenging curriculum and options for divergent critical thinking. As a result, the creation of a difference dominates the text using adjectives like «exceptional» and «different». According to this approach, specific positively connotated learning activities (e.g., explorative self-regulated learning) are not open to all students but can be achieved through competition and continuous assessment in the classroom. Following the argumentation line, students must qualify within mainstream classroom practices through a differentiation process based on regularly offered opportunities. Thus, differentiation becomes a privilege granted through public competition in class. Based on the continuous practice of assessment, students are constantly upgraded and downgraded depending on their latest performance and pace of learning. In addition, following author* D, the autonomous, in-advance, early completion of weekly given homework, which everyone is encouraged to do, rationalises the upgrading of students to the high-achievers group. Overall, this reveals a value system heavily based on effort, competition, and assertiveness with a focus on students as academic learners at school. Instead, the reality of diverse life situations is not in the foreground. At the same time, competitiveness is positioned as a distinctive nature-given characteristic of gifted children in the text, including their wish to challenge their peers. In line with the argument, this outlined trait «urges» children to strive to perform better, especially if among intellectually comparable peers.

In the article, the grouping of gifted students is continuously described as contributing to well-being, self-confidence, and social belonging within the specific group. Presumably, this is done to implicitly introduce the assumed loneliness of gifted students when they are not among «their» peers. Nevertheless, strengthening peer relationships in mainstream classrooms or school communities seems not to be conceptualised at all by author* D. Instead, it seems to arise «naturally» through common interest in competition within clustered groups. Overall, the full-time grouping within mainstream schools is introduced in the article as a systematic, school-wide sorting machinery. The model of grouping is classified as inclusive giftedness education, and what is emphasised is that all students have the chance to qualify for participation in gifted-specific measures through peak performance — including «second language learners». Four best practice examples are described in the text. These are not methodologically prepared; rather, they serve to illustrate the argumentation, not as empirical data. In parallel, specific qualifications of teachers are claimed to be able to meet the seen-as-exceptional needs of gifted students.

Following the proposed and illustrated model in the text, students are taught in «sorted» classes from the moment they enter (middle) school: according to tests and teacher assessments, all students are classified into five groups: so-called highly and profoundly gifted students, gifted students, high achievers, average to low and far below average learners. By doing so, author* D suppose* that students’ ability range in each classroom is reduced, which is seen as facilitating effective teaching. The grouping procedure is illustrated in a whole series of tables, which occupy much of the article and are characterised by axis symmetry. The term «balance» is strikingly dominant in the text: it is used five times in combination with «grouping». According to author* D, grouping suits the creation of an overall balance between ability and achievement. As such, it is in line with the highlighted effect that students whose performance is far below average are not in class with gifted students. Thereby, grouping is presented by author* D as an aesthetic process comparable with the colour composition of artworks, which seems to suggest aesthetics and stability through symmetry and balance. An explicit connection to inclusive pedagogy is made in the article by referring to the rationale behind the «Response to Intervention Model» (Jimerson, Burns, & Van der Heyden, 2016). The latter categorises all students into at-risk groups for (future) performance failure and behavioural problems and this is considered as perfectly matching by author* D.

Overall, Text D frames school as an arena of meritocracy, closely reminding of the saying that children are the «the masters of their own destiny». This approach presupposes an equality of starting positions when entering school and an autonomy of young learners, since it is up to them to achieve at school through their own efforts. According to author* D, children, who are considered gifted, are entitled to attention and specific support. Consequently, differences are produced and hierarchised. The concept of achievement is conceptualised as a distance-creating factor between students, which arises as a matter of course of their natural talents supposed as different. This is done against the background of the assumption that school achievement is attributed to different natural talents and that the school is responsible for the development of these natural talents. However, the proposed sorting by ability systematically prevents gifted students from learning in classes with «low achievers». Overall, it provides the effective prevention of full inclusion despite advocating for inclusive giftedness education, which addresses all students, in particular «second language learners». However, this is not explained or elaborated in more detail.

Overall discussion of the two contrasting texts

The overall aim of the present study was to understand how the scientific discourse on giftedness and inclusion is constructed. For this purpose, it is relevant to unravel which patterns of interpretation of terms such as diversity, inclusion, giftedness, achievement and (in)equality or (in)equity underlie the texts and which narrative structures are behind these patterns. Based on this research interest, in the following, some crucial aspects of the two texts are brought together. In doing so, we will elaborate on both contrasting aspects and possible commonalities.

First, although both contributions deal with aspects of school development, the publications contrast in terms of the specific topic they address. While publication C focuses explicitly on educational equity with a focus on so-called «socially disadvantaged» students in mainstream schools of segregated areas, publication D presents a cost-neutral and inclusive concept of giftedness promotion in mainstream schools. Author* C argue* within the frame of educational justice, which emphasises the critical examination of giftedness through the lens of educational justice and inclusion. The opposite seems to be the case in publication D, as inclusion is viewed through the lens of giftedness. Author* D move* mainly within the argumentation of giftedness education under the conditions of reduced budgets, which are mostly economic arguments. While Author* C question* and critically address* selective mechanisms in the promotion and recognition of talent and achievement, Author* D consider* selection or identification as necessary since they ensure the promotion of giftedness.

Regarding the patterns of interpretation of diversity, inclusion, giftedness, achievement, and (in)equality respectively (in)equity, being produced and reproduced within both texts, contrasting negotiations emerged from the analysis: In text C, diversity is understood as a real fact, which needs to be addressed in a way allowing marginalised groups to be provided with equal starting positions to not be excluded. Instead, in text D, student diversity is seen as a struggle for teaching, which needs to be counteracted by homogenisation through grouping. Consequently, inclusion is here interpreted as including gifted students in mainstream schools and is open to gifted «second language learners». In contrast, publication C draws upon a concept of inclusion in terms of highlighting the situations of certain marginalised minorities as distinct and stemming from the postulate of a universalist conception of education and social justice. Subsequently, giftedness, talent-based justice, and achievement are critically reflected because these concepts often lead to a lack of effective fairness if they are assumed to be something that first must prove itself in school through high achievement without taking into account the varying life conditions of students. Vastly different is the pattern of interpretation in text D, where giftedness refers to students identified as such based on an ability test, IQ-test or outstanding performance and marks them as having exceptional learning needs. These are consequently described in diagnosis-based terms as students with exceptional learning needs, where high academic achievement seems to be the target perspective but at the same time the prerequisite for the use of performance-enhancing measures that make this goal more probable.

Lastly, both texts differ in the patterns of interpretation of (in)equality and (in)equity, respectively: Text C mainly focuses on the concept of equal opportunities. The concept is critically reflected upon since it does not logically lead to educational justice and is intricately connected to the dynamics of discrimination. Instead, the concept of recognition justice, led by a particular focus on pedagogical relations based on personal recognition in school, is explicitly favoured. According to this latter approach, educational justice is primarily reflected in the fact that, while recognising the specific situation of each learner, paths for self-realisation and personality development are opened at schools. On the contrary, in Text D, a concept of (in)equality of chances is referred to but hardly addressed. It seems that inequality is merely perceived within the unequal distribution of budgets among the promotion of high- and low-achieving students. Referring implicitly to a concept of equality of chances, the comparability of children’s starting positions at their entry into school and their autonomy as young learners are assumed to be within their control to achieve high academic performance. They can do so through their efforts and thus gain access to specific enriching programmes via grouping. The responsibility in this regard is mainly a constant assessment to optimise grouping. In this context, it is repeatedly emphasised that so-called «second language learners» also receive access to the group of high achievers based on equal opportunities and under the condition of proven high individual performance.

To sum up, the contrasting comparison reveals extremely different interpretations of the relationship between giftedness and inclusion or inclusion and giftedness, which are influential for an understanding of educational equity and school practices connected to it. While in publication D, proven giftedness legitimises differentiation and selection, in publication C, the construct of giftedness becomes a benchmark for educational equity. This way, selective mechanisms in the promotion and recognition of giftedness and achievement are questioned.

Both publications reflect on school cultures and school development, positioning conceptual suggestions for educational practice in this broader frame. In publication C, this is described as a matter of professionalism in terms of habitus sensitivity, which is seen as decisive for school cultures. In text D, the focus, on the one hand, is on organisational aspects of school development to guarantee systematic and effective practices of grouping; on the other hand, a specific qualification of teachers is claimed in terms of pedagogical relationship building because gifted students would be more willing to take academic risks if they felt accepted and understood by their teachers.

Even though the two publications proved to be maximally contrasting during our analysis, we could elaborate on one central commonality: thinking in groups or categories and creating a difference. In text C, the mere descriptive use of words such as «deprived», «challenging» or «socially disadvantaged», which are further put in opposition to the so-called «privileged» schools, creates a difference. Whereas in text D, systematic sorting, and clustering in five achievement levels are presented as based on clear dividing lines between performance entities, which define who belongs to a group sorted by ability.

Limitations

As regards any limitations of our analysis as outlined in the methodological section, only peer-reviewed articles were selected, which created a potential for bias (e.g., exclusion of grey literature). Furthermore, the text corpus included only a limited number of articles published in high-impact journals. This scarcity of articles and a general lack of renowned journals could be owed to our restrictive search strategy requiring many terms (i.e., gifted, inclusion, achievement, and synonyms). Even though all journals may belong to the field of education, the results might be influenced by the authors’ disciplinary field (e.g., psychology, counselling, or educational administration and policy). Additionally, more than a third of the articles refer to the US context, which can be seen as a further limitation. Future analysis should focus on a further investigation into an international text corpus considering articles in other languages than English. Also, the argumentation lines in the several contributions refer — some more clearly, some less — to divergent education systems at national levels, which have been included in the analysis but not presented in detail in this illustration of the contrasting texts. Despite these restrictions, the reference to a discourse-analytical approach has provided valuable insights into basic concepts such as giftedness, achievement, and inclusion by enabling their reconstruction. The readiness of this approach to question and challenge disciplinary-bound and taken-for-granted knowledge, which is regarded as one of its essential constitutive elements (Truschkat & Bormann, 2013), became evident during the analysis. Nevertheless, the research group faced the challenge of reflecting upon the context-bound nature of their own observer’s perspective point. This involves striking a delicate balance by distancing oneself from the disciplinary discourse in an inevitably artificial manner and posing a challenge to one’s positioning within the scientific community.

Conclusion

Overall, in the current discourse of research on giftedness, the reference to educational justice is prominent and likewise evident in the analysed scientific texts on giftedness, achievement, and inclusion. But, as an example for the entire text corpus, the contrasting discussion of the two texts on giftedness, achievement and inclusion shows that educational equity is understood hereby in distinct ways.

Text D mostly refers to a concept of distributive justice in terms of equal opportunities (Rawls, 1971; critically Walzer, 2006), which finds its primary consideration within the discussions on the «meritocratic principle» (Nerowski, 2018; critically Berkemeyer, 2018; Tenorth, 2020). Following this approach, it is considered fair for well-performing children to assume privileged positions in future society as they are autonomous young learners provided with equal opportunities as everybody else to perform well. On another side, this concept is criticized on the grounds that children are relatively dependent on schools developing learners’ autonomy rather than assuming it (e.g., Stojanov, 2011, p. 22; Pant, 2020; Cross & Cross, 2021). Contribution C refers explicitly to the concept of recognition justice (Honneth, 1992; Stojanov, 2011), led by a particular focus on pedagogical relations based on recognition in school. According to this approach, educational equity is mostly evident in the fact that recognizing individual learning processes opens adequate paths to self-realisation and personal development. In this regard, the contribution refers to the habitus theory by Bourdieu (1982).

Within the selected texts, there is a conspicuous tendency to problematise inclusion-related developments as a challenge for the promotion of giftedness or achievement orientation in schools. In some cases, reference is made to the concept of inclusion, while there is hardly any reference to inclusion-related theoretical developments. Instead, the focus shifts towards writings and approaches closely associated to special education, which is particularly significant in the context of diagnostic practices and categorial classifications as it suggests a parallelism between special education and gifted education, both of which seemingly rooted in a similar methodology and epistemology (Dell’Anna & Marsili, 2022). To put it differently, a link is established through the assumption of the specificity of «students having difficulties» on the one hand and «highly gifted students» on the other hand through the diagnostics targeting them. The latter not only rationalizes specific and exclusive programmes for the gifted (also) within a more inclusive school practice but also conceals the inequity-reinforcing impact of selectively supporting students perceived as particularly capable.

In conclusion, it becomes evident that various forms of «doing difference» regarding giftedness shape the discourse on giftedness, achievement, and inclusion. Contributions to the discourse that question the epistemological clarity of the concept of giftedness (Borland, 2021) or critically engage with policies of meritocracy in relation to giftedness education (Tomlinson, 2008) seem to be less impactful in the decade analysed here, as do conceptual contributions on open learning environments that respond to the individual talents of all children without any categorisation (Tomlinson, 1996), which can overall, be cautiously interpreted as a signal of discourse control in relation to the inclusion mandate. At the same time, critical debates in the social and cultural sciences question categorical and status-based approaches (Dai, 2016, 2018) and call for the integration of giftedness discourse into that of general education (Dai, 2022). In addition to discursive practices and critical reflections on the concept of giftedness as socially constructed (Borland, 2021; Marsili, 2022), this also concerns the pedagogical practices of diagnosis and the promotion of giftedness and achievement (Marsili, Dell’Anna, & Pellegrini, 2023). However, such debates seem to be conducted outside the established journals that could be found using our search criteria, so they appear to be conducted primarily outside the established discourses on gifted education during the last decade. Thus, our initial analyses may provide some indications about the recontextualisations of political agendas at the level of generating scientific knowledge, providing valuable insights for the further observation of debates on inclusion, achievement, and giftedness in relation to the meritocracy dispositif in different countries and educational systems (Tenret, 2014).

This is because the identified discourse dynamics not only safeguard specific approaches and positions, but also protect gifted education and its programmes in general. Therefore, deconstructive approaches and an «undoing» of race, class, and gender — as observed in parts of the discourse around inclusion and educational equity — pose a threat to giftedness research. In other words, inclusion is seemingly integrated into the discourse on gifted education but is subtly prevented from doing so.

References

Akbaba Y. & Bräu K. (2019), Lehrer*innen zwischen Inklusionsanspruch und Leistungsprinzip. In S. Ellinger & H. Schott-Leser (Eds.), Rekonstruktion sonderpädagogischer Praxis: Eine Fallsammlung für die Lehrerbildung, Opladen, Toronto, Verlag Barbara Budrich, pp. 165-184.

Ainscow M. & Sandill A. (2010), Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organisational cultures and leadership, «International Journal of Inclusive Education», vol. 14, n. 4, pp. 401-416.

Atkinson D. (1996), The «Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London», 1675-1975. A Sociohistorical Discourse Analysis, «Language in Society», vol. 25, n. 3, pp. 333-371.

Amrhein B. & Naraian S. (Eds.) (2022), Reading inclusion divergently: Articulations from around the world, Leeds, Emerald Publishing.

Baird J.A. (2009), Macro and micro influences on assessment practice, «Assessment in Education. Principles, Policy & Practice», vol. 16, n. 2, pp. 127-129.

Becker J., Arndt A.-K., Löser J.M., Urban M. & Werning R. (2020), Schule oder Wohlfahrtsverein? Positionierungen von Lehrkräften zur Leistungsbewertung im inklusiven Unterricht am Beispiel der Frage der (Nicht-)Versetzung, «Zeitschrift für Inklusion», vol. 4. https://www.inklusion-online.net/index.php/inklusion-online/article/view/575 (consulted on Nov 24th, 2023).

Berger P.L. & Luckmann T. (1977), Die gesellschaftliche Konstruktion der Wirklichkeit. Eine Theorie der Wissenssoziologie (5th ed.), Frankfurt am Main, Fischer.

Berkemeyer N. (2018), Über die Schwierigkeit, das Leistungsprinzip im Schulsystem gerechtigkeitstheoretisch zu begründen. Replik auf Christian Nerowski, «Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft», vol. 21, pp. 447-464.

Boaler J., William D. & Brown M. (2005), Students’ experiences of ability grouping-disaffection, polarisation and the construction of failure. In M. Nind, J. Rix, K. Sheehy & K. Simmons (Eds.), Curriculum and pedagogy in inclusive education. Values into practice, London, Routledge, pp. 41-55.

Boger M.-A. (2018), Implikationen des Dekategorisierungsdiskurses der Inklusionspädagogik für den Begabungsbegriff. In C. Kiso & J. Lagies (Eds.), Begabungsgerechtigkeit. Perspektiven auf stärkenorientierte Schulgestaltung in Zeiten von Inklusion, Wiesbaden, Springer VS, pp. 71-101.

Boger M.-A. & Textor A. (2016), Das Förderungs-Stigmatisierungs-Dilemma. Oder: Der Effekt diagnostischer Kategorien auf die Wahrnehmung durch Lehrkräfte. In B. Amrhein (Ed.), Diagnostik im Kontext inklusiver Bildung: Theorien, Ambivalenzen, Akteure, Konzepte, Bad Heilbrunn, Julius Klinkhardt, pp. 79-97.

Böker A. & Horvarth K. (2018), Ausgangspunkte und Perspektiven einer sozialwissenschaftlichen Begabungsforschung. In A. Böker & K. Horvarth (Eds.), Begabung und Gesellschaft. Sozialwissenschaftliche Begabung und Begabtenförderung, Wiesbaden, Springer, pp. 7-27.

Borland J.H. (1996), Gifted education and the threat of irrelevance, «Journal for the Education of the Gifted», vol. 19, pp. 129-147.

Borland J.H. (2021), The Trouble with Conceptions of Giftedness. In R.J. Sternberg & D. Ambrose (Eds.), Conceptions of Giftedness and Talent, Cham, Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 37-49.

Bourdieu P. (1982), Die feinen Unterschiede: Kritik der gesellschaftlichen Urteilskraft, Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp.

Bourdieu P. (2006), Wie die Kultur zum Bauern kommt, Hamburg, VSA.

Bourdieu P. & Passeron J.-C. (1971), Die Illusion der Chancengleichheit: Untersuchungen zur Soziologie des Bildungswesens am Beispiel Frankreichs, Stuttgart, Klett.

Breidenstein G. & Thompson C. (2014), Schulische Leistungsbewertung als Praxis der Subjektivierung. In C. Thompson, K. Jergus & G. Breidenstein (Eds.), Interferenzen: Perspektiven kulturwissenschaftlicher Bildungsforschung, Weilerswist, Velbrück, pp. 89-109.

Breuer F., Mey G. & Mruck K. (2011), Subjektivität und Selbst-/Reflexivität in der Grounded-Theory-Methodologie. In G. Mey & K. Mruck, Grounded Theory Reader, Wiesbaden, Springer, pp. 405-426.

Brunton J. & Thomas J. (2012), Information management in reviews. In D. Gough, S. Oliver & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews, Thousand Oaks, Sage, pp. 83-106.

Bublitz H. (2003), Diskurs, Bielefeld, transcript.

Coleman J.S., Campbell E.Q., Hobson C.J., McPartland J., Mood A.M., Weinfield F.D. & York R.L. (1966), Equality of Educational Opportunity, United States Government Printing Office.

Cross T.L. & Coleman L.J. (2005), School-Based Conception of Giftedness. In R.J. Sternberg & I.E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness, Cambridge, University Press, pp. 52-63.

Cross T.L. & Cross J.R. (2021), A school-based conception of giftedness: Clarifying roles and responsibilities in the development of talent in our public schools. In R.J. Sternberg & D. Ambrose (Eds.), Conceptions of Giftedness and Talent, Cham, Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 83-98.

Dai D.Y. (2016), Envisioning a new century of gifted education: The case for a paradigm shift. In D. Ambrose & R.J. Sternberg (Eds.), Giftedness and talent in the 21st century: Adapting to the turbulence of globalization, Rotterdam, Sense Publishers, pp. 45-63.

Dai D.Y. (2018), A century of quest for identity: A history of giftedness. In S. Pfeiffer (Ed.), The APA handbook on giftedness and talent, Washington, American Psychological Association Press, pp. 3-23.

Dai D.Y. (2022), Ten Changes That Will Render Gifted Education Transformational. In R.J. Sternberg, D. Ambrose & S. Karami (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Transformational Giftedness for Education, Cham, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 107-130.

Dell’Anna S. & Marsili F. (2022), Parallelismi, sinergie e contraddizioni nel rapporto tra Special Education, Gifted Education e Inclusive Education, «Form@re. Open Journal per la formazione in rete», vol. 22, n. 1, pp. 12-29.

Ebersold S., Watkins A., Óskarsdóttir E. & Meijer C. (2019), Financing Inclusive Education to Reduce Disparity in Education. Trends, Issues and Drivers. In M. Schuelka, C. Johnstone, G. Thomas & A. Artiles (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Inclusion and Diversity in Education, Los Angeles, Sage, pp. 232-248.

Edelstein W. (2006), Bildung und Armut. Der Beitrag des Bildungssystems zur Vererbung und zur Bekämpfung von Armut, »Zeitschrift für Soziologie der Erziehung und Sozialisation”, vol. 26, pp. 120-134.

El Khoury S. & Al-Hroub M. (2018), Definitions and conceptions of giftedness around the world. In S. El Khoury & M. Al-Hroub (Eds.), Gifted Education in Lebanese Schools. Integrating Theory, Research, and Practice, Cham, Springer International Publishing, pp. 9-38.

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2020), European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education. 2018/2019 Schoolyear Dataset Cross-Country Report, Odense, European Agency, https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/EASIE-2018-2019-cross-country-report. (consulted on Nov 24th, 2023).

Flashman J. (2012), Academic Achievement and Its Impact on Friend Dynamics, «Sociology of Education», vol. 85, pp. 61-80.

Flick U. (2007), Designing Qualitative Research, London, Sage.

Foucault M. (1977), Überwachen und Strafen. Die Geburt des Gefängnisses, Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp.

Grek S. (2009), Governing by numbers. The PISA «effect» in Europe, «Journal of Education Policy», vol. 24, pp. 23-37.

Gellert U. (2013), Heterogen oder hierarchisch? Zur Konstruktion von Leistung im Unterricht. In J. Budde (Ed.), Unscharfe Einsätze. (Re-)Produktion von Heterogenität im schulischen Feld, Wiesbaden, Springer, pp. 211-227.

Gomolla M. (2012), Leistungsbeurteilung in der Schule. Zwischen Selektion und Förderung, Gerechtigkeitsanspruch und Diskriminierung. In S. Fürstenau & M. Gomolla (Eds.), Migration und schulischer Wandel: Leistungsbeurteilung, Wiesbaden, Springer, pp. 25-50.

Gunnarsson B.L. (2014), On the sociohistorical construction of scientific discourse. In B.L. Gunnarsson P. Linell & B. Nordberg (Eds.), The construction of professional discourse, London, Routledge, pp. 99-126.

Hillmert S. & Jacob M. (2010), Selections and social selectivity on the academic track. A life-course analysis of educational attainment in Germany, «Research in Social Stratification and Mobility», vol. 28, pp. 59-76.

Hollingworth L.S. (1926), Gifted children: Their nature and nurture, New York, NY, Macmillan.

Honneth A. (1992), Kampf um Anerkennung. Zur moralischen Grammatik sozialer Konflikte, Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp.

Hooks B. (2000), Where we stand. Class matters, London, Routledge.

Hopf C. (2004), Forschungsethik und qualitative Forschung. In U. Flick, E. von Kardorff & I. Steinke (Eds.), Qualitative Forschung: Ein Handbuch, Hamburg, Rowohlt, pp. 589-600.

Horvarth K. (2018), «Wir können fördern, wir können fordern, aber begaben können wir nicht». Pädagogische Begabungsunterscheidungen im Kontext sozialer Ungleichheiten. In A. Böker & K. Horvarth (Eds.), Begabung und Gesellschaft: Sozialwissenschaftliche Perspektiven auf Begabung und Begabtenförderung, Wiesbaden, Springer, pp. 239-262.

International Panel of Experts for Gifted Education/iPEGE (2009), Professionelle Begabtenförderung. Empfehlungen zur Qualifizierung von Fachkräften in der Begabtenförderung, Österreichisches Zentrum für Begabtenförderung und Begabungsforschung, http://www.ipege.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/iPEGE_Broschuere.pdf (consulted on Nov 24th, 2023).

Jimerson S.R., Burns M.K. & Van Der Heyden A. (2016), Handbook of Response-to-Intervention. The Science and Practice of Multi-Tiered Systems of Support, New York, Springer.

Kelle H. & Tervooren A. (Eds.) (2008), Ganz normale Kinder. Heterogenität und Standardisierung kindlicher Entwicklung, Wiesbaden, VS.

Keller R. (2003), Diskursforschung. Eine Einführung für SozialwissenschaftlerInnen, Opladen, Leske and Budrich.

Keller R. (2005), Wissenssoziologische Diskursanalyse als interpretative Analytik. In R. Keller, A. Hirseland, W. Schneider & W. Viehöver (Eds.), Die diskursive Konstruktion von Wirklichkeit: Zum Verhältnis von Wissenssoziologie und Diskursforschung, Konstanz, UVK, pp. 49-76.

Keller R. (2011a), Diskursforschung. Eine Einführung für SozialwissenschaftlerInnen, Wiesbaden, Springer.

Keller R. (2011b), Das Interpretative Paradigma, Wiesbaden, Springer.

Keller R. (2013). Doing Discourse Research. An Introduction for Social Scientists, London, Sage.

Kollender E. (2016), Die sind nicht unbedingt auf Schule orientiert. Formationen eines‚ racial neoliberalism, an innerstädtischen Schulen Berlins, «Movements», vol. 2, n. 1, pp. 39-64.

Köpfer A., Powell J. & Zahnd R. (2021), Entwicklungslinien internationaler und komparativer Inklusionsforschung. In A. Köpfer, J. Powell & R. Zahnd (Eds.), Globale, nationale und lokale Perspektiven auf Inklusive Bildung, Opladen, Barbara Budrich, pp. 11-39.

Kottmann B. (2022), Der Übergang von der Grundschule zur weiterführenden Schule als (Soll)Bruchstelle des Gemeinsamen Lernens? In B. Schimek, G. Kremsner, M. Proyer, R. Grubich F. Paudel and R. Grubich-Müller (Eds.), Grenzen. Gänge. Zwischen. Welten. Kontroversen-Entwicklungen-Perspektiven der Inklusionsforschung, Bad Heilbrunn, Klinkhardt, pp. 165-172.

Kramer R.-T. (2017), Habitus und kulturelle Passung. In M. Rieger-Ladich & C. Grabau (Eds.), Pierre Bourdieu. Pädagogische Lektüren, Wiesbaden, Springer, pp. 183-205.

Machold C. & Wienand C. (2021), Die Herstellung von Differenz in der Grundschule, Weinheim Basel, Beltz.

Mannheim K. (1980), Strukturen des Denkens, Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp.

Margolin L. (2018), Gifted Education and the Mathew effect. In A. Böker & K. Horvarth (Eds.), Begabung und Gesellschaft. Sozialwissenschaftliche Perspektiven auf Begabung und Begabtenförderung, Wiesbaden, Springer, pp. 165-182.

Marsili F. (2022). Per un nuovo paradigma di plusdotazione: tra relazione, bene comune e meritocrazia. In M. Casucci (Ed.), Relazioni e bene comune, Perugia, Pièdimosca, pp. 89-105.

Marsili F., Dell’Anna S. & Pellegrini M. (2023), Giftedness in inclusive education: A systematic review of research, «International Journal of Inclusive Education», https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2023.2190330.

Migliarini V., D’Alessio S. & Bocci F. (2020), SEN Policies and migrant children in Italian schools: Micro-exclusions through discourses of equality, «Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education», vol. 41, n. 6, pp. 887-900.

Nerowski C. (2018), Leistung als Kriterium von Bildungsgerechtigkeit, «Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft», vol. 21, pp. 441-464.

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) (2015), The ABC of Gender Equality in Education: Aptitude, Behaviour, Confidence. http://www.oecd.org/pisa/keyfindings/pisa-2012-results-gender.htm (consulted on Nov 24th, 2023).

Pant H.-A. (2020), Notengebung, Leistungsprinzip und Bildungsgerechtigkeit. In S.-I. Beutel & H.-A. Pant (Eds.), Lernen ohne Noten. Alternative Konzepte der Leistungsbeurteilung, Stuttgart, Kohlhammer, pp. 22-58.

Pereyra M.A., Kotthoff H.-G. & Cowen R. (Eds.) (2011), PISA Under Examination. Changing Knowledge, Changing Tests, and Changing Schools, Rotterdam, SensePublishers.

Popkewitz T.S. (2011), PISA. Numbers, standardizing conduct, and the alchemy of school subjects. In M. Pereyra, H.-G. Kotthoff & R. Cowen (Eds.), PISA Under Examination: Changing Knowledge, Changing Tests, and Changing Schools, Rotterdam, SensePublishers, pp. 31-46.

Powell J. (2018), Inclusive Education. Entwicklungen im internationalen Vergleich. In T. Sturm & M. Wagner-Willi (Eds.), Handbuch schulische Inklusion, Opladen, Budrich, pp. 126-141.

Powell P.M. & Haden T. (1984), The intellectual and psychosocial nature of extreme giftedness, «Roeper Review», vol. 6, pp. 131-133.

Rawls J. (1971), A theory of justice, Harvard, Harvard University Press.

Reh S. & Ricken N. (2018), Leistung als Paradigma. Zur Entstehung und Transformation eines pädagogischen Paradigmas, Wiesbaden, Springer.

Renzulli J.S. & Reis S.M. (2021), The Schoolwide Enrichment Model. A How-To Guide for Talent Development, Waco, Prufrock Press.

Riefling M. & Koop C. (2018), «Elitekind» und «Kopftuchmädchen». Perspektiven der Begabungsförderung im Lichte der Rationalen Pädagogik. In A. Böker & K. Horvarth (Eds.), Begabung und Gesellschaft: Sozialwissenschaftliche Perspektiven auf Begabung und Begabtenförderung, Wiesbaden, Springer, pp. 263-284.

Ricken N. (2018), Konstruktionen der Leistung. Zur (Subjektivierungs-)Logik eines Konzepts. In S. Reh & N. Ricken (Eds.), Leistung als Paradigma: Zur Entstehung und Transformation eines pädagogischen Paradigmas, Wiesbaden, Springer, pp. 43-60.

Sandri P. (2014), Integration and inclusion in Italy: Towards a special pedagogy for inclusion, «ALTER - European Journal of Disability Research», vol. 8, pp. 92-104.

Schäfer A. (2018), Das problematische Versprechen einer Leistungsgerechtigkeit. In T. Sansour, O. Musenberg & J. Riegert (Eds.), Bildung und Leistung: Differenz zwischen Selektion und Anerkennung, Bad Heilbrunn, Klinkhardt, pp. 11-58.

Staiger A. (2018), Whiteness as Giftedness. Racial Formation at an Urban High School. In A. Böker & K. Horvarth (Eds.), Begabung und Gesellschaft: Sozialwissenschaftliche Begabung und Begabtenförderung, Wiesbaden, Springer, pp. 207–238.

Stern W. (1916), Psychologische Begabungsforschung und Begabungsdiagnose. In P. Petersen (Ed.), Der Aufstieg der Begabten: Vorfragen: Deutscher Ausschuss für Erziehung und Unterricht, Leipzig, Teubner, pp. 105-120.

Sternberg R.J. (2003), Wisdom, intelligence, and creativity, synthesized, New York, Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg R.J. (2019), Is Gifted Education on the right Path? In B. Wallace, D. Sisk & J. Senior (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Gifted and Talented Education, Los Angeles, Sage, pp. 5-S18.

Stojanov K. (2011), Bildungsgerechtigkeit. Rekonstruktionen eines umkämpften Begriffs, Wiesbaden, Springer.

Strauss A.L. (1987), Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists, New York, Cambridge University Press.

Strauss A.L. & Corbin J. (1996), Grounded Theory. Grundlagen qualitativer Sozialforschung, Weinheim, Psychologie-Verlag-Union.

Strübing J. (2014), Zur sozialtheoretischen und epistemologischen Fundierung eines pragmatischen Forschungsstils, Wiesbaden, Springer.

Tenorth H.-E. (2020), Über die Schwierigkeiten der Pädagogik, über Leistung und Gerechtigkeit im Schulsystem zu reden. Eine Meta-Kritik zu Berkemeyers Nerowski-Kritik, «Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft», vol. 23, pp. 439-449.

Tenret E. (2014), La meritocrazia a scuola, attraverso la scuola. Il caso italiana in prospettiva comparata, «Quaderni di Sociologia», vol. 64, pp. 45-71.

Terman L.-M. (1916), The Measurement of Intelligence. An Explanation of and a Complete Guide for the Use of the Stanford Revision and Extension of the Binet-Simon Intelligence Scale, Boston, Mifflin.

Tomlinson C.A. (1996), Good Teaching for One and All: Does Gifted Education Have an Instructional Identity?, «Journal for the Education of the Gifted», vol. 20, n. 2, pp. 155-174.

Tomlinson S. (2008), Gifted, Talented and High Ability: Selection for Education in a One-Dimensional World, «Oxford Review of Education», vol. 34, n. 1, pp. 59-74.

Truschkat I. & Bormann I. (2013), Das konstruktive Dilemma einer Disziplin. Sondierungen erziehungswissenschaftlicher Zugänge zur Diskursforschung, «Zeitschrift für Diskursforschung», vol. 1, pp. 88-111.

United Nations (2006), Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convention_accessible_pdf.pdf (consulted on Nov 24th, 2023).

United Nations (n. d.), 17 Goals to Transform Our World. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (consulted on January 14th, 2024).

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (1994), The Salamanca statement and framework for action on special needs education, New York, United Nations.

van Essen F. (2013), Soziale Ungleichheit, Bildung und Habitus, Wiesbaden, Springer.

Van de Werfhorst H.G. & Mijs J.J.B. (2010), Achievement Inequality and the Institutional Structure of Educational Systems. A comparative perspective, «The Annual Review of Sociology», vol. 36.

Viehöver W., Keller R. & Schneider W. (2013), Diskurs-Sprache-Wissen: Ein problematischer Zusammenhang? In W. Viehöver, R. Keller & W. Schneider (Eds.), Diskurs-Sprache-Wissen. Interdisziplinäre Diskursforschung, Wiesbaden, Springer, pp. 7-19.

Wagner-Willi M., Sturm T., Wagener B. & Elseberg A. (2018), Herstellung und Bearbeitung von Differenz im Fachunterricht der Sekundarstufe I — eine Vergleichsstudie zu Unterrichtsmilieus in inklusiven und exklusiven Schulformen, https://irf.fhnw.ch/bitstream/handle/11654/27462/Abschlussbericht_snf_06-18_geku%cc%88rzt.pdf?sequence=1 (consulted on Nov 24th, 2023).

Walzer M. (2006), Sphären der Gerechtigkeit: Ein Plädoyer für Pluralität und Gleichheit, Frankfurt, Campus.

Weigand G. (2011), Geschichte und Herleitung eines pädagogischen Begabungsbegriffs. In A. Hackl, O. Steenbuck & G. Weigand (Eds.), Werte schulischer Begabtenförderung: Begabungsbegriff und Werteorientierung, Frankfurt am Main, Karg Stiftung, pp. 48-54.

Weigand G. (2021), Begabung, Bildung und Person. In V. Müller-Oppliger & G. Weigand (Eds.), Handbuch Begabung, Weinheim, Basel, Beltz, pp. 46-64.

1 Simone Seitz è responsabile della sezione Giftedness e rendimento scolastico in relazione all’agenda dell’inclusione, Secondo test esemplare (pubblicazione D) e della Conclusione; Michaela Kaiser della sezione Primo testo esemplare (pubblicazione C), Discussione generale dei due testi contrastanti e Limitazioni; Petra Auer dell’abstract e della sezione Approccio metodologico e progettazione; Rosa Bellacicco della sezione Argomentazione metodologica e Limitazioni.

2 Libera Università di Bolzano, Facoltà di Scienze della Formazione.

3 Università Carl von Ossietzky di Oldenburg, Istituto per l’arte e la cultura visiva.

4 Libera Università di Bolzano, Facoltà di Scienze della Formazione.

5 Università di Torino, Dipartimento di Filosofia e Scienze dell’Educazione.

6 Simone Seitz is responsible for section Giftedness and achievement in relation to the agenda of inclusion, Second exemplary test (publication D), and Conclusion; Michaela Kaiser for section First exemplary text (publication C), Overall discussion of the two constrasting texts, and Limitations; Petra Auer for the abstract and section Methodological approach and design, and Rosa Bellacicco for section Methodological argumentation and Limitations.

7 Free University of Bolzano, Faculty of Educational Sciences.

8 Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg, Institute for Art and Visual Culture.

9 Free University of Bolzano, Faculty of Educational Sciences.

10 University of Turin, Department of Philosophy and Educational Sciences.

11 At the same time, the idea of retardation and the idea of specific concepts and programs for children with that diagnosis became established (Kelle & Tervooren, 2008).

12 As search terms, we used gifted students OR gifted OR gifted children OR giftedness OR talent OR gifted and talented OR gifted education as mandatory terms in the abstract AND inclusion OR inclusive education OR mainstream*ing AND achievement OR performance OR success OR outcomes as mandatory terms in the text.

13 Specifically, in line with the methodological approach, we selected the articles based on theoretical assumptions with the aim to include those which are profitable concerning the research question.

14 The French term dispositif relates to «[…] the material and ideational infrastructure, i.e., the bundle of measures, regulations, artefacts, by means of which a discourse is (re)produced and achieves effects (e.g., laws, codes of behaviour, buildings, measuring devices)» and is often translated by apparatus (Keller, 2013, p. 73).

15 To ensure the anonymity of the texts and their author(s), the journals are not listed here. The full list can be obtained from the authors of this article.

16 To allow a classification of the listed Journals, the highest ranked Journal in the area of education has an SJR-value of 5.969.

17 Both SJR and H-Index have been retrieved from https://www.scimagojr.com/

18 SJR takes into account the prestige of the citing journal; citations are weighted to reflect whether they come from a journal with a high or low SJR.

Vol. 23, Issue 1, February 2024