© Edizioni Centro Studi Erickson, Trento, 2023 — Counseling

Vol. 16, n. 1, febbraio 2023

strumenti

Workplace Relational Civility Scale

Proprietà psicometriche della versione spagnola

Francisco Rodríguez-Cifuentes1

Sommario

Il presente manoscritto ha lo scopo di analizzare le proprietà psicometriche della scala Workplace Relational Civility (WRC) adattata al contesto spagnolo. Duecentotrentuno individui hanno partecipato allo studio. Dopo aver verificato l’adeguatezza dei dati, sono state condotte una serie di analisi fattoriali confermative. Il modello bifattoriale (corrispondente alle sottoscale originarie: io verso gli altri e gli altri verso di me), mantenendo la struttura tridimensionale interna, presenta il fit migliore. Il questionario ha mostrato anche buoni livelli di affidabilità e validità concorrente. Visti i risultati, la versione spagnola della WRC è uno strumento valido e attendibile per i lavoratori spagnoli.

Parole chiave

Civiltà relazionale sul posto di lavoro, Proprietà psicometriche, WRC, Contesto spagnolo.

INSTRUMENTS

The Workplace Relational Civility Scale

Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version

Francisco Rodríguez-Cifuentes2

Abstract

The present manuscript aims to analyse the psychometric properties of the Workplace Relational Civility (WRC) scale adapted to the Spanish context. Two hundred and thirty-one individuals participated in the study. After verifying data adequacy, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses. The bifactorial model (corresponding to the original subscales: me with others and others with me), maintaining the inner three-dimensional structure, presents the best fit. The questionnaire also showed good levels of reliability and concurrent validity. Given the results, the Spanish version of the WRC is a valid and reliable instrument for Spanish workers.

Keywords

Workplace relational civility, Psychometric properties, WRC, Spanish context.

The constantly changing labour market requires a permanent adaptation to new situations. Globalisation has impacted employment, and although it provides new opportunities, it also provokes undesirable outcomes, such as increased workplace incivility (Sleem & Seada, 2017). People and organizations should face this stressful context by going beyond the traditional economic aim of survival. Taking advantage of one’s capacities and developing healthy businesses appear as objectives that encompass the positive psychology perspective (Adkins, 1999) and official recommendations and guidelines (World Health Organization, 2007).

From this fostering vision, people deserve to live with the possibility of improving themselves and their surrounding world. Several theories have emerged from the enormous positive psychology framework which study and clarify the factors involved in this pursuit of a better world; for instance, the Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development (Di Fabio, 2017) or the Humanitarian Work Psychology (Carr et al., 2012).

The increasing research lines of those topics have facilitated the development of different constructs. For example, human capital sustainability leadership (Di Fabio & Peiró, 2018), organizational support (Eisenberger et al., 1990), organizational citizenship behaviour (Podsakoff et al., 1990), workplace civility (Di Fabio, 2015c) or workplace relational civility (Di Fabio & Gori, 2016). All of those concepts underline the critical role that social relationships have in organizational success.

Workplace relational civility (WRC) refers to a specific relational style at work, which is «characterised by respect and concern for oneself and others, interpersonal sensitivity, personal education, and kindness toward others. It also includes civil behaviours such as treating others with dignity and respecting social norms to facilitate peaceful and productive cohabitation» (Di Fabio & Gori, 2016, p. 2). The authors propose a three-dimensional structure, thus: (i) relational decency (RD), which refers to desirable relationship characteristics (e.g. to be based on respect for oneself and other parties); (ii) relational culture (RC), which emphasises politeness and good manners in relationships; and; (iii) relational readiness (RR), which comprises the abilities needed to develop and maintain healthy relationships. This comprehensive focus on organizational relationships gives this construct a non-negligible use potential compared with others like emotional intelligence (Di Fabio et al., 2016).

Since its appearance, researchers have taken into account this variable, and they have investigated its implications in organizational contexts. In this sense, literature highlights the relationships between WRC and certain personality traits, incrementing their predictive capacity to explain variables like human capital sustainability leadership (Di Fabio & Gori, 2016) or acceptance of change, life satisfaction, and meaning of life (Di Fabio et al., 2016).

Due to its broad relationships with other concepts, WRC has appeared as a variable in multiple pieces of research. For example, Gori & Topino (2020) find that perceiving colleagues as civil towards oneself significantly mediated the relationship between predisposition to change and job satisfaction. Despite all these promising results, the connections may be complex and more research should be undertaken. For instance, Seok et al. (2022) recently pointed out the positive and significant relationship between positive relation management and WRC, but only in its sub-dimension of caring. Furthermore, change-seeking seemed to harm this relationship.

In sum, WRC appears to be a vital variable in fostering healthy organizations and sustainable development. Thus, according to Palazzeschi et al. (2018), people who obtain high scores on entrepreneurism, leadership and professionalism (HELP) appear to have a higher perception of WRC and flourishing scores.

In agreement with the aforementioned results, WRC could be understood as a psychological resource for hedonic and eudaimonic well-being (Di Fabio et al., 2016), and also in an academic context (Di Fabio & Kenny, 2018). One encouraging implication is the one referred to by Reed et al. (2019), stating that we can teach civility and integrate it into the organizational culture, endowing students and workers with relationship-building competency.

Unfortunately, a validated Spanish version which measures this construct is not available yet. With this objective, this paper aims to analyse the psychometric properties of the WRC questionnaire (Di Fabio & Gori, 2016) in the Spanish context. The original instrument is divided into two specular sections (Part A – Me with others; Part B – Others with me) and shows the three-dimensional structure mentioned above. The measure’s reliability and validity (convergent and divergent) makes it a great starting point for our research.

Method

Participants

A total of 231 workers from Spain participated in the study (44.6% females and 55.4% males). The mean age was 42.4 years (SD = 11.7). Regarding the professional sector, the participants worked in diverse fields such as education or healthcare (26.4%), manufacturing (29.8%) or in the telecommunications industry (10.8%).

Measures

Workplace Relational Civility. The original Italian version of the WRC (Di Fabio & Gori, 2016) is a self-report mirror instrument comprising 26 items (Part A: Me with others – colleagues and superiors –, and Part B = Others with me; 13 items each), displayed in a Likert-type scale. The points ranged from 1 = not at all to 5 = a great deal. The scale validation reported a three-dimensional structure: relational decency (4 items, example: «I respected others’ opinions»), relational culture (4 items, example: «I’ve been respectful to others»), and relational readiness (5 items, example: «I’ve been attentive to others’ needs»). The reliability was good for all the dimensions for both parts (α > 0.75).

Flourishing. The Flourishing Scale (Diener et al., 2010; Spanish Version by Pozo Muñoz et al., 2019) comprises eight items, such as «I am optimistic about my future». The response format is a Likert scale with five possibilities (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree). The Spanish version reported Cronbach’s alpha coefficients above 0.85 for Spanish and Colombian samples; similar to our own results (α > 0.89).

Satisfaction with Life. To measure this variable, we used the Spanish adaptation (Atienza et al., 2000) of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (Diener et al., 1985). The instrument presents a Likert-type format, with five response options instead of the original seven. They range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. An example of the items is, «In most ways my life is close to my ideal». The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the SWLS Spanish version was 0.84. The scale reliability in our sample was even better (α > 0.89).

Workplace Incivility. This concept was measured using the Incivility Scale (Matthews & Ritter, 2016; Spanish Version by Di Marco et al., 2018), which comprises four items. One example of them is «(a co-worker or supervisor…) paid little attention to your statements or showed little interest in your opinions». The scale is Likert-type, with responses that range from 1 (never) to 5 (many times). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient reported good internal consistency (α = 0.75); we also obtained this good result (α > 0.89).

Procedure

The research was developed in two phases. In the first one, we implemented a back translation method. Two translators carried out a direct conceptual translation of the original Italian language version of the WRC instrument. Then, two translators did the inverse process and translated the scale into Italian. There were no significant differences, and all the translators determined a consensus for the Spanish version.

Later, data were collected by convenience sampling. Participants completed all the given questionnaires. Researchers explained the aims of the data collection and the correct way of answering the questions. Participation was voluntary, and privacy and anonymity conditions were assured, according to the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013). Participants could withdraw and ask about any aspect of the research.

Data Analysis

The factor structure of the Spanish version of the WRC was investigated by means of a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) through RStudio 2022.07.0 for Windows. The Packages Lavaan 0.6-9, SemPlot 1.1.2 and Psyhc 2.2.5 were implemented. Prior to running the main analyses, skewness and kurtosis were inspected for each item of the WRC (table 1). Since all the item values are in the range (−1, 1) (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007), the CFA was implemented by applying maximum-likelihood (ML) estimation.

Table 1

The Spanish Version of the Workplace Relational Civility: Item statistics (n = 231).

|

WRC item |

N |

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

|

A1 |

231 |

4.01 |

0.88 |

1 |

5 |

-0.64 |

-0.08 |

|

A2 |

231 |

4.17 |

0.77 |

2 |

5 |

-0.59 |

-0.24 |

|

A3 |

231 |

4.29 |

0.74 |

2 |

5 |

-0.91 |

0.62 |

|

A4 |

231 |

4.16 |

0.83 |

1 |

5 |

-0.86 |

0.50 |

|

A5 |

231 |

4.36 |

0.71 |

2 |

5 |

-0.88 |

0.32 |

|

A6 |

231 |

4.39 |

0.67 |

2 |

5 |

-0.81 |

0.30 |

|

A7 |

231 |

4.32 |

0.76 |

2 |

5 |

-0.97 |

0.51 |

|

A8 |

231 |

4.23 |

0.76 |

1 |

5 |

-0.89 |

0.10 |

|

A9 |

231 |

4.25 |

0.74 |

1 |

5 |

-0.76 |

0.65 |

|

A10 |

231 |

4.29 |

0.67 |

2 |

5 |

-0.50 |

-0.33 |

|

A11 |

231 |

4.10 |

0.77 |

2 |

5 |

-0.53 |

-0.16 |

|

A12 |

231 |

4.06 |

0.77 |

2 |

5 |

-0.33 |

-0.64 |

|

A13 |

231 |

3.97 |

0.81 |

1 |

5 |

-0.58 |

0.50 |

|

B1 |

231 |

3.88 |

0.81 |

1 |

5 |

-0.37 |

0.20 |

|

B2 |

231 |

3.83 |

0.92 |

1 |

5 |

-0.61 |

0.27 |

|

B3 |

231 |

3.81 |

0.94 |

1 |

5 |

-0.56 |

-0.09 |

|

B4 |

231 |

3.89 |

0.87 |

2 |

5 |

-0.43 |

-0.47 |

|

B5 |

231 |

3.96 |

0.84 |

1 |

5 |

-0.77 |

0.96 |

|

B6 |

231 |

3.97 |

0.85 |

1 |

5 |

-0.79 |

0.93 |

|

B7 |

231 |

3.93 |

0.83 |

1 |

5 |

-0.43 |

-0.10 |

|

B8 |

231 |

3.75 |

0.92 |

1 |

5 |

-0.69 |

0.71 |

|

B9 |

231 |

3.54 |

1.04 |

1 |

5 |

-0.52 |

0.03 |

|

B10 |

231 |

3.59 |

1.05 |

1 |

5 |

-0.71 |

0.21 |

|

B11 |

231 |

3.40 |

0.98 |

1 |

5 |

-0.37 |

0.24 |

|

B12 |

231 |

3.44 |

0.97 |

1 |

5 |

-0.40 |

0.00 |

|

B13 |

231 |

3.30 |

0.98 |

1 |

5 |

-0.24 |

-0.17 |

Note. WRC: Workplace Relational Civility; A = Part; B = Part B.

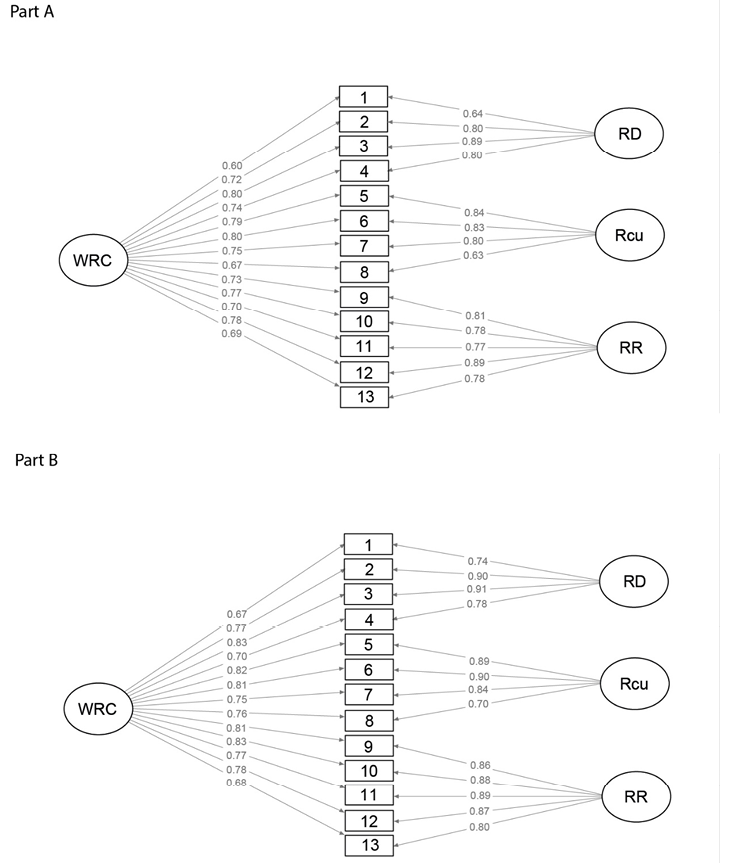

Three models were tested for both part A and part B of the WRC construct. The first was a three-factor correlated model, in which each item loaded on its corresponding factor. The three factors were mutually correlated (RR at work, RC at work, and RD at work). The second model was the higher-order model, in which items loaded on their respective factor, and the three factors regressed onto a higher-order factor. The third model is the bifactor model, i.e. items are simultaneously regressed on their respective three factors and onto a WRC factor.

Models were compared considering the following fit indices: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Comparative Fit Index (values greater than 0.90 show a good fit); the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (values lower than 0.08 show good fit) (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). The reliability of the Spanish version of the WRC was analysed by calculating Cronbach’s alphas. Values greater than 0.70 were considered acceptable (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Convergent and concurrent validities were inspected through Pearson correlations between WRC and FS, SWLS, and WIS. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Table 2 reports the results of the fit measures of the three tested models. The two-bifactor model showed the best fit with all acceptable fit indexes for WRC part A and WRC part B. Differently, the three-factor model, and the higher-order model showed unacceptable fit indexes for both part A and part B (table 2).

Table 2

The Spanish Version of the Workplace Relational Civility: Confirmatory Factor Analysis - Goodness of Fit indices (n = 231).

|

Model |

Fit Indices |

|||

|

χ2(df) |

CFI |

TLI |

RMSEA [95%CI] |

|

|

Correlational Part A |

258(62)*** |

0.912 |

0.889 |

0.113 [0.099-0.128] |

|

Higher order Part A |

258(62)*** |

0.912 |

0.889 |

0.113 [0.099-0.128] |

|

Bifactor Part A |

118(48)*** |

0.967 |

0.947 |

0.071 [0.051 -0.087] |

|

Correlational Part B |

274(62)*** |

0.921 |

0.901 |

0.122 [0.107 – 0.137] |

|

Higher order Part B |

274(62)*** |

0.921 |

0.901 |

0.122 [0.107- 0.137] |

|

Bifactor Part Part B |

116(48)*** |

0.975 |

0.959 |

0.078 [0.060-0.097] |

Note. Part A: Me with others; Part B: Others with me; WRC: Workplace Relational Civility; CFI: Comparative Fit Index; TLI: Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation. *** p < .001

Standardised β of the two-bifactor model of the WRC were reported in the path diagram shown in figure 1.

Figure 1

The Spanish Version of the Workplace Relational Civility: Path diagram of bifactor models of Part A and Part B (n = 231).

Note. Part A: Me with others; Part B: Others with me; WRC: Workplace Relational Civility; RD: Relational decency at work; RC: Relational culture at work; RR: relational readiness at work.

Table 3 reports the Cronbach alpha calculated for the bifactor measurement model of parts A and B of the WRC. Two Cronbach alphas were computed for the overall scores of part A and part B, and three Cronbach alphas were also calculated for each of the three factors of both. For the total score, Cronbach’s alphas were 0.94 for part A and 0.95 for part B. Each factor of the two parts showed excellent values of reliability ranging from 0.85 (Relational Culture part A) to 0.95 (Relational Readiness part B).

Table 3

The Spanish Version of the Workplace Relational Civility: Cronbach’s alphas for the two-bifactor measurement model (n = 231).

|

WRC Subscale |

Cronbach’s a |

|

Part A |

0.94 |

|

Relational decency |

0.86 |

|

Relational culture |

0.85 |

|

Relational readiness |

0.90 |

|

Part B |

0.95 |

|

Relational decency |

0.89 |

|

Relational culture |

0.93 |

|

Relational readiness |

0.95 |

Note. Part A: Me with others; Part B: Others with me; WRC: Workplace Relational Civility.

Convergent validity and concurrent validity were found to be good, showing a positive association of WRC with SLWS and FS, whereas WRC showed negative associations with WI (Table 4).

Discussion

The paper’s primary purpose was to analyse the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the WRC (Di Fabio & Gori, 2016), in order to have an adequate measure available in the Spanish context.

Through the CFA, we confirmed the instrument’s mirror shape besides its three-dimensional structure (i.e. relational decency, relational culture and relational readiness). According to the Italian validation of the scale, the concurrent validity of the WRC is coherent with literature: positive relationships with satisfaction with life and flourishing and negative with workplace incivility (Di Fabio & Gori, 2016). Additionally, the reliability of the WRC is good regarding Cronbach’s Alpha.

Table 4

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

|

1. FS |

— |

|||||||||

|

2. SWLS |

0.72*** |

— |

||||||||

|

3. WIS |

-0.28*** |

-0.29*** |

— |

|||||||

|

4. Total Part A |

0.57*** |

0.36*** |

-0.07 |

— |

||||||

|

5. RD Part A |

0.49*** |

0.34*** |

-0.04 |

0.88*** |

— |

|||||

|

6. RC Part A |

0.51*** |

0.32*** |

-0.06 |

0.92*** |

0.76*** |

— |

||||

|

7. RR Part A |

0.54*** |

0.32*** |

-0.09 |

0.90*** |

0.64*** |

0.75*** |

— |

|||

|

8. Total Part A |

0.46*** |

0.41*** |

-0.28*** |

0.51*** |

0.47*** |

0.43*** |

0.47*** |

— |

||

|

9. RD Part A |

0.43*** |

0.38*** |

-0.22*** |

0.51*** |

0.49*** |

0.45*** |

0.45*** |

0.87*** |

— |

|

|

10. RC Part A |

0.47*** |

0.40*** |

-0.27*** |

0.47*** |

0.45*** |

0.43*** |

0.40*** |

0.91*** |

0.78*** |

— |

|

11. RR Part A |

0.36*** |

0.34*** |

-0.27*** |

0.41*** |

0.36*** |

0.31*** |

0.42*** |

0.90*** |

0.62*** |

0.72*** |

The Spanish Version of the Workplace Relational Civility: correlations among the two parts of WRC and FS, SWLS, and WIS (n = 231).

Note. FS: Flourishing Scale; SWLS: WIS: Workplace Incivility Scale; RD: Relational decency at work; RC: Relational culture at work; RR: relational readiness at work. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Given those results, this research helps provide a valid measure in Spanish and proves the construct’s theoretical strength by finding the same internal structure. Future research should consider possible regional differences and adapt the questionnaire to broader Spanish-speaking populations. Also, it would be beneficial to test the construct validity with other related concepts like organizational citizenship behaviour.

The potential uses of this measure fit with a primary prevention perspective (Di Fabio et al., 2017; Hage et al., 2007), in which improving the social scenario in workplaces becomes a primary aim. Given the breadth of organizational realities, WRC could be applied to multiple professional sectors, e.g. banking (Zayas-Ortiz et al., 2015) or healthcare (Atluntas & Baykal, 2010). In those fields, particular and general problems may arise, and WRC could be an effective tool to prevent undesirable outcomes such as sexual harassment (Tan et al., 2020). Even though WRC shows relationships with personality traits, it can be considered a resource and is, therefore, developable. At the workplace, we face the challenge of building a harmonious organizational structure and maintaining that structure as a corporate value (Reed et al., 2019). Everyone in the organization is responsible for this demanding task, and WRC comprises this requirement, making the way workers affect their surroundings and vice versa explicit. This perspective is in agreement with the prominent voices that say that building healthy and sustainable organizations and businesses are both workers’ and organizations’ jobs (Corbett, 2004; Lowe, 2010).

References

Adkins, J. A. (1999). Promoting organisational health: The evolving practice of occupational health psychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 30(2), 129-137. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.30.2.129

Altuntas, S., & Baykal, U. (2010). Relationship between nurses’ organizational trust levels and their organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 42(2), 186-194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01347.x

Browne, M.W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit in Bollen. In K.A & J.S. Long (Eds), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136-162). London: Sage.

Atienza, F. L., Pons, D., Balaguer, I., & Garcia-Merita, M. L. (2000). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la Vida en adolescentes [Psychometric properties of Satisfaction with Life Scale in adolescents]. Psicothema, 12, 331-336.

Carr, S. C., MacLachlan, M., & Furnham, A. (2012). Humanitarian Work Psychology. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Corbett, D. (2004). Excellence in Canada: Healthy Organizations - Achieve results by acting responsibly. Journal of Business Ethics, 55(2), 125-133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-004-1896-8

Di Fabio, A. (2017). The Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development for well-being in organisations. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1534. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01534

Di Fabio, A. (2015). Workplace Civility Scale: From dark side to positive side nelle organizzazioni [Workplace Civility Scale: From dark side to positive side in organizations]. Counseling. Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni, 8. http://rivistedigitali.erickson.it/counseling/archivio/vol-8-n-2/

Di Fabio, A., Giannini, M., Loscalzo, Y., Palazzeschi, L., Bucci, O., Guazzini, A. & Gori, A. (2016). The challenge of fostering healthy organizations: An empirical study on the role of Workplace Relational Civility in Acceptance of Change and Well-Being. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1748. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01748

Di Fabio, A., & Gori, A. (2016). Assessing Workplace Relational Civility (WRC) with a new multidimensional «mirror» measure. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00890

Di Fabio, A., & Kenny, M. (2018). Academic Relational Civility as a key resource for sustaining well-being. Sustainability, 10(6), 1914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10061914

Di Fabio, A., Kenny, M. E., & Claudius, M. (2017). Preventing distress and promoting psychological well-being in uncertain times through career management intervention. In M. Israelashvili & J. L. Romano (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of international prevention science (pp. 233-254). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Di Fabio, A., & Peiró, J. M. (2018). Human Capital Sustainability Leadership to promote sustainable development and healthy organisations: A new scale. Sustainability, 10(7), 2413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072413

Di Marco, D., Martínez-Corts, I., Arenas, A., & Gamero, N. (2018). Spanish Validation of the Shorter Version of the Workplace Incivility Scale: An employment status invariant measure. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 959. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00959

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71-75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D.-W., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143-156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

Eisenberger, R., Fasolo, P., & Davis-LaMastro, V. (1990). Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 51-59. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.75.1.51

Gori, A., & Topino, E. (2020). Predisposition to change is linked to job satisfaction: Assessing the mediation roles of workplace relation civility and insight. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 2141, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062141

Hage, S. M., Romano, J. L., Conyne, R. K., Kenny, M., Matthews, C., Schwartz, J. P., & Waldo, M. (2007). Best practice guidelines on prevention practice, research, training, and social advocacy for psychologists. The Counseling Psychologist, 35, 493-566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006291411

Lowe, G. (2010). The healthy organization. In G. Lowe (Ed.), Creating healthy organizations: How vibrant workplaces inspire employees to achieve sustainable success (pp. 16-41). University of Toronto Press.

Matthews, R. A., & Ritter, K. J. (2016). A concise, content valid, gender invariant measure of workplace incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21, 352-365. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000017

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill

Palazzeschi, L., Bucci, O., & Di Fabio, A. (2018) High Entrepreneurship, Leadership, and Professionalism (HELP): A new resource for workers in the 21st century. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1480. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01480

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Moorman, R. H., & Fetter, R. (1990). Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 1(2), 107-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(90)90009-7

Pozo Muñoz, C., Garzón Umerenkova, A., Nieto, B., & Charry, C. (2016). Psychometric properties and dimensionality of the «Flourishing Scale» in Spanish-speaking population. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 14, 175-192. https://doi.org/10.14204/ejrep.38.15044

Reed, L., Whitten, C., & Jeremiah, J. (2019). The importance of teaching civility as a workplace relationship building competency. Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning, 46, 168-174.

Seok, C.B., Mutang, J.A., Ching, P.L., & Ismail, R. (2022). Employees’ workplace relation civility in workplace: The role of positive relation management and accepted of change. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(7), 5458-4564.

Sleem, W.F., & Seada, A.M. (2017). Role of workplace civility climate and workgroup norms on incidence of incivility behaviour among staff nurses. International Journal of Nursing Didactics, 7(6), 34-43. https://doi.org/10.15520/ijnd.2017.vol7.iss6.230.34-43

Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., & Ullman, J. B. (2007). Using multivariate statistics. Pearson.

Tan, M.P.C., Kwan, S.S.M., Yahaya, A., Maakip, I., & Voo, P. (2020). The importance of organizational climate for psychosocial safety in the prevention of sexual harassment at work. Journal of Occupational Health, 62, e12192. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12192

World Health Organization (2007). Workers’ Health: Global Plan of Action. Sixtieth World Health Assembly. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA60/A60_R26-en.pdf

World Medical Association (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Journal of the American Medical Association, 310, 2191-2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053

Zayas-Ortiz, M., Rosario, E., Marquez, E., & Colón Gruñeiro, P. (2015). Relationship between organizational commitments and organizational citizenship behaviour in a sample of private banking employees. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 35(1/2), 91-106. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-02-2014-0010

Vol. 16, Issue 1, February 2023