Studi e ricerche / Studies and research

Time perspective and eudaimonic well-being in Italian emerging adults

Time perspective and eudaimonic well-being in Italian emerging adults

Manuela Zambianchi

Università di Bologna

Sommario

Hanno partecipato alla ricerca 204 adulti emergenti che hanno compilato la versione italiana della Swedish Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (S-ZTPI) ed il Questionario sul Benessere Psicologico (PWB). Le analisi multivariate hanno evidenziato differenze di genere sulla prospettiva temporale ed il PWB, mentre l’analisi correlazionale ha valutato la relazione tra questi due costrutti. Analisi di regressione gerarchica hanno esplorato il ruolo della prospettiva temporale sul PWB globale e su ogni sua sotto-componente, dopo aver controllato età e genere. Il passato positivo e il futuro positivo risultano correlati positivamente con il PWB globale, mentre il passato negativo, il presente fatalistico ed il futuro negativo risultano negativamente correlati con esso. Il PWB globale risulta legato a tutte le dimensioni della prospettiva temporale nella direzione ipotizzata.

Parole chiave

adulto emergente; prospettiva temporale; benessere eudaimonico; sviluppo positivo.

Abstract

Two hundred and four emerging adults participating in the research filled in the Italian version of the Swedish Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (S-ZTPI) and the Psychological Well-Being Questionnaire (PWB). Multivariate analyses provided evidences for gender differences on time perspective and psychological well-being; correlational analyses evaluated the relationship between these two constructs; a set of hierarchical regression models explored the role exerted by time perspective on PWB as global score and on its sub-components, after controlling for age and gender. Past positive and future positive resulted positively correlated with overall PWB, while past negative, present fatalistic and future negative resulted significantly, but negatively, correlated with it. Overall psychological eudaimonic well-being resulted in being predicted by all time perspective dimensions, in the expected, hypothesized directions.

Keywords

emerging adult; time perspective; eudaimonic well-being; positive development.

Introduction

The emerging adulthood represents a period of life, lasting from the late teens through the mid-to late twenties (Arnett, 2014). It represents a distinct phase of life from adolescence and also from the young adulthood, since it is characterized by a progressive autonomy for life choice, but hasn’t yet made the crucial role transitions such as marriage or stable cohabiting and acquisition of a stable job, that occur in the subsequent phase of young adulthood. This crucial life-phase of human development requests new tasks that they are called to face, with special attention for its psychosocial positive outcomes. Hawkins et al. (2009), proposed a complex and multidimensional model that identifies five competences that concur to accomplish this outcome, among which is life satisfaction, underlying the relevance of Positive Psychology as new area of investigation that can give a contribution to the understanding of human development at this stage of life.

Positive Psychology and successful development of the emerging adults. The role of psychological eudaimonic well-being

Positive Psychology represents a growing area of research that is focused on individual and social well-being, strengths and resources (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Peterson & Seligman, 2004), investigating several conceptualizations of well-being. The eudaimonic well-being derives from the ethical- philosophical speculations of the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE). Ryff (1989; Ryff & Singer, 2008) defined eudaimonic psychological well-being (PWB) as the resultant of six dimensions: Self-acceptance; Autonomy; Environmental Mastery; Personal Growth; Purpose in Life; Positive relations with others. Scholars approached the theme of eudaimonic well-being from other different theoretical conceptualizations: the search for a meaningful life (Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006) and the presence of a life of virtues (Vittersø, 2016). Since the emerging adulthood represents a life-stage where people lay the foundations of their life-course (eg. family, work career), the component of well-being as eudaimonia may be regarded with special importance.

Alandete, Martinez, Nohales and Lozano (2018) conducted a study aimed at evaluating the relation between meaning in life and psychological eudaimonic well-being in Spanish emerging adults. They found a positive correlation between these two constructs. Hill, Sumner and Burrow (2014) found that purpose in life represents a strong predictor of well-being in the emerging adults.

A longitudinal study (Hallam et al., 2013) tested the relevance of the involvement in eudaimonic behaviors (taking care of the environment, volunteering, fundraising for communities groups) during adolescence for the level of emotional competence in the subsequent stage of emerging adulthood. Results confirm the promotional role of these eudaimonic behaviors for the improvement of emotional competences. The emerging adulthood represents a life-stage during which people restructure and integrate their past, present and future time perspective, due to the reaching of a higher level of cognitive abstraction (Ricci Bitti, & Zambianchi, 2011). Time perspective, for this reason, may be of interest as relevant individual factor PWB.

Time perspective and positive functioning in the young generations

Frank (1939) considered time perspective as the influence of past experience and future plans on the processes of decision making and behavioral patterns in the present. Lewin, into his Field Theory, asserted the relevance of time perspective, regarded as «the totality of the individual’s views of his psychological future and his psychological past existing at a given time» (Lewin, 1943, p.75). Zimbardo and Boyd (1999) defined it as «the often nonconscious process through which individuals give order and coherence to their experiences» (p. 1271). It consists of five dimensions: Past positive; Past negative; Present hedonistic; Present fatalistic and Future. Carelli, Wiberg e Wiberg (2011) proposed an extended version of the original questionnaire developed by Zimbardo and Boyd (1999) that comprises two future time dimensions, namely the Future positive and Future negative.

Several studies have examined the role of time perspective in the psychological and social development of young people, highlighting its influence on several life domains such as risky and protective behaviors, strategies for managing daily and challenging situations, facets of well-being. Laghi, Baumgartner and Baiocco (2012) found that adolescents involved in risky behaviors such as binge drinking reported negative experiences in the past, possess a lower future orientation and a greater inclination to fatalism. Anagnostopulos and Griva (2011) explored the role of time perspective in Greek young adults on psychological functioning. They found that a negative view of the past and a fatalistic attitude toward life are positively associated with anxiety and depression, while a future time perspective orientation is related with proactive coping. Taber and Blankemeyer (2015) examined the relationships between time perspective and vocational identity statuses in a sample of 165 emerging adults. Results showed that a diffuse vocational identity is associated with a negative view of the past and inversely related to the capacity to look forward the future, while the achieved vocational identity is positively associated with the capacity to enjoy the present and making connections between current behaviors and future outcome. Steger, Kashdan, Sullivan and Lorentz (2008) found positive relationships between search of meaning in life and a positive view of the past, a planning future and the ability to enjoy of present relationships, while negative, traumatic past experiences compromise the existential tension towards the search for meaning in life. Shterjovska and Achkovska-Leshkovska (2018) investigated the role of time perspective for meaning in life and subjective well-being in Macedonian undergraduated students. They found that subjective well-being is associated with the presence of meaning in life, an orientation toward present pleasure, a positive view of the past, lack of negative past experiences and positive future orientation. A new emergent time-based construct is the Balanced Time Perspective (BTP) (Boniwell & Zimbardo, 2004) that corresponds to a deep concentration on a positively perceived past, moderate concentration on the future, moderate hedonistic concentration on the present, poor fatalistic concentration on the present, and poor concentration on a negatively perceived past (Sobol-Kwapinska & Jankowski, 2016). Boniwell, Osin, Linley and Ivanchenko (2010) highlighted that individuals possessing a time profile similar to BTP was characterized by a stronger sense of meaning in life, greater life satisfaction, higher subjectively perceived well-being, greater optimism and a stronger perceived self-efficacy.

The role of time perspective for PWB constitutes nowadays a quite understudied area of inquiry in the period of emerging adulthood; for this reason this study has taken into consideration the relevance of time perspective for the eudaimonic well-being (PWB), formulating the following objectives:

– to evaluate the level of eudaimonic well-being and the characteristic of the time perspective of the emerging adults;

– to evaluate the presence of differences for gender on time perspective and eudaimonic well-being;

– to evaluate the correlations between time perspective dimensions, overall eudaimonic well-being and its sub-components. It was hypothesized the presence of positive correlations between past positive, present hedonistic, future positive and the overall eudaimonic well-being. On the contrary, negative correlations between past negative, present fatalistic, future negative and overall eudaimonic well-being as well as its sub-components are expected;

– to evaluate the predictive power of time perspective dimensions for overall eudaimonic well-being and its sub-components, after controlling for age and gender as structural variables.

Method

Participants

Two hundred and four emerging adults, (mean age = 21,61; SD = 2,99; range = 19-30; women = 85 [49%]; men = 108 [56%]) participated in the study. They were recruited at the University of Bologna and in companies of North Italy. They filled in the following self-report measures.

Measures

Swedish Zimbardo Time Perspective (Carelli, Wiberg, & Wiberg, 2011). This questionnaire contains 64 items and is designated to evaluate six fundamental time dimensions: Past positive (a positive evaluation of the past, perceived as bearing of values and experiences, e.g «Familiar childhood sights, sounds, smells often bring back a flood of wonderful memories»), α = .75 (0.66); Past negative (which reflects a negative and traumatic view of the past, with not yet elaborated events, e.g. «The past has too many unpleasant memories that I prefer not to think about»), α = .77 (0.81); Present hedonistic (an orientation toward present enjoyment and pleasure, without sacrifices today for rewards tomorrow, e.g. «I believe that getting together with one’s friends to party is one of life’s important pleasure»), α = .78 (0.76); Present fatalistic (a belief that the future is predestined and uninfluenced by human actions, e.g. «Fate determines much in my life»), α = .61(0.74); Future positive (efforts to plan for achieving future objectives, e.g. «When I want to achieve something, I set goals and consider specific means for reaching those goals»), α = .77(0.65); Future negative (a threatening and anxious perception of the future, e.g. «The future contains too many boring decisions that I do not want to think about»), α = .55 (0.68). The score was computed on a 5 point Likert scale (1 = «Very untrue»; 5 = «Very true»).

Psychological Well-being Questionnaire (PWB) (Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Ruini et al., 2003). This self-report instrument contains 48 items that evaluated six dimensions: Autonomy (the capacity to evaluate oneself by personal standards and acquire a strong sense of independence, e.g. «I have confidence in my opinions, even if they are contrary to the general consensus»), α = .57 (α = .88); Environmental Mastery (the individual’s ability to choose or create environments suitable to her/his qualities, e.g. «In general, I feel I am in charge of my situation in which I live»), α = .65 (α = .81); Positive relations with others (the ability to construct warm, trusting interpersonal relationships, e.g. «People would describe me as a giving person, willing to share my time with others»), α = .80 (α = .83); Purpose in Life (have a clear comprehension of life purpose, a sense of directedness and intentionality, e.g. «Some people wonder aimlessy through life, but I am not one of them»), α = .49 (α = .82); Personal Growth (the individual’s perception of being a growing and expanding person, e.g. «I think it is important to have new experiences that challenge how you think about yourself and the world»), α = .71 (α = .81); Self-Acceptance (the possession of a positive attitude toward the self and the acceptance of good and bad qualities, e.g. «I like most aspects of my personality»), α = .82 (α = .85). The α coefficient for the overall psychological well-being score is 0.82. The score may range from 1 to 6 (1 = «It’s not my case»; 6 = «It’s exactly so»).

Procedures

For the sub-sample of undergraduate (N =173; 85%), the recruitment occurred during their lessons, after having been authorized by their professors to present the research project, while the sub-sample of working emerging adults (N= 31; 15%) were recruited in the workplace through contacting the management. For both groups there were no problems understanding the questionnaires. After being briefly informed of the objectives of the study and the anonymity of the questionnaires they gave their consent and filled in the questionnaires.

Data analysis

The analyses were run in four steps. Firstly, mean, standard deviations, skewness and kurtosis of all variables were calculated. In the second step, MANOVA Models were run for evaluating groups differences (gender) for time perspective and psychological eudaimonic well-being. Subsequent ANOVAs evaluated the differences in a more detailed way. In the third step, a Pearson correlational matrix was calculated. Finally, seven hierarchical regression models evaluated the predictive value of time perspective dimensions on overall psychological eudaimonic well-being and on its specific sub-components.

Results

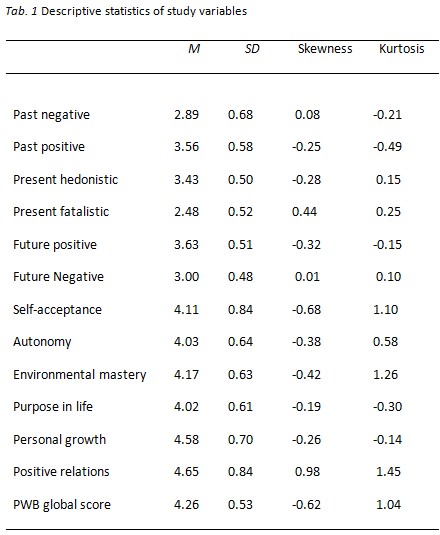

Descriptive statistics of study variables

The emerging adults have the highest scores, for overall PWB, on the dimensions of Positive relations with others and on Personal growth; as regards time perspective, the highest scores are on Past positive, on Future positive and on Present hedonistic (see Table 1).

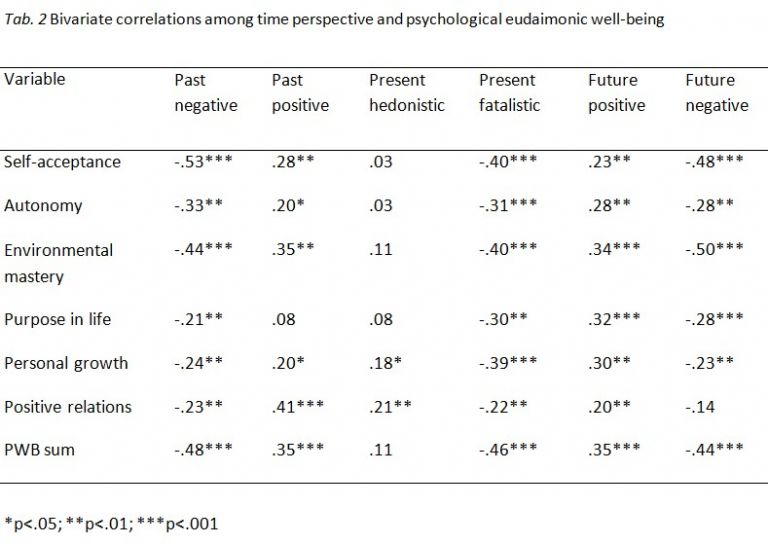

Correlations between time perspective and psychological eudaimonic well-being (PWB)

The overall PWB and its sub-components are significantly correlated with all the dimensions of time perspective, with the exception of Present hedonistic, which is correlated only with the dimensions Personal growth and Positive relations with others (see Table 2).

Gender differences for time perspective and eudaimonic well-being

A first Manova model with gender as grouping variable and the six time perspective dimensions as dependent variables resulted statistically significant.

A first Manova model that placed gender as a grouping variable and the six dimensions of time perspective as independent variables resulted as statistically significant (Wilk’s Lambda = .90; F [6,159] = 2,80; p<.01), with women being more focused on Present fatalistic than men (Men: M = 2.39; Women: M = 2.56; F = 4,14; p < .01, η = .02) and with a more pronounced Past negative than men (Men: M = 2.81; Women: M = 3,04; F = 4,85; p < .05). Women show a higher Future positive than men (Men: M = 3.54; Women: M =3.75; F =7,13; p < .01; η = .04).

A second Manova model with gender as a grouping variable, the six dimensions of eudaimonic well-being and the overall PWB as dependent variables was statistically significant (Wilk’s Lambda = .91; F [6,168] = 2.44; p <.05). Men reported a slightly higher level of Autonomy (Men: M = 4.11; Women: M = 3.93; F = 2.93; p < .08; η = .01) and a lower level of Positive relations with others than women (Men: M = 4.55; Women: M = 4.86; F = 7.18; p < .01; η = .03).

Age differences for PWB and S-ZTPI

A set of linear regression models were performed, with age as a continuous independent variable and overall PWB, its sub-dimensions, and time perspective as dependent variables. For PWB, age resulted as a significant contributor only for Purpose in life, increasing in value as age increases (β = .25; standard error of Beta = .06; p < .001; adj. R2= .05). For time perspective, age was found to be a significant contributor for Present hedonistic, decreasing in value as age increases (β = -.14, standard error of Beta =-.011, p < .05, adj. R2 = .01).

The contributors of psychological eudaimonic well-being

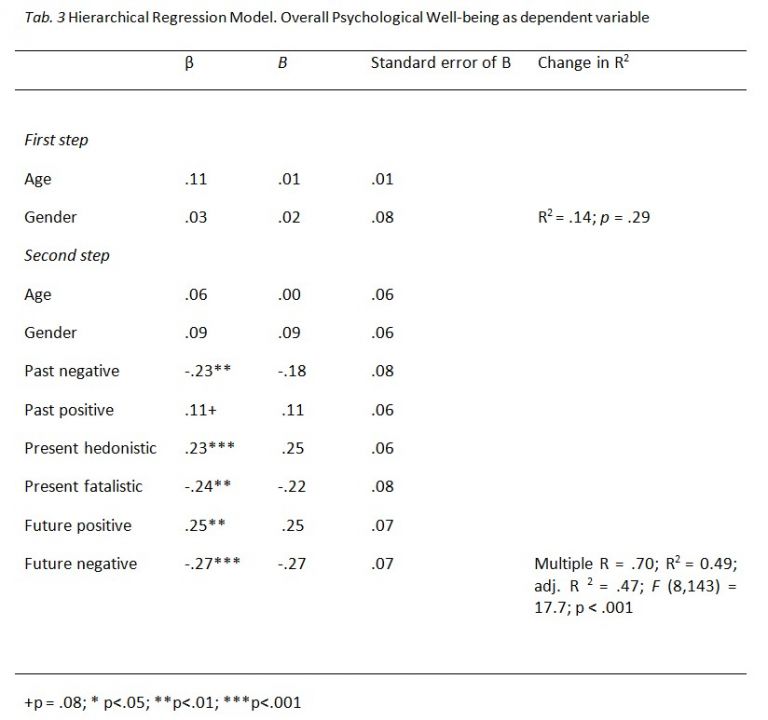

A set of seven hierarchical regression models with gender and age as independent structural variables and the six dimensions of time perspective as independent variables were performed.

Overall PWB. Neither gender nor age, included in the first regression step, resulted as significant contributors. In the second step the six dimensions of time perspective were added, all of which proved to be significant contributors. Past negative, Present fatalistic and Future negative make a negative contribution to the explained variance, while Past positive, Present hedonistic and Future positive give a positive contribution to it. Time perspective contributes to 47% of the explained variance (see Table 3).

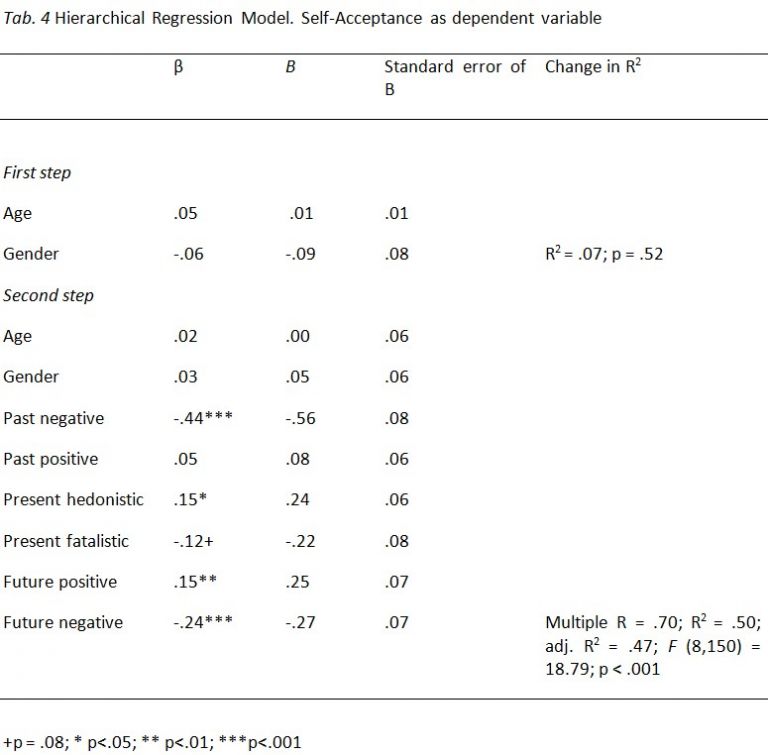

Self-acceptance. In the first step, this dimension was not related either to gender or age. By entering time perspective in the second step, this component of PWB appears to be related to Past negative, the most robust predictor, Present hedonistic, Future positive and Future negative. Multiple R = .70; R2 = .50; adj. R2 = .47; F (8,150) = 18.79; p < .001 (see Table 4).

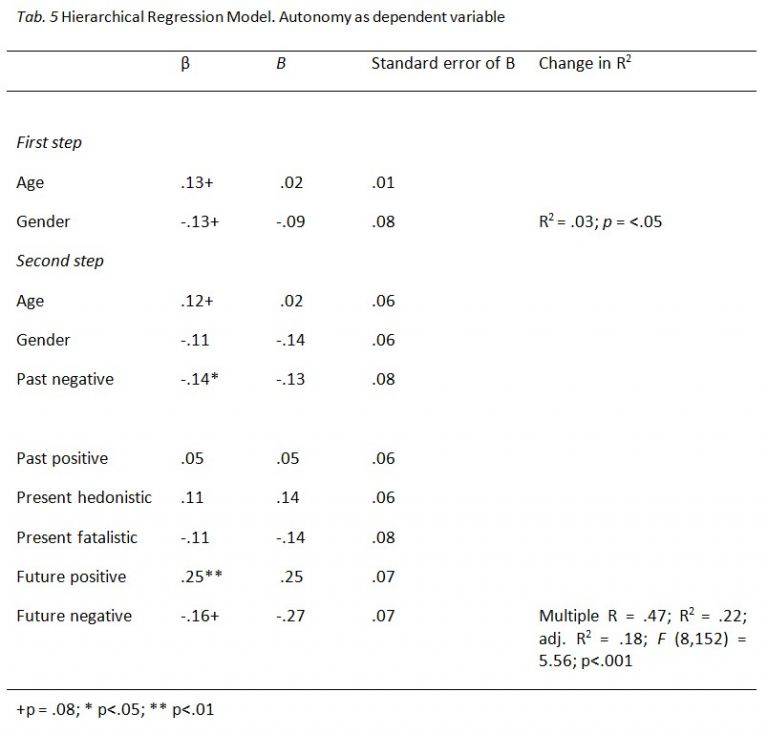

Autonomy. In the first step gender and age approach statistical significance. In the second step, after having inserted time perspective, gender becomes not significant, while age maintains its value approaching the statistical significance. For the dimensions of time perspective, only Future positive was significant, while Future negative tended to significance. Multiple R = .47; R2 = .22; adj. R2 = .18; F (8,152) = 5.56; p < .01 (see Table 5).

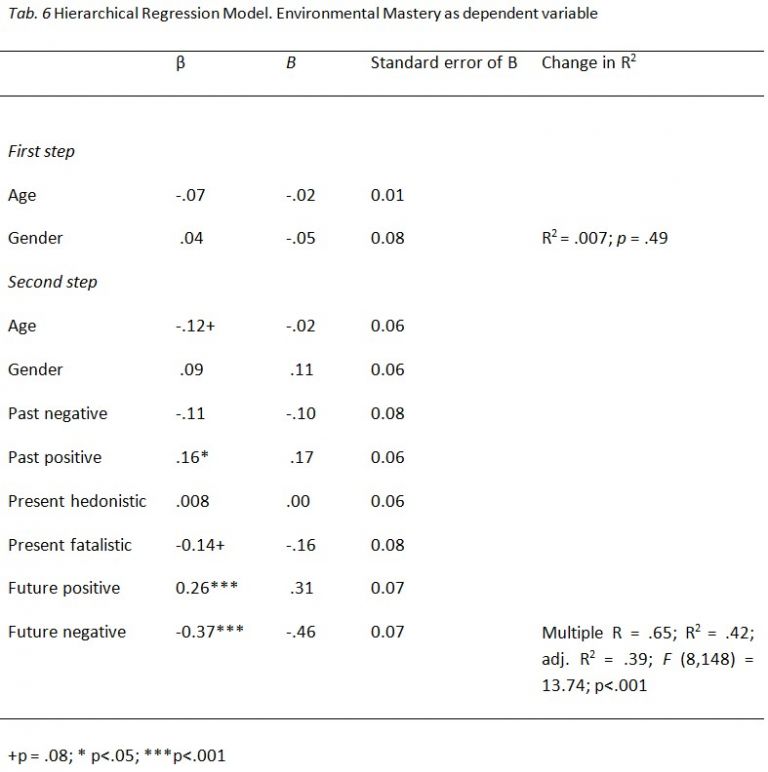

EnvironmentalMastery. In the first step, neither age nor gender were significant. After entering time perspective, age tended to significance. Past positive and Future positive resulted as significant positive contributors; Present fatalistic and Future negative instead as significant negative contributors. Multiple R = .65; R2 = .42; adj. R2 = .39; F(8,148) = 13.74; p < .001 (see Table 6).

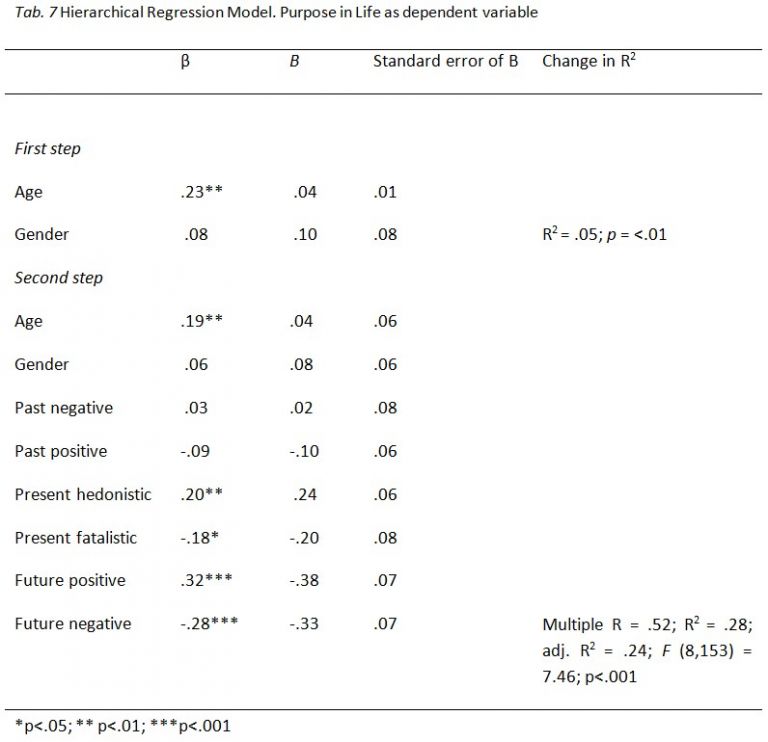

Purpose in life. In the first step of the regression, age was a significant and positive contributor, while gender was not significant. After having inserted time perspective, age maintained its significance. For time perspective, Present hedonistic and Future negative emerged as positive contributors, Present fatalistic and Future negative as negative contributors. Multiple R = .52; R2 = .28; adj. R2 = .24; F(8,153) = 7.46; p < .001 (see Table 7).

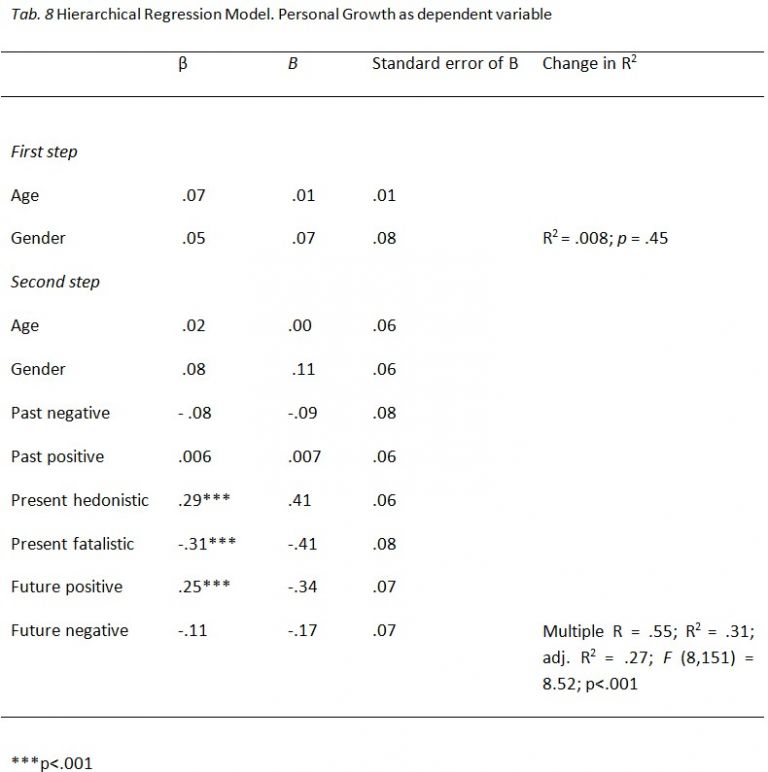

Personalgrowth. In the first step, neither age nor gender were significant. After entering time perspective, Present hedonistic turned out to be a positive contributor along with Future positive. On the contrary, Present fatalistic resulted as a negative contributor. Multiple R = .55; R2 = .31; adj. R2 = 0.27; F(8,151) = 8.52; p < .001 (see Table 8).

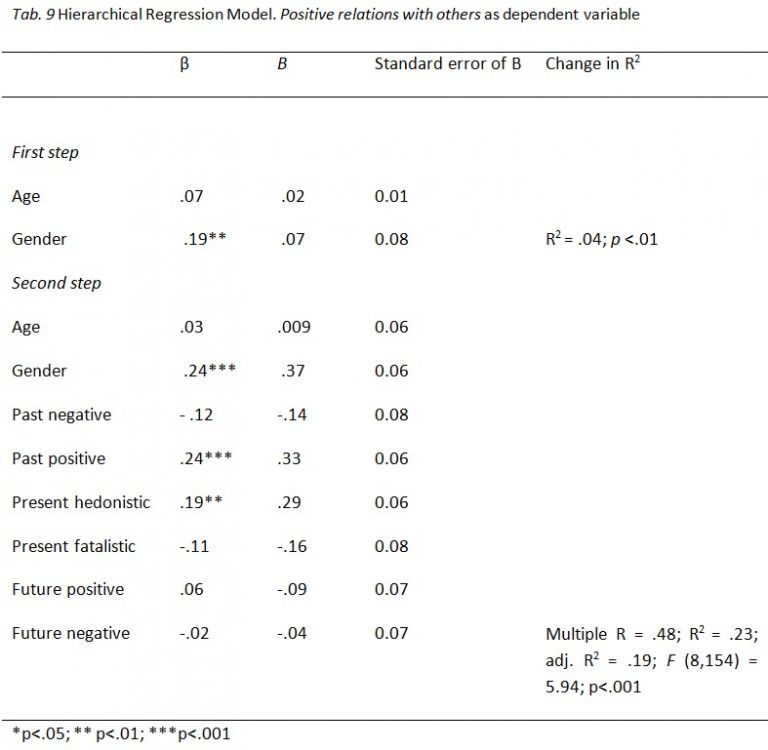

Positiverelationswithothers. In the first step, gender was found to be a positive significant contributor. After including time perspective, gender retained its significance, reinforcing its value. Past positive turned out to be the most important time contributor; Present hedonistic also makes a positive and significant contribution. Multiple R = .48; R2 = .23; adj. R2 = .19; F(8,154) = 5.94; p < .001 (see Table 9).

Discussion

The study has investigated the role of time perspective for PWB in the emerging adulthood, taking into consideration also gender and age as structural variables. Results confirm the relevance of this time construct for PWB. The emerging adults possess a positive high tendency toward personal growth and positive relationships. An unexpected result is the lower level of Purpose in life, that is in contrast with other previous studies (Ryff & Singer, 2008; Steca, Ryff, D’Alessandro, & Delle Fratte, 2002). This data, especially if compared to the Italian study by Steca, Ryff, D’Alessandro and Delle Fratte (2002) could be an indication of a growing difficulty of the emerging adults in imagining and projecting themselves in the future, and can be related both to the delay of entering into an adult perspective and in achieving adult roles, as stated Arnett (2014), and to the effect of the profound transformations of our postmodern society, such as a progressive reduction of the perceived future time extension (Leccardi, 2005) and a growing difficulty of linking the actions undertaken in the present to their future outcomes. The difficulty in finding stable work, a problematic situation that has emerged in Italy during the last years (ISTAT, 2018), increases, of course, the envisioning of a negative future and undermines the personal project of the emerging adults.

For time perspective, women appear to be more Present fatalistic oriented than men, possessing, at the same time, a higher level of Future positive than their men peers. Women perceive moreover their past as more problematic than men. The first result can be perhaps traced back to the tendency of women to be less agentic, or to perceive for themselves less Self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997). On the contrary, they envision a more positive future than men, as another study (Mello & Worrell, 2006) conducted on adolescents has highlighted. Perhaps, a growing equality of opportunities for both sexes, opens new windows for self-realization and increasing hope in the future. Gender influences also two sub-components of PWB. Women appear to be more able to create and maintain good relationships, in accordance to the stereotypical view of them as «weavers of relationships» (Perez, 2012; Steca, Ryff, D’Alessandro, & Delle Fratte, 2002).

The relevant role exerted by time perspective on PWB is confirmed by the results of the regression models. The overall PWB is predicted by all the time perspective dimensions, and in the expected direction: negative past experiences, a fatalistic perception of the present, the envisioning of a threatening future, together they concur to undermine the human tendency toward actualization of own talents and potentials. On the contrary, positive time dimensions such as Past positive, the envisioning of a positive future favor the experience of high PWB. Sub-components of PWB are related to specific time perspective dimensions, as hypothesized. The meaningfulness of the negative, traumatic past experiences is reflected in its robust, negative relation with Self-acceptance. Past positive do not show any significant relevance for this dimension, confirming the long-lasting and more strong effects of the negative early experiences for the inner self (Sailer et al., 2014). The perception of the future contributes also to an high level of Self-acceptance; perhaps, the capacity to integrate into a coherent self the positive and negative psychological qualities could denote the reach of a stable, mature sense of identity, that enable the emerging adults to make plans for their future, as the study of Tabert and Blankemeyer (2015) seems to indicate. The ability of enjoying the present time with friends also contributes to a more positive view of the self, confirming that «being in the present» not necessarily constitutes a risk factor for positive development, as other research has highlighted (e.g. Taber & Blankemeyer, 2015; Rönnlund, Åström, Adolfsson, & Carelli, 2018).

Purpose in life is related to the ability of enjoying the present and by the ability of planning for a constructive future, while the mental anticipation of a future with negative outcomes and the perception to be out of control on the present undermine the construction of personal life projects.

The dimension of Personal growth is also related to the present and future time dimensions. The central role played by Present hedonistic suggests that high quality personal and cultural experiences are at the basis of the self-perception of growing as a person, at least in this stage of life. These positive experiences lay the foundations of planning for the future, according to the identity theories (Crocetti, Erentaitè, & Zukauskiene, 2014), that suggests the knowledge about the self, about personal resources and vocations as the necessary premise for accomplishing future objectives (identity achievement status). On the contrary, a fatalistic view of the present compromises the inner growth of the young people, together with the envisioning of a negative or threatening future, that can reduce their intrinsic motivation. The presence of satisfying relationships is related to having experienced at an early age of life positive family and social environments (Past positive), that provided children of secure models of attachment (Bowlby, 1988) and constructive models of interpersonal communication. These models can be «transferred» to actual social relationships (Saribay & Andersen, 2007). The Environmental mastery is positively predicted by positive past experiences: these early experiences could have provided the acquisition of constructive relational-communicative skills and create a representation of the others as trustful, helping in the present the construction of solid relationships and for identifying suitable environments. Instead the presence of a fatalistic view of the world and of a negative future compromises the ability of the emerging adult to exert an agentic, proactive role on the surrounding environment, perhaps due to the lack of hope.

Implications for interventions

The centrality of psychological time for human functioning is nowadays well established (Zimbardo & Boyd, 2008), opening new windows of opportunities for interventions aimed at improving well-being and psychological functioning through time-based interventions. The time perspective-based temporal interventions (e.g. coaching, counseling, psychotherapy) offer a relevant opportunity of personalized interventions that are based on the time perspective construct (Sword, Sword & Zimbardo, 2012; Boniwell & Osin, 2015). Having established that overall PWB is significantly linked to the totality of time perspective dimensions, it is important to identify effective temporal interventions for reducing the prominence of negative ones and, on the contrary, improving the constructive time frames. For example, having past negative a strong effect on overall PWB, interventions aimed at improving skills and techniques such as the «expressive writing» (Pennebaker, 2004) can help the emerging adult to give meaning, coherence to his/her negative early experiences reducing, at the same time, their over-presence in mind. The ability to identify life priority and objectives, in accordance with personal interests, motivation and talents can help the emerging adults in reaching a broader, deeper and positive view of the future. At the same time, temporal based-interventions can enhance, or strengthen, the PWB sub-components. Given, for example, the relevance of Future negative, as other research has demonstrated (Rönnlund, Astrom, Adolfsson & Carelli, 2018), it will be of priority to identify strategies for reducing its influence on overall PWB and several its sub-dimensions, such as Environmental mastery and Purpose in life. Interventions based, e.g. on the improvement and utilization of proactive coping skills (Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997) can increase the perception of mastery and self-efficacy toward the future of the emerging adults. These coping skills, indeed, pertain to the ability of envisioning and hypothesizing future scenarios, of identifying precocious signals of negative future criticalities, and act in the present in order to avoid negative outcomes. These skills are of growing relevance in our post-modern society, characterized by the increasing in future unpredictability, a societal characteristic that could be regarded as a risk factor for life projects and planning in the youngest generations. The highlighted relationship between time perspective and eudaimonic well-being can have important implications for counseling, through interventions aimed at developing skills and resources to improve a favorable time organization for positive evolution of the emerging adults.

Through indeed the knowledge of the temporal dimensions involved in specific components of eudaimonic well-being, it is possible for the counselor to plan forms of active intervention that help the individual to acquire more resources to reduce the meaningfulness of critical times and above all to enhance positive times, such as future positive and present hedonistic for Personal growth and Purpose in life, central dimensions in the stage of emerging adulthood for career and family planning.

A growing area of interventions concerns the construct of Balanced Time Perspective, that corresponds to an optimal blend of Past positive, Present hedonistic and Future positive (Boniwell & Zimbardo, 2004). Several research has demonstrated the relevance of possessing a balanced time perspective for positive functioning, well-being and lower level of perceived stress (Rönnlund, Åström, Adolfsson, & Carelli, 2018).The technique(s) of mindfulness, that is defined as the ability to pay attention to the experiences that are occurring in the present moment together with a non-judgmental attitude towards them (Kabat-Zinn, 2005), appears to be of growing relevance for enhancing the well-being of individuals and favor the reaching of a holistic, inner integration of past, present and future (Rönnlund, Åström, Adolfsson, & Carelli, 2018; Rönnlund et al., 2019). Nowadays there is a scarcity of research that takes into consideration the linkage between eudaimonic well-being and the mindfulness techniques of meditation, but results (Kay, Hafenbrack, & Skarlicki, 2017) are positive and encourage the development of future studies on this topic.

Limits of the study

The study presents several limits. The first is about the not optimal psychometrics properties of several dimensions, that request caution for the conclusions to be drawn. Another limit is the cross-sectional nature of the study, that do not allow to delineate a causal model of influence of time perspective: only longitudinal studies, in a future time, can disentangle this question. Despite these important limits, the study highlights the importance of time perspective for a broader comprehension of the individual factors that are implicated in the perception on well-being in an eudaimonic perspective and in a crucial phase of life such as the emergence of the psychological adult structure.

Acknowledgement

The Author sincerely thanks Confcommercio Ascom Lugo, Faenza and Ravenna for their collaboration in recruiting the employed emerging adults.

References

Alandete, J. G., Martinez, E. R., Nohales, P. S., & Lozano, B. S. (2018). Meaning in Life and Psychological Well-Being in Spanish Emerging Adults. Acta Colombiana de Psicologia, 1, 196-205. doi: http://www.dx.doi.org/10.14718/ ACP.2018.21.1.9.

Anagnostopulos, F., & Griva, F. (2011). Exploring time perspective in Greek young adults: validation of the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory and relationships with mental health indicators. Social Indicators Research, 1, 41-59. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9792-y.

Arnett, J. J. (2014). Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Aspinwall, L. G., & Taylor S. E. (1997). A stitch in time: self-regulation and proactive coping. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 417-436.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Boniwell, I. (2005). Beyond time management: How the latest research on time perspective and perceived time use can assist clients with time-related concerns. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 3(2), 61-74.

Boniwell., I., Osin, E., Linley, P. A., & Ivanchenko, G. V. (2010). A question of Balance: Time perspective and well-being in British and Russian samples. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 24-40.

Boniwell, I., & Osin, E. (2015). Time Perspective Coaching. In M. Stolarski et al. (Eds.), Time Perspective Theory; Review, Research and Application: Essays in Honor of Philip G. Zimbardo (pp. 451-469). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-07368-2_29.

Boniwell, I., & Zimbardo, P. (2004). Balancing Time Perspective in Pursuit of Optimal Functioning. In P. A. Linley, & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive Psychology in Practice (pp. 165-179). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books.

Carelli, G., Wiberg, B., & Wiberg, M. (2011). Development and construct validation of the Swedish Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 4, 220-227. doi: org710.1027/1015-5759/a000076.

Crocetti, E., Erentaitè, R. & Zukauskiene, R. (2014). Identity styles, positive youth development, and civic engagement in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 11, 1818-1828. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0100-4.

Frank, K. (1939). Time Perspective. Journal of Social Phylosophy, 4, 293-312.

Hallam, W. T., Olsson, C.A., O’Connor, M., Hawkins, M., Tombourou, J. W., Bowes, G., McGee, R., & Sanson, A. (2013). Association Between Adolescent Eudaimonic Behaviours and Emotional Competence in Young Adulthood. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 1165-1177.

Hawkins, M. T., Lechter, P., Sanson, A., Smart, D. & Tombourou, J. W. (2009). Positive development in emerging adulthood. Australian Journal of Psychology, 2, 89-99. doi: 10.1080/00049530802001346.

Hill, P. L., Sumner, R., & Burrow, A. L. (2014). Understanding the pathways to purpose: Examining personality and well-being correlates across adulthood. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(3), 227-234.

ISTAT (2018). Annual Report 2018: The State of the Nation. Retrieved from https://www.istat.it/it/files/2018/06/AnnualReport2018.pdf

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York, NY: Hyperion Books.

Kay, A. A., Hafenbrack, A., & Skarlicki, D. (2017). Enhancing Eudaimonic Well-Being with Mindfulness: The moderating effect of authenticity. Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings, 1, 14366. doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2017.14366abstract.

Laghi, F., Baumgartner, E., & Baiocco, R. (2012). Time perspective and psychosocial positive functioning among Italian adolescents who binge eat and drink. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 1277-1284. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence2012.04.014.

Leccardi, C. (2005). Facing uncertainty. Temporality and biographies in the new centuries. Young. 13 (2), 123-146. doi: 10.1177/1103308805051317.

Lewin, K. (1943). Defining time the field at a given time. Psychological Review, 50, 292-310.

Mello, Z. R., & Worrell, F. C. (2006). The relationships of time perspective to Age, Gender and Academic Achievement among Academically Talented Adolescents. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 29 (3), 271-289.

Pennebaker, J. W. (2004). Writing to heal. A guided journal for recovering to trauma and emotional upheaval. New Harbinger Press: Oakland, CA.

Perez, J. A. (2012). Gender differences in Psychological Well-being among Filippino College Student Sample. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2 (13), 84-93.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues. A handbook and classification. New York: Oxford University Press and Washington DC: APA.

Ricci Bitti, P.E., & Zambianchi, M. (2011).Organizzare la vita quotidiana e progettare il futuro. (organize daily life and planning the future). In A. Palmonari (Ed.), Manuale di Psicologia dell’adolescenza (Handbook of Psychology of Adolescence) (pp. 165-183). Bologna: il Mulino.

Rönnlund, M., Åström, E., Adolfsson, R., & Carelli, M. G. (2018). Perceived stress in adults aged 65 to 90: relations to facets of time perspective and COMT Val158Met polymorphism. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 378. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00378.

Rönnlund, M., Koudriavstseva, A., Germundsjo, L., Eriksson, T., Astrom, E., & Carelli, M. G. (2019). Mindfulness promotes a more balanced time perspective. Correlational and intervention-based evidence. Mindfulness, 10(8), 1579-1591. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01113-x.

Ruini, C., Ottolini, F., Rafanelli, C., Ryff, C. D. & Fava, G. A. (2003). La validazione italiana delle Psychological Wellbeing Scales (PWB). Rivista di Psichiatria, 3, 117-129.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything or is it? Explorations on the meaning of Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 13-39.

Ryff, C. D. & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personal and Social Psychology, 69, 719-727.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: a eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 13-39.

Sailer, U., Rosenberg, P., Nima, A. A., Gamble, A., Gärling, T., Archer, T., & Garcia, D. (2014). A happier and less sinister past, a more hedonistic and less fatalistic present and a more structured future: time perspective and well-being. PeerJ, 2, e303. doi: https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.303.

Saribay, S. A., & Andersen, S. M. (2007). Are past relationships at the heart of attachment dynamics? What love has to do with it. Psychological Inquiry,18 (3) 183-191.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5-14.

Shterjovska, M., & Achkovska-Leshkovska, E. (2018). Time Perspective, meaning in life and subjective well-being in Macedonian undergraduate students. In V. Ortuno & P. Cordeiro (Eds.), International Studies in Time Perspective (pp. 131-140). Coimbra: Coimbra University Press. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-0775-7.

Sobol-Kwapinska, M., & Jankowski, T. (2016). Positive time: Balanced time perspective and positive orientation. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(4), 1511-1528.

Steca, P., Ryff, C. D., D’Alessandro, S., & Delle Fratte, A. (2002). Psychological Well-being: gender and age differences in the Italian context. Psicologia della Salute, 2, 121-143.

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the Presence and Search for Meaning in Life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, (1), 80-93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80.

Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B., Sullivan, B. A., & Lorentz, D. (2008). Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of Personality, 76, 199-228.

Sword, R. M., Sword, K. M. R. & Zimbardo, P. G. (2012). The Time Cure: Overcoming PTSD with the New Psychology of Time Perspective Therapy. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Taber, B. J. & Blankemeyer, M. S. (2015). Time Perspective and Vocational Identity Statuses of Emerging Adults. Time Career Development, 63, 113-125. doi: 10.1002/cdq.12008.

Vittersø, J. (2016). The most important idea in the world: An introduction. In J. Vittersø (ed.). Handbook of eudaimonic well-being (p. 1-24). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Putting Time in Perspective: a valid, reliable individual- differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 6, 1271-1288. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1271.

Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (2008). The Time Paradox. The new Psychology of Time that can change your life. New York: Free Press.

Autore per la corrispondenza

M. Zambianchi. Tel. +3390547-338520; Fax +390547338503 Indirizzo e-mail: E-Mail: manuela.zambianchi@unibo.it Università di Bologna, Viale Europa 109, 47521 Cesena

Note

1 A

© 2017 Edizioni Centro Studi Erickson S.p.A. ISSN 2421-2202. Counseling. Tutti i diritti riservati. Vietata la riproduzione con qualsiasi mezzo effettuata, se non previa autorizzazione dell'Editore.