Introduction

Perfectionism can be defined as a personal characteristic characterized by struggling for excellence and holding extremely high standards for performance alongside excessively critical evaluations of one’s own actions (Frost, Marten, Lahart, & Rosenblate, 1990; Hewitt & Flett, 1991; Smith, Saklofske, Stoeber, & Sherry, 2016). Evidence suggests two higher-order factors underlie and account for the majority of common variance among several lower-order perfectionism dimensions: personal standards perfectionism, and evaluative concerns perfectionism (Dunkley, Blankstein, Halsall, Williams, & Winkworth, 2000; Dunkley, Blankstein, Masheb, & Grilo, 2006; Sherry, Gautreau, Mushquash, Sherry, & Allen, 2014).

Personal standards perfectionism characterizes a propensity to require perfection of oneself (Hewitt & Flett, 1991) and the tendency to establish unrealistically high personal standards (Frost et al., 1990). Evaluative concerns perfectionism is comprised of an array of characteristics including the propensity to perceive the demand of perfection by others (Hewitt & Flett, 1991), experience excessively negative reactions in relation to failures as for the dimension concerns over mistakes by Frost et al. (1990) and worries about performance skills as underlined by the dimension of doubt about actions (Frost et al., 1990). Personal standards perfectionism has two faces (Smith et al., 2016): a negative one that considers perfectionism linked to negative aspects such as neuroticism, ruminative brooding and depression (Hewitt & Flett, 2004) and a positive one that sees perfectionism related to positive characteristics in terms of conscientiousness and task-oriented coping (Blankstein & Dunkley, 2002; Rice, Ashby, & Slaney, 2007). Instead evaluative concerns perfectionism has only a dark side correlating with negative affect and many indicators of psychological maladjustment (Stoeber & Otto, 2006).

Perfectionism is a construct that deserves to be further studied and for this reason starting from an in-depth analysis of the literature Smith et al. (2016) developed a multidimensional perfectionism scale that permit a very accurate and comprehensive evaluation of the construct. The Big-Three Perfectionism Scale (BTPS, Smith et al., 2016) is composed of 45 items and detects three global perfectionism factors (Rigid perfectionism, Self-critical perfectionism, and Narcissistic perfectionism) with ten core perfectionism facets (two facets for Rigid perfectionism: Self-oriented perfectionism and Self-worth contingencies; four facets for Self-critical perfectionism: Concern over mistakes, Doubts about actions, Self-criticism, and Socially-prescribed perfectionism; four facets for Narcissistic Perfectionism: Other-oriented perfectionism, Hypercriticism, Entitlement, and Grandiosity). Rigid perfectionism regards the rigid persistence that one’s own performance must be perfect and impeccable in terms of self-oriented perfectionism that is strong need to be perfect and self-worth contingencies as feeling to be worthwhile only if one is perfect. Self-critical perfectionism was developed according to the model by Dunkley, Zuroff, and Blankstein (2003) that includes four facets: Concern over mistakes is the propensity to have excessively negative reactions to perceived failure (Frost et al., 1990); Doubts about actions concerns worries about performance (Frost et al., 1990); Self-criticism regards the propensity to involve in severe self-criticism when performance is not perfect (Dunkley et al., 2003); Socially prescribed perfectionism is relative to a propensity to perceive others as requiring perfection (Hewitt & Flett, 1991).

The third global factor Narcissistic perfectionism was developed based on Nealis, Sherry, Sherry, Stewart, and Macneil (2015) model and comprises four facets: Other-oriented perfectionism is the propensity to have excessive expectation for others (Hewitt & Flett, 1991). Hypercriticism includes cruel devaluation of others and their inadequacies (Nealis et al., 2015). Entitlement regards the belief that individuals think to deserve a special treatment (Nealis et al., 2015). Grandiosity concerns the belief of individuals to consider themselves as perfect or superior to others (Flett, Sherry, Hewitt, & Nepon, 2014; Nealis, Sherry, Lee-Baggley, Stewart, & Macneil, 2016; Stoeber, Sherry, & Nealis, 2015). The BTPS is the first and only scale that comprises a measure of narcissistic perfectionism. The Big Three Perfectionism Scale (BTPS) resulted as a valid and reliable measure in two different university samples and one community sample confirming the structure with three global factors and ten facets.

The Big Three Perfectionism Scale (BTPS) represents the more updated and comprehensive measure of perfectionism and for this reason it could be important to have this instrument available to study the construct also in the Italian context. Thus, the aim of the present study is to offer a first contribution to the validation of the Italian short form of the Big-Three Perfectionism Scale (BTPS-SF).

Method

Participants

Two hundred and eighty-eight Italian university students of the University of Florence were involved in the study (84 males, 29.17%; 204 females, 70.83%; mean age = 23.33; DS = 3.12).

Measures

The Italian short form of the Big-Three Perfectionism Scale (BTPS-SF). The BTPS-SF (by Di Fabio, Saklofske, and Smith) is composed of 18 items (six items for each of the three dimensions) with response format on Likert scale from 1 = Strongly agree to 5 = Strongly disagree. The scale permits to detect the three global perfectionism factors: Rigid perfectionism, Self-critical perfectionism, and Narcissistic perfectionism. Rigid perfectionism includes items of two facets of the original version: Self-oriented perfectionism (example of item: «I have a strong need to be perfect» and Self-worth contingencies (example of item: «I could never respect myself if I stopped trying to achieve perfection»). Self-critical perfectionism includes items of four facets of the original version: Concern over mistakes (example of item: «The idea of making mistakes frightens me»), Doubts about actions (example of item: «I feel uncertain about most of my action »), Self-criticism (example of item: «I have difficulty forgiving myself when my performance is not flawless»), and Socially-prescribed perfectionism (example of item: «People are disappointed in me whenever I don’t do something perfectly»). Narcissistic Perfectionism includes items of four facets of the original version: Other-oriented perfectionism (example of item: «I expect those close to me to be perfect»), Hypercriticism (example of item: «I get frustrated when other people make mistakes»), Entitlement (example of item: «I am entitled to special treatment»), and Grandiosity (example of item: «I am the absolute best at what I do»). The psychometric properties of the Italian version of the BTPS will be analyzed in the present study. The item of the original version of the BTPS were translated thought the back-translation method.

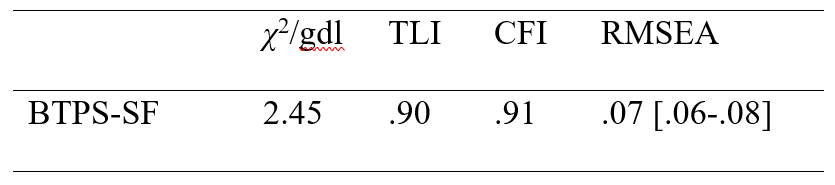

Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMRS; Frost et al., 1990). The Italian version (Di Fabio & Saklofske, in press) of the FMRS-R is compose of 35 items with response format on Likert scale from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree. The scale permits to detect six dimensions: Concern over mistakes (example of item: «If I fail at work/school, I am a failure as a person»); Doubts about actions (example of item: «I usually have doubts about the simple everyday things I do»); Parental expectations (example of item: «My parents wanted me to do the best at everything»); Parental criticism (example of item: «I never felt like I could meet my parents’ standards»); Personal standards (example of item: «If I do not set the highest standards for myself, I am likely to end up a second-rate person»); Organization (example of item: «Organization is very important to me»). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient are: .87 for Concern over mistakes; .88 for Doubts about actions; .88 for Parental expectations; .81 for Parental criticism; .89 for Personal standards; .86 for Organization; .88 for the total score.

Procedure

The scale were administered to university students in a group by trained psychologists in agreement with the requirements of privacy and informed consent of Italian law (Law Decree DL-196/2003). The order of administration was counterbalanced to control the effects of presentation order.

Data analysis

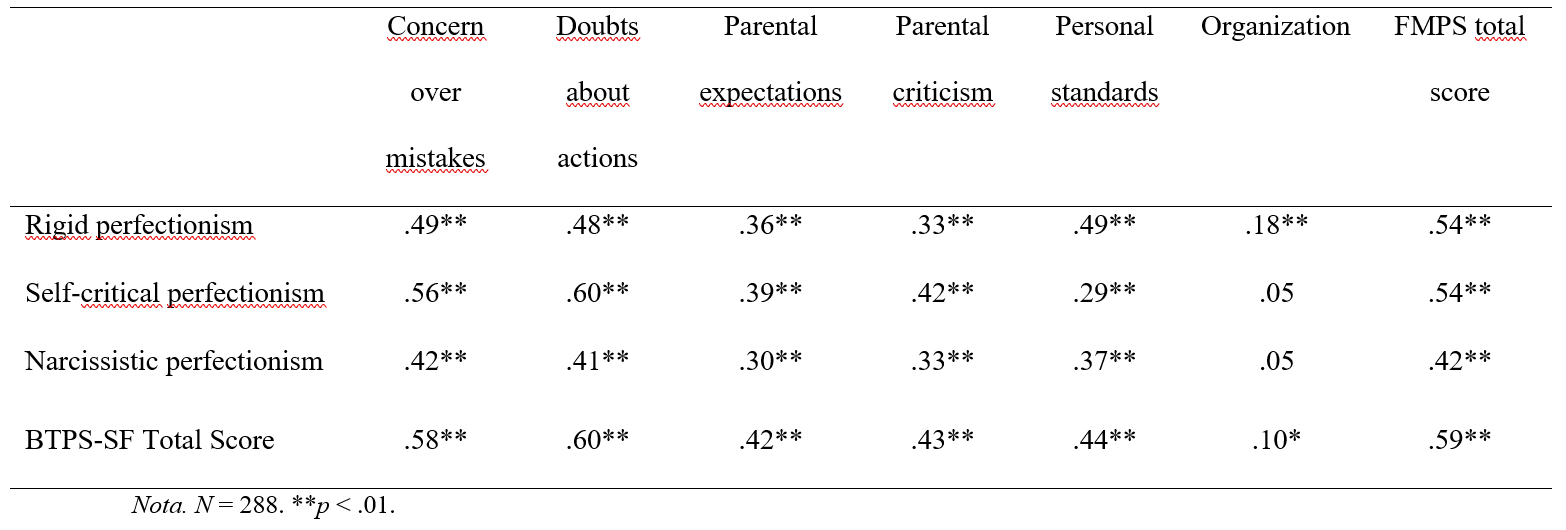

The factorial structure of the Italian short form of the Big-Three Perfectionism Scale (BTPS-SF) was evaluated through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) with AMOS using maximum likelihood method. Different indices was used to estimate the fit of empirical data to the theoretical model: the ratio between chi-square and degree of freedom (χ2/df), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Values of the ratio between chi-square and degree of freedom (χ2/gdl) included between 1 and 3 are considered indicators of a good adaptation. For the TLI (Bentler & Bonnet, 1980; Hu & Bentler 1999), values greater than .90 indicate a good fit. Regarding the CFI, values greater than .90 are considered good (Bentler & Bonnet, 1980). Values of the RMSEA less than .08 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993) are indices of a good fit (Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Muller, 2003; Steiger, 1990). The reliability of this Italian short form of the BTPS was verified using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Construct validity was verified through correlations of the Italian short form of the Big-Three Perfectionism Scale with the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMRS; Frost et al., 1990).

Results

To verify the three-dimensional structure (18 items with six items for each dimensions) of the Italian short form of the BTPS we carried out a Confirmatory Factor Analysis. The indices of Goodness of Fit are reported in Table 1.

Table 1 – Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Goodness of Fit (N = 288)

Regarding reliability the Cronbach’s alphas are: .83 for Rigid perfectionism, .88 for Self-critical perfectionism, .83 for Narcissistic perfectionism, .89 for the total score.

Regarding construct validity correlations are reported in Table 2.

Table 2 – Correlations of BTPS-SF with FMPS

Discussion

The aim of this study was to offer a first contribution to the validation of the Italian short form of the Big-Three Perfectionism Scale (BTPS-SF). The fit of the three-dimensional model was tested through Confirmatory Factor Analysis. The reliability of the scale was verified through Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and resulted good. The correlations between the Italian short form of the Big-Three Perfectionism Scale (BTPS-SF) and the the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMRS; Frost et al., 1990) used to verify construct validity are positive and thus in the expected direction. These correlations showed a satisfactory construct validity of the scale with reference to the effected measures.

Notwithstanding the results of the present study showed that the Italian short form of the Big-Three Perfectionism Scale (BTPS-SF) represents a valid and reliable instrument to detect perfectionism in the Italian context, it is necessary to highlight the limitation to have examined the psychometric properties of the scale only with university students of the University of Florence. Future research should therefore expand to participants from different parts of Italy. This study could be also replicated in other countries, to confirm the cross-cultural significance of the short form of the scale.

Despite the limitations showed above, the Italian short form of the Big-Three Perfectionism Scale (BTPS-SF) appeared as an instrument able to detect perfectionism in the Italian context. The availability of this scale opens new and promising perspectives for research and intervention in relation to this construct since this scale permits to detect three principal factors of perfectionism (rigid perfectionism, self-critical perfectionism, and narcissistic perfectionism) and it is also the first and only scale that comprises a measure of narcissistic perfectionism.

References

Bentler, P. M., & Bonnet, D. C. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588-606.

Blankstein, K. R., & Dunkley, D. M. (2002). Evaluative concerns, self-critical, and personal standards per- fectionism: A structural equation modeling strategy. In G. L. Flett & P. L. Hewitt (Eds.), Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 285-315). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136-162). Newsbury Park, CA: Sage.

Di Fabio, A. & Saklofske, D. H. (in press). Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMRS): First contribution to the Italian version. Counseling. Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni.

Dunkley, D. M., Blankstein, K. R., Halsall, J., Williams, M., & Winkworth, G. (2000). The relation between perfectionism and distress: Hassles, coping, and perceived social support as mediators and moderators. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47, 437-453.

Dunkley, D. M., Blankstein, K. R., Masheb, R. M., & Grilo, C. M. (2006). Personal standards and evaluative concerns dimensions of “clinical” perfectionism: A reply to Shafran et al. (2002, 2003) and Hewitt et al. (2003). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 63-84.

Dunkley, D. M., Zuroff, D. C., & Blankstein, K. R. (2003). Self-critical perfectionism and daily affect: Dispositional and situational influences on stress and coping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 234-252.

Flett, G. L., Sherry, S. B., Hewitt, P. L., & Nepon, T. (2014). Understanding the narcissistic perfectionists among us: Grandiosity, vulnerability, and the quest for the perfect self. In A. Besser (Ed.), Handbook of psychology of narcissism: Diverse perspectives (pp. 43-66). New York, NY: Nova Science.

Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 449-468.

Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 456-470.

Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (2004). Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS): Technical manual. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1-55.

Nealis, L. J., Sherry, S. B., Lee-Baggley, D. L., Stewart, S. H., & Macneil, M. A. (2016). Revitalizing narcissistic perfectionism: Evidence of reliability and validity of an emerging construct. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38, 493-504. doi:10.1007/s10862-016-9537-y

Nealis, L. J., Sherry, S. B., Sherry, D. L., Stewart, S. H., & Macneil, M. A. (2015). Towards a better understanding of narcissistic perfectionism: Evidence of factorial validity, incremental validity, and mediating mechanisms. Journal of Research in Personality, 57, 11-25.

Rice, K. G., Ashby, J. S., & Slaney, R. B. (2007). Perfectionism and the five-factor model of personality. Assessment, 14, 385-398.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Muller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and goodness-of-fit models. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8, 23-74.

Smith, M. M., Saklofske, D. H., Stoeber, J., & Sherry, S. B. (2016). The Big Three Perfectionism Scale: A new measure of perfectionism. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 34(7), 670-687.

Sherry, S. B., Gautreau, C. M., Mushquash, A. R., Sherry, D. L., & Allen, S. L. (2014). Self- critical perfectionism confers vulnerability to depression after controlling for neuroticism: A longitudinal study of middle-aged, community-dwelling women. Personality and Individual Differences, 69, 1-4.

Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioural Research, 25, 173-180.

Stoeber, J., Sherry, S. B., & Nealis, L. J. (2015). Multidimensional perfectionism and narcissism: Grandiose or vulnerable? Personality and Individual Differences, 80, 85-90.

Stoeber, J., & Otto, K. (2006). Positive conceptions of perfectionism: Approaches, evidence, challenges. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 295-319.