Immigration is one of the main features of European societies. Immigrant families pursue better economic conditions and refugee families often escape from conflicts and violence (Hall, Porche, Grossman, & Smashnaya, 2015). Migration offers financial possibilities and routes to educational opportunities for children (Hagelskamp, Suárez‐Orozco, & Hughes, 2010). Immigrant/refugee youth and their families often experience social and socio-economic problems (Hall et al., 2015) and face many challenges with regard to language, differing arrays of acculturation, and language learning of the host country (Morse, 2005). They may often experience difficulties in school concerning the equilibrium between family and home values and school values (Rotich, 2011; Takanishi, 2004).

Since 2011, the European Commission has highlighted the fact that the future of European people should be based on sustainable and inclusive growth (Di Fabio, 2017), enhancing the value and effectiveness of education and training systems in Europe. It may be valuable to promote successful lifelong learning, social integration, personal development and employability (European Commission, 2016). The psychological well-being of immigrant students is affected by the degree to which the schools and local communities in their country of destination support them in facing the different obstacles that they encounter in order to be successful at school and build a new life (OECD, 2009, 2015). Policy makers need to pay attention to supporting children, especially immigrant ones, both in their education and integration into society, enhancing their well-being, and later their employability, and also to improve the development of a skilled workforce capable of contributing to society and adapting to continuous transitions and challenges (European Commission, 2013; Sirius Network, 2017). The importance of focusing on immigrant inclusion at primary school level is thus understandable. The LEND A HAND project seeks to answer this challenge.

LEND A HAND project description

The LEND A HAND project intends to contribute to social inclusion of immigrant and refugee students in primary schools by undertaking a holistic intervention at three levels: a) school level, b) policy level, c) learning - teaching level. This project will put the findings at the three levels into practice while developing an action plan to be disseminated to policy makers. It also intends to develop curricula and train teachers who work in schools with immigrant students on how to incorporate social inclusion principles into their lesson plans. This project also aims to develop a toolkit for primary school teachers to use in their classes and encourage them to pilot social inclusion teaching for six months throughout the project. Another aim of this project is to develop migrant-friendly school networks and guidelines, where it will be possible to share recommendations, regulations, tools and extra-curricular activities for schools in order to transform them into socially inclusive institutions. Finally, this project aims to contribute to inclusive education while strengthening the profile of teachers and supporting schools to tackle issues faced by immigrant students such as early drop out or failure.

This project is being carried out transnationally as in all three countries there is a need to ensure successful inclusion of migrant children in schools. In the LEND A HAND project there are three universities (Gazi University, Ankara, Turkey, applicant; University of Florence, Florence, Italy, partner; Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, partner), a consulting company (Pi Pozitif Danismanlik, Ankara, Turkey) and a public body (Ankara Milli Egitim Mudurlugu, Ankara, Turkey). All partners have been strategically chosen as they are experienced institutions in terms of leading or participating in the implementation of EU funded projects, including the Erasmus + programme. All partner countries receive migration and face difficulties in ensuring full social inclusion of immigrant children at primary schools.

This paper describes the development of a questionnaire to identify needs in relation to social inclusion of immigrant and refugee students in primary schools and reports the results of the administration of the questionnaire in the three countries involved in the project: Italy, Turkey and Portugal. The development of the questionnaire is included in output 1 O1 – Strategic Action Plan – and was conducted by the University of Florence with support from each partner.

Literature review

An analysis of literature was conducted in order to identify needs in relation to social inclusion of immigrant and refugee students in primary schools. This analysis of literature showed that these needs can be divided into three levels: school level, policy level and learning - teaching level (Carr, 2006; Devine & Kelly, 2006; Duong, Badaly, Liu, Schwartz, & McCarty, 2015; EACEA, 2009; Essomba, Tarrés, & Franco- Guillén, 2017; Fangen, 2006, 2010; Hall et al., 2015; OECD, 2015, 2016; Rousseau Drapeau, Lacroix, Bagilishya, & Heusch, 2005).

Specifically, at a school level, the ways that can be used to promote social inclusion of immigrant children are the following (Carr, 2006; Hall et al., 2015; OECD, 2016): developing a programme of professional development for language support teachers; providing additional support for children regarding social, emotional and behavioural needs; providing information centres for parents (in relation to school choice, enrolment and transfer, contacting schools/teachers, homework etc.); setting up a support service for schools in relation to the inclusion of newcomer children, as for example a Visiting Teacher Service to liaise with parents of newcomer children; having access to funding which allows for the provision of translation and interpreting services; setting up a support service for newcomer children, including school planning expertise for planning an intercultural approach; actions to help teachers to identify students who need language training, for example offering specific tools for language assessment; the availability of specific curricula for immigrant students; hiring bilingual teachers; actions to help teachers to recognise the challenges that immigrant and refugee students and their families are facing, for example offering specific training on diversity and intercultural issues; the availability of an out-of-school time programme (that complements school-based learning by fostering positive socio-emotional and academic outcomes); establishment of support structures (e.g. a ‘buddy’ system) to facilitate integration of newly arrived students; development of actions to build trusting and supportive relations between school personnel and parents; the availability of an anti-bullying framework and actions (to empower students to name and confront all forms of prejudicial and exclusionary behaviour when they arise); courses to promote awareness of cultural diversity without stereotyping; school competitions/games based on multicultural teams; support services for parents in relation to problems regarding social inclusion of immigrant children; support services for teachers in relation to problems regarding social inclusion of immigrant children or relationships with their parents; and psychological support services for parents and teachers in relation to problems regarding social inclusion of immigrant children and relationships with their parents.

At a policy level, the ways in which countries promote social inclusion of immigrant children are the following (EACEA, 2009; OECD, 2015, 2016): communication with immigrant families (for example, publishing information on the school system in the mother tongue of the immigrant family, using an interpreter and resource persons responsible for reception and orientation of immigrant pupils); actions to increase immigrant parents’ awareness of the value of the social inclusion of their children, for example, trained specialists making home visits; providing learning resources and information to families; launching awareness campaigns; providing information to immigrant parents on the schooling options available for their children; actions to help parents to overcome financial and/or logistical barriers to access the school of their choice; actions to build the capacity of all schools attended by immigrant students (supporting school leadership, attracting teachers to schools in need by giving special financial incentives, strengthening teaching capacity etc.); actions to avoid concentrating students with an immigrant background in disadvantaged schools, by, for example, better equipping immigrant parents with information on how to select the best school for their children; actions relative to the formation of mixed classes (mainstream students and immigrant students) to allow immigrant students to develop the linguistic and culturally relevant skills needed to perform well at school; providing extra support and guidance to immigrant parents; establishing pre-primary childhood language programmes for immigrant children in order to favour an early learning of the new language; providing actions of language support for immigrant children within regular classes as soon as they have reached an adequate linguistic level to be included in them; providing actions of extra support and guidance to teachers who have to face the issue of social inclusion of immigrant children; and centres of primary listening for social inclusion of immigrant children (addressed to the whole family).

At a learning/teaching level, two areas can be identified: potential factors that affect learning and social inclusion of immigrant children especially in primary schools (Carr, 2006; Devine & Kelly, 2006; OECD, 2016; Rouseeau et al., 2005) and training needs of teachers for promoting social inclusion of immigrant children in primary school (Carr, 2006; OECD, 2015, 2016). Regarding the first area the following factors emerged (Carr, 2006; Devine & Kelly, 2006; OECD, 2016; Rouseeau et al., 2005): integrating language and subject learning from the earliest years; using programmes tailored to the needs of migrant children, particularly by offering language-development activities; using child friendly materials for teaching their native language; the availability of specific programmes for promoting the scholastic achievement of immigrant students; the availability of specific programmes for preventing emotional and behavioural problems of immigrant students; the availability of specific language courses for immigrant students; the availability of cultural mediators and the availability of language translators. Regarding the second, the following training needs emerged (Carr, 2006; OECD, 2015, 2016): training on intercultural issues; training in the area of teaching in a multicultural or multilingual setting; training on diversity; training on language development; training on tracking students’ progress and adjusting teaching to meet individual students’ needs and resources; training to identify and support immigrant students’ and their families’ needs; training to face prejudices and stereotypes; training to prevent bullying; training to recognise talents in a multicultural perspective; training on guidance for immigrant children; training on career counseling for parents of immigrant children; and training on the sustainability of the personal project for immigrant children and their families.

Aims of the study

This study aimed to develop a questionnaire to identify needs in relation to social inclusion of immigrant and refugee students in primary schools and to carry out needs analysis in the three countries: Italy, Turkey and Portugal, involved in the European project Lend a Hand.

Method

Participants

The questionnaire to identify needs in relation to social inclusion of immigrant and refugee students in primary schools was administered in the three partner countries on primary school teachers. Italy and Turkey administered the questionnaire to 150 primary school teachers and Portugal to 131 primary school teachers.

Measure

A first version of the questionnaire to identify needs in relation to social inclusion of immigrant and refugee students in primary schools was developed on the basis of the literature review. Furthermore, focus groups were conducted to improve this first version of the questionnaire. The University of Florence drew up the template for the focus groups, which it shared with the other partners and revised according to their suggestions. The template enabled a shared guide to be used for the conduction of the focus group in each country and thus generated more reliable results for sharing. On the basis of the results of the focus groups, the University of Florence implemented the second draft of the questionnaire by adding aspects emerging from these focus groups, which were missing in the first version of the questionnaire.

The final version of the questionnaire is composed of the following four parts:

The first part is relative to general information and includes: gender, age, level of education, town, country, organisation, and role.

The second part is relative to possible ways that schools can use to promote social inclusion of immigrant children (31 items).

The third part is relative to possible ways that countries can use to promote social inclusion of immigrant children (22 items).

The fourth part is relative to possible factors that can affect learning and social inclusion of immigrant children in primary schools (17 items), possible training needs teachers can have for promoting social inclusion of immigrant children in primary schools (14 items).

The participants were asked to indicate in the first column how frequently they encountered them in their experience on a five-points scale (1 = Never, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Very often, 5 = Always), and in the second column to indicate how much they are important to promote social inclusion of immigrant children in primary schools on a five-points scale (1 = Nothing, 2 = Not much, 3 = Nor or little, 4 = Enough, 5 = Much).

Procedure

In Italy, the questionnaire was administered in a paper-based format to Italian primary school teachers by trained research assistants, in accordance with the Italian Privacy Law.

In Turkey, the questionnaire was administered in a paper-based format to Turkish primary school teachers by trained research assistants. The questionnaires were conducted with the support of Ankara İl Milli Eğitim Müdürlüğü (Ankara Provincial National Education Directorate).

In Portugal, the questionnaire was administered by trained researchers in accordance with the Ethical Code of Portuguese Psychologists, in both formats: a paper-based version and an online (Google-form) version, to Portuguese school teachers of basic education.

Data analysis

Data analyses were carried out by each of the three countries for the participants. Regarding the procedure for data analysis, the total scores and the mean scores for each item were calculated in relation to the second, third and fourth part of the questionnaire. Then the total scores and the relative mean scores were put in descending order.

Results

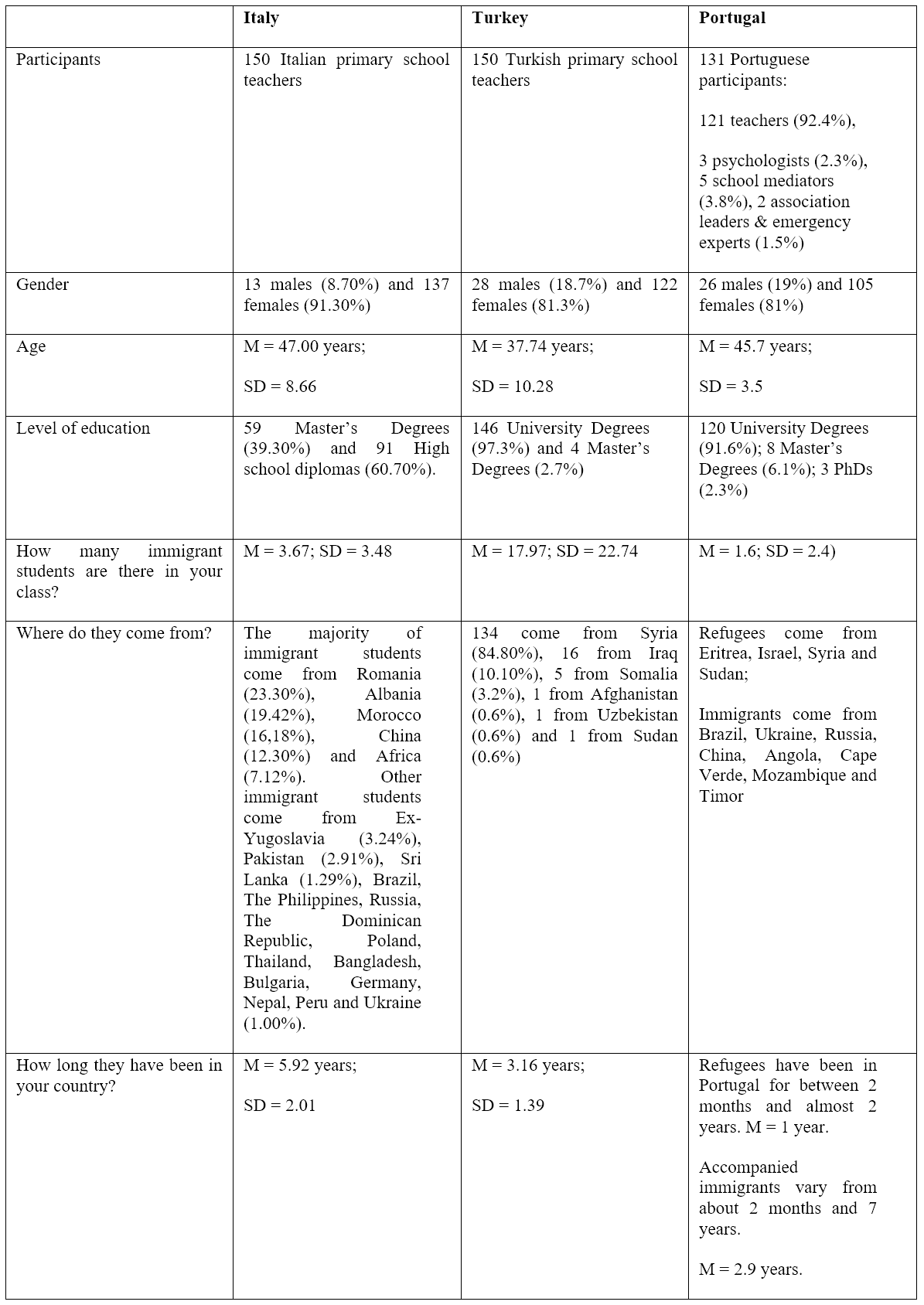

General information about the participants who filled in the questionnaires is given in Table 1.

Table 1. General information about Italy, Turkey and Portugal

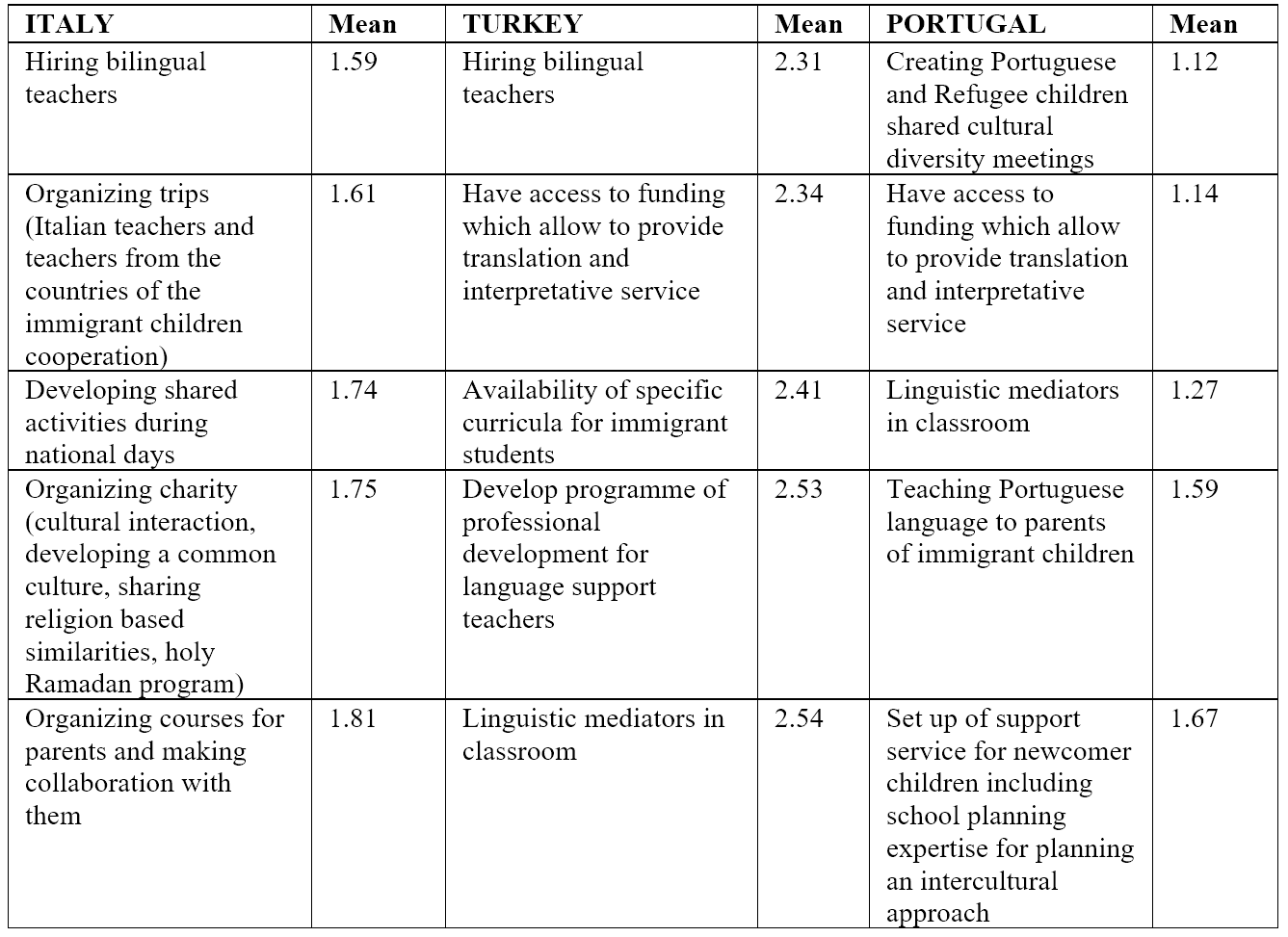

The main results (mean scores) of the perceived lack of ways that schools can use to promote social inclusion of immigrant children are presented in Table 2 for the three partners involved in the project.

Table 2. Average scores of the answers to the FIRST PART a): A LIST OF WAYS SCHOOLS CAN PROMOTE SOCIAL INCLUSION OF IMMIGRANT CHILDREN – Italy, Turkey and Portugal

HOW FREQUENTLY DID YOU ENCOUNTER THEM IN YOUR EXPERIENCE?

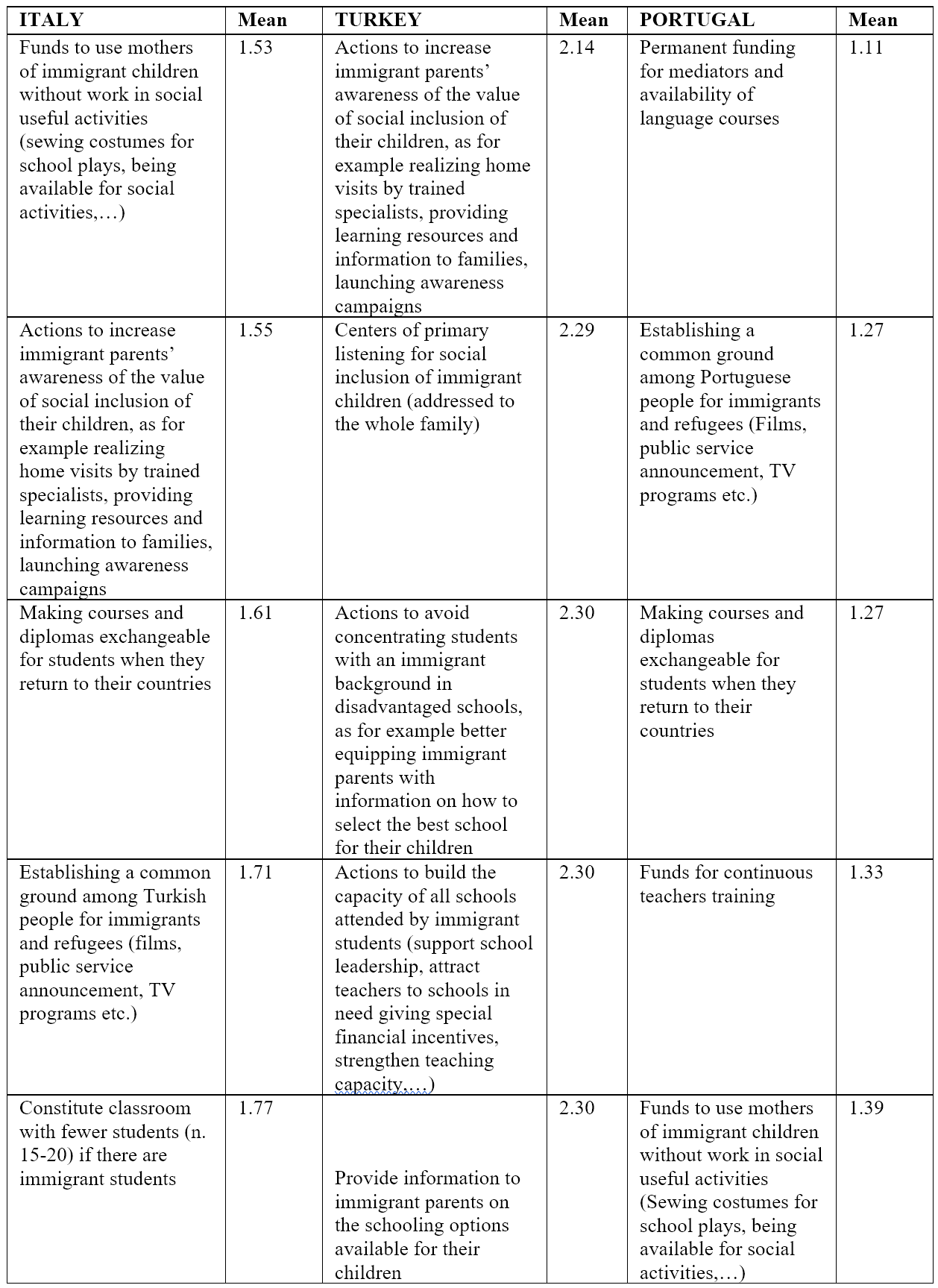

The main results (mean scores) of the perceived lack of ways that countries can use to promote social inclusion of immigrant children are presented in Table 3 for the three partners involved in the project.

Table 3. Average scores of the answers to the SECOND PART a): A LIST OF POSSIBLE WAYS THAT COUNTRIES CAN USE TO PROMOTE SOCIAL INCLUSION OF IMMIGRANT CHILDREN – Italy, Turkey and Portugal

HOW FREQUENTLY DID YOU ENCOUNTER THEM IN YOUR EXPERIENCE?

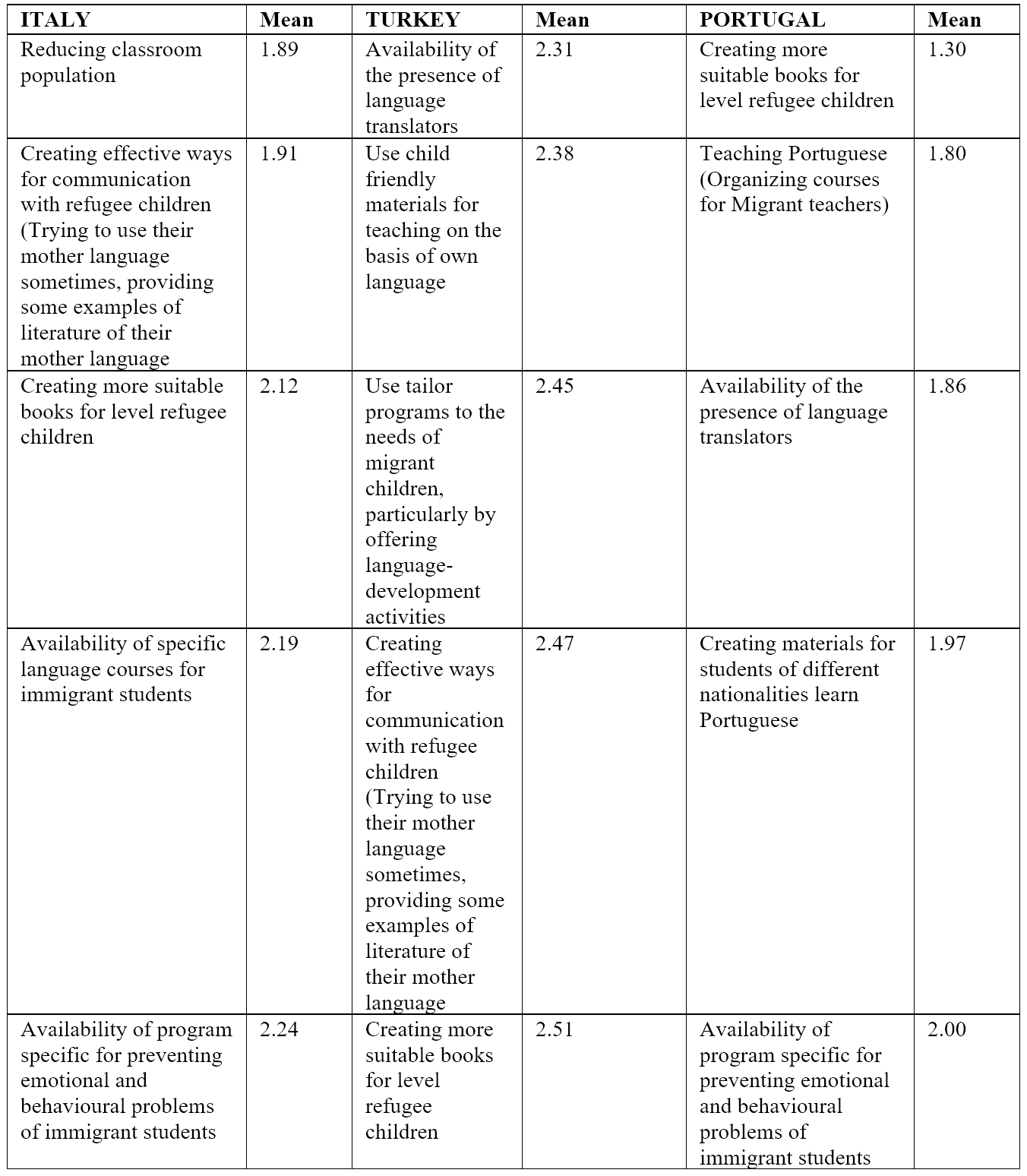

The main results (mean scores) of the perceived lack of factors that can affect learning and social inclusion of immigrant children in primary schools are presented in Table 4 for the three partners involved in the project.

Table 4. Average scores of the answers to the THIRD PART a): A LIST OF POSSIBLE FACTORS THAT CAN AFFECT LEARNING AND SOCIAL INCLUSION OF IMMIGRANT CHILDREN IN PRIMARY SCHOOLS – Italy, Turkey and Portugal

HOW FREQUENTLY DID YOU ENCOUNTER THEM IN YOUR EXPERIENCE?

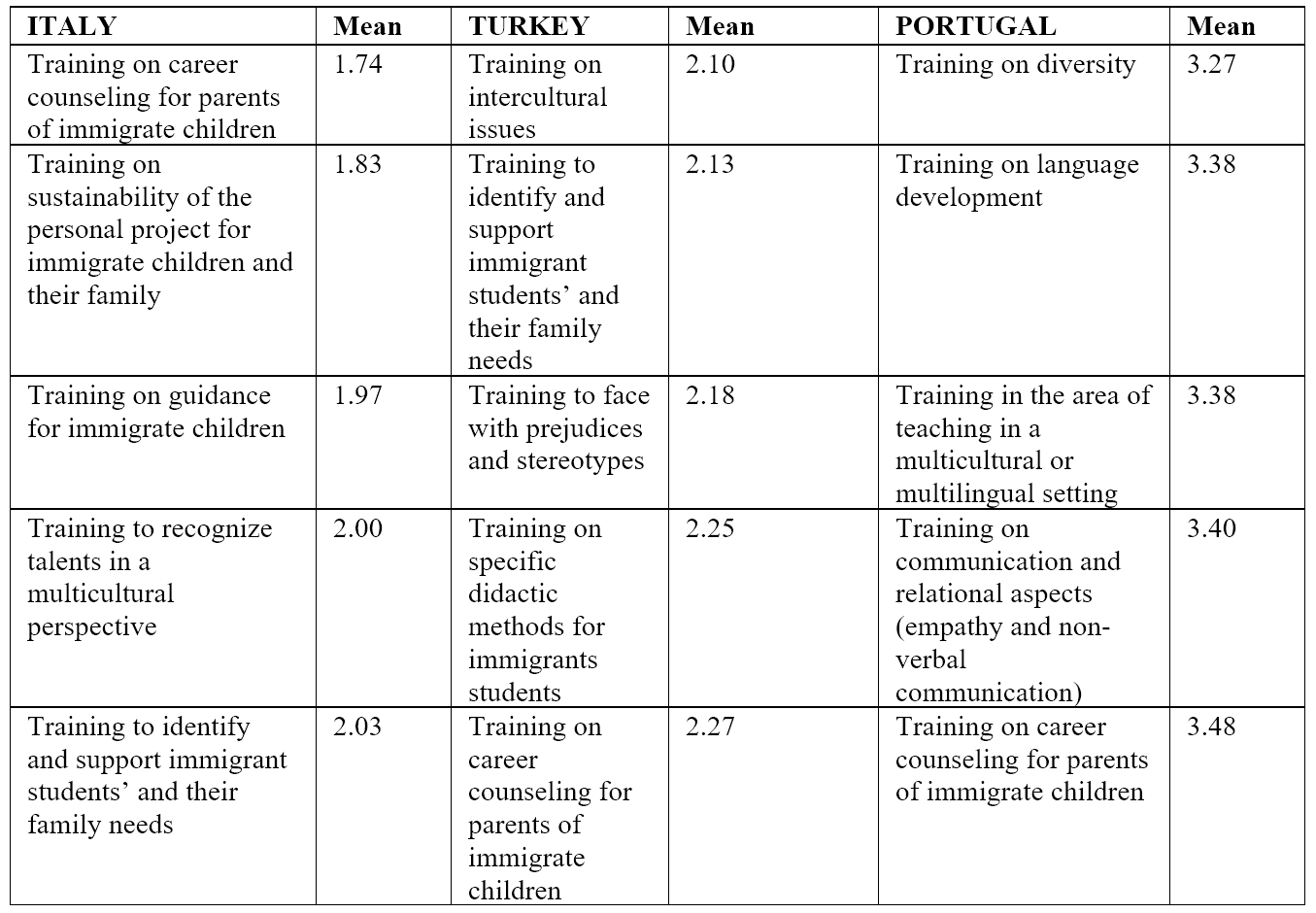

The main results (mean scores) of the possible training needs teachers encountered for promoting social inclusion of immigrant children in primary schools are presented in Table 5 for the three partners involved in the project.

Table 5. Average scores of the answers to the THIRD PART c): A LIST OF POSSIBLE TRAINING NEEDS TEACHERS CAN HAVE FOR PROMOTING SOCIAL INCLUSION OF IMMIGRANT CHILDREN IN PRIMARY SCHOOLS – Italy, Turkey and Portugal

HOW FREQUENTLY DID YOU ENCOUNTER THEM IN YOUR EXPERIENCE?

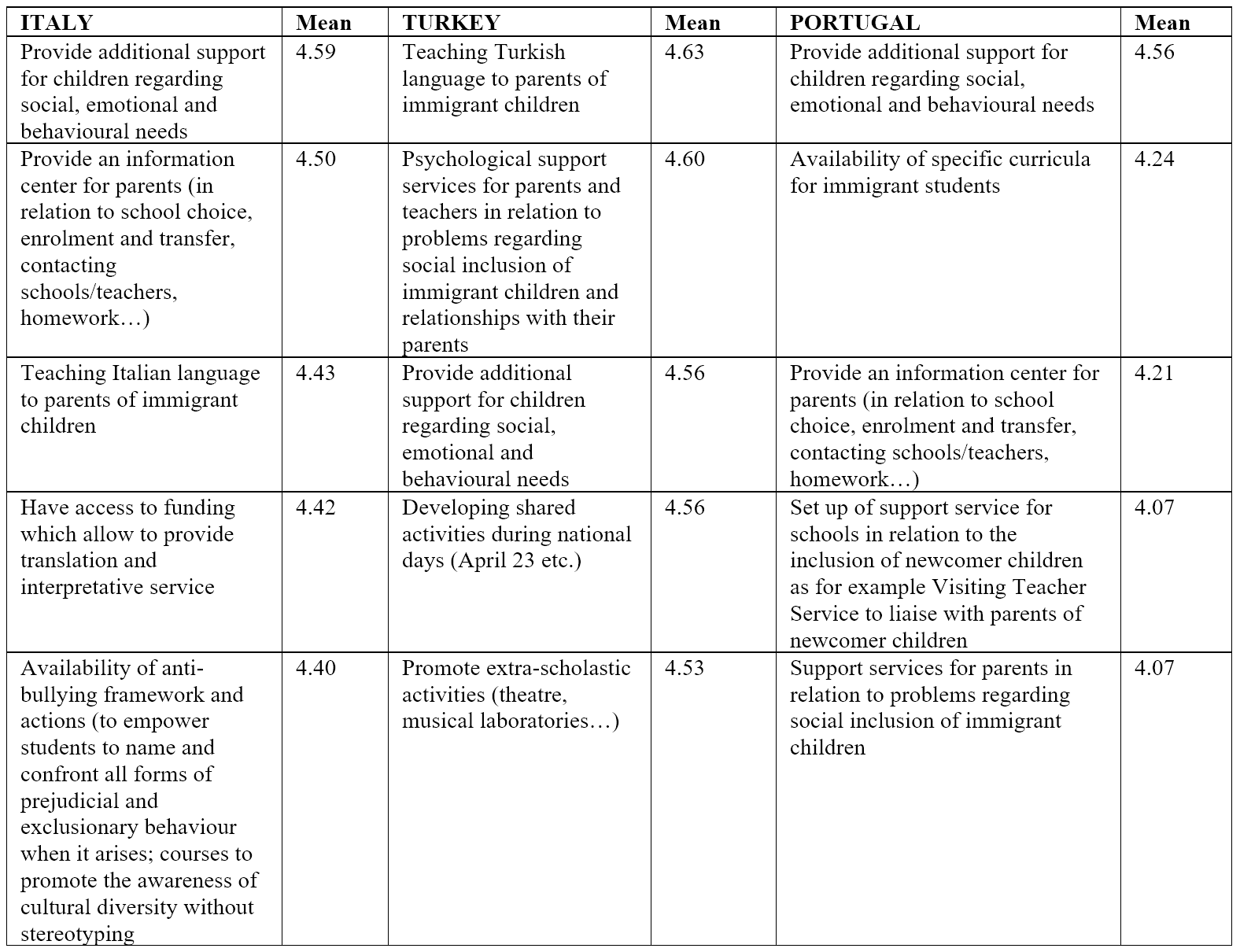

The main results (mean scores) of the principal ways that schools can use to promote social inclusion of immigrant children considered important from the three partners involved in the project are shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Average scores of the answers to the FIRST PART a): A LIST OF POSSIBLE WAYS THAT SCHOOLS CAN USE TO PROMOTE SOCIAL INCLUSION OF IMMIGRANT CHILDREN – Italy, Turkey and Portugal

HOW MUCH IT IS IMPORTANT TO PROMOTE SOCIAL INCLUSION?

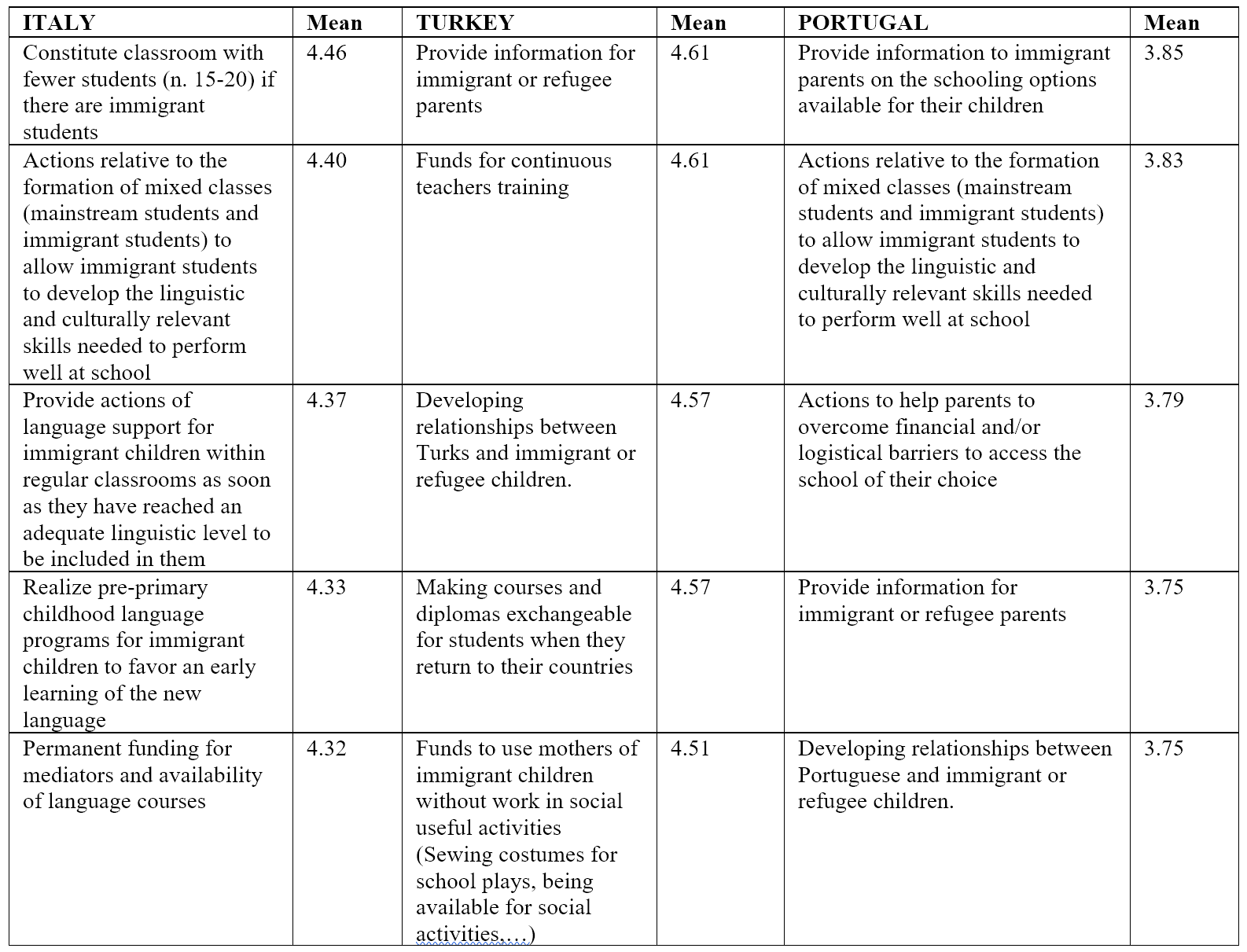

The main results (mean scores) of the principal ways that countries can use to promote social inclusion of immigrant children considered important from the three partners involved in the project are shown in Table 7.

Table 7. Average scores of the answers to the SECOND PART a): A LIST OF POSSIBLE WAYS THAT COUNTRIES CAN USE TO PROMOTE SOCIAL INCLUSION OF IMMIGRANT CHILDREN – Italy, Turkey and Portugal

HOW MUCH IT IS IMPORTANT TO PROMOTE SOCIAL INCLUSION?

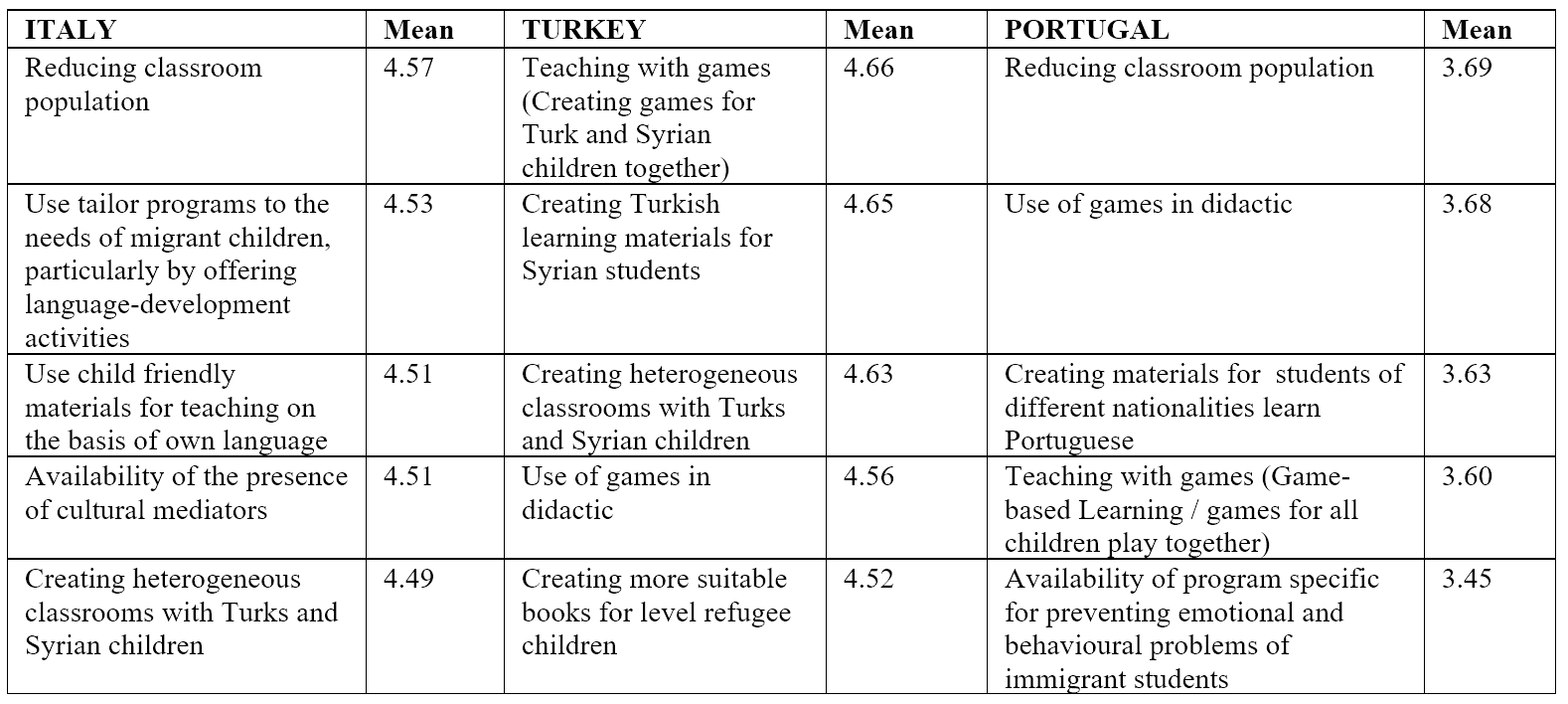

The main results (mean scores) of the main factors that can affect learning and social inclusion of immigrant children in primary schools considered important from the three partners involved in the project are shown in Table 8.

Table 8. Average scores of the answers to the THIRD PART a): A LIST OF POSSIBLE FACTORS THAT CAN AFFECT LEARNING AND SOCIAL INCLUSION OF IMMIGRANT CHILDREN IN PRIMARY SCHOOLS – Italy, Turkey and Portugal

HOW MUCH IT IS IMPORTANT TO PROMOTE SOCIAL INCLUSION?

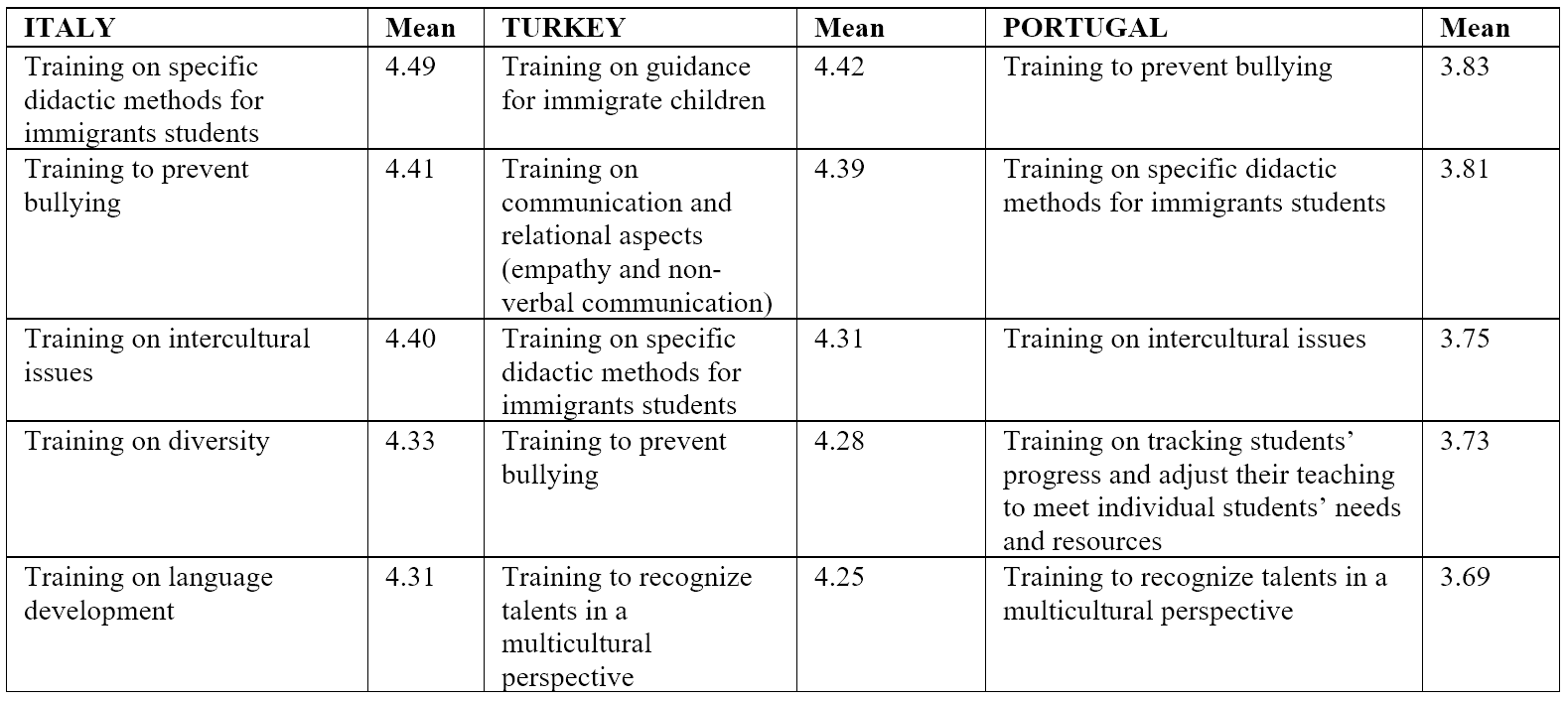

The main results (mean scores) of the principal training needs that the three partners involved in the project think are important for promoting social inclusion of immigrant children are shown in Table 9.

Table 9. Average scores of the answers to the THIRD PART c): A LIST OF POSSIBLE TRAINING NEEDS TEACHERS CAN HAVE FOR PROMOTING SOCIAL INCLUSION OF IMMIGRANT CHILDREN IN PRIMARY SCHOOLS – Italy, Turkey and Portugal

HOW MUCH IT IS IMPORTANT TO PROMOTE SOCIAL INCLUSION?

The analysis carried out in the questionnaire allowed us to define a framework for promoting social inclusion of immigrant children in primary schools.

Analysis of the results of the questionnaires administered in the three countries involved in the “Lend a Hand” project (Italy, Turkey and Portugal) allows us to outline recommendations for policy makers regarding the enhancement of social inclusion of immigrant children in primary schools.

Discussion

The results of the administration of the questionnaire allow us to outline the needs in relation to social inclusion of immigrant and refugee students in primary schools throughout the three countries (Italy, Turkey and Portugal) on three levels: school level, policy level, learning/teaching level.

Concerning the school level, it emerged that it is very important to provide strong support for students regarding social, emotional and behavioural needs, as well as to create psychological support services for parents and teachers in relation to problems regarding social inclusion of immigrant children according to literature (Carr, 2006; Hall et al., 2015; OECD, 2016). The enhancement of relationships between schools and immigrant students’ families through regular meetings and greater coordination between formal and non-formal activities is also underlined, highlighting the possibility to promote social inclusion (Carr, 2006; Hall et al., 2015; OECD, 2016). Furthermore, specific courses to teach the language of the host country both to immigrant students and their parents require special attention, in particular to improve the scholastic performance of immigrant students and their integration into society as underlined in literature (Carr, 2006; Hall et al., 2015; OECD, 2016). Teaching the language of the country that they live in to parents of immigrant children in order to promote language learning in social environments also needs consideration (Carr, 2006; Hall et al., 2015; OECD, 2016).

Furthermore, socio-cultural activities such as out-of-school time programmes must be enhanced for positive socio-emotional and academic outcomes, socialisation with peers, (linguistic, cultural and ethnic) diversity and comprehension. In these terms, promoting extra-curricular activities such as taking refugee students to the theatre or on school trips may facilitate social inclusion of the immigrant students (Carr, 2006; Hall et al., 2015; OECD, 2016).

These are potential ways that may reduce the risk of early school leaving, poverty and social exclusion, the costs for society in relation to lost talents and public expenditure related to social, health and even justice systems, improving the equity of education and access to training resources and the development of children’s potential (Carr, 2006; Hall et al., 2015). The knowledge of different cultures can contribute to the psychological well-being of immigrant students as well as to the degree in which schools and local communities in the host countries support them to deal with the many obstacles they face in succeeding at school and integrating into society (Carr, 2006; Hall et al., 2015).

As for the policy level, the results showed different areas in which countries can intervene to support social inclusion of immigrant children. The first area that emerged is the support area. In fact, it is very important to provide immigrant or refugee parents information on school (options, opportunities, laws etc.) to reduce the barriers that can put many immigrant children at risk of not getting enough education, not choosing their preferred school and curricula, not being able to adapt to school, and experiencing failures. It is also relevant to give information on daily life aspects (e.g. health, economic and bureaucratic aspects) with the increased number of specialised professionals who can enable them to become independent, successful, and productive in the host country (EACEA, 2009; OECD, 2015, 2016). Another area that emerged is the regulatory area, the possibility of forming mixed classes (mainstream students and immigrant students) could be significant, allowing immigrant students to develop the linguistic and culturally relevant skills needed to perform well at school (EACEA, 2009; OECD, 2015, 2016). Moreover, the economic-financial area calls for funds for class mediators, access to school and educational materials, language courses for parents, and continued teacher training (EACEA, 2009; OECD, 2015, 2016). The contribution of countries at a political level is fundamental in promoting the social inclusion of children (EACEA, 2009; OECD, 2015, 2016).

Regarding the learning/teaching level in relation to the factors that can affect learning and of immigrant children in primary schools, it emerged that it is important to take into account a structural aspect related to the creation of small classes with heterogeneous populations in order to facilitate the exchange and sharing of different cultures, communication among students with diverse backgrounds and with teachers, and individualised support. Also the increasing number of tools available to the teachers are relevant, such as didactic games that can fully involve all students in the class, tailored programmes to the needs of immigrant students, offering in particular language-development activities, and new technologies and digital books which can be more easily used by immigrant students. All these aspects can facilitate the learning of immigrant children in primary school and encourage their social inclusion (Carr, 2006; Devine & Kelly, 2006; OECD, 2016; Rouseeau et al., 2005). The didactic area emerged as one of the important training needs teachers may have for promoting social inclusion of immigrant children in primary schools. First of all, teachers need training on specific didactic methodologies for teaching immigrant students and on intercultural issues in order to learn about different cultures, habits, languages, religion etc. Teachers need training on diversity, interculturality and the languages of immigrant students, in order to consider multiculturality as a resource for learning and to be able to handle cultural diversity in the classroom. Moreover, training on the administrative issues of refugee students is an essential need for teachers. Maintenance of training processes should be provided by those responsible. Making teachers aware of the importance of the collaboration of teachers would also facilitate the shared experiences of teachers. All these aspects emerged in literature as an important way of improving the learning of immigrant children and promoting their inclusion in the new country (Carr, 2006; OECD, 2015, 2016). Another important aspect relates to the need of teachers to have training to prevent bullying, helping students to name and confront all forms of prejudicial and exclusionary behaviour when they arise. They also need courses to promote the awareness of cultural diversity without stereotyping and courses for improving their communication with the families of immigrant children. These aspects regard an important relational dimension that is important to consider in order to promote social inclusion of immigrant children (Carr, 2006; OECD, 2015, 2016).

Despite the fact that the study shows the needs in relation to social inclusion of immigrant and refugee students in primary schools throughout the three countries (Italy, Turkey and Portugal) on three levels (school level, policy level, learning/teaching level), it has its limitations. The participants were a limited group of primary school teachers from the three countries (Italy, Turkey and Portugal) and thus they are not representative of all primary school teachers of the three realities. Future research should therefore extend this study to participants from different geographical regions in the three partner countries. This study could be also carried out in other countries for possible comparisons.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the study allowed us to formulate some promising suggestions that could converge in a Strategic Paper for policy makers to promote social inclusion of immigrant children in European countries. Furthermore, regarding counseling, the results of this study suggests the importance of creating also counseling and psychological support services both for children in primary schools and their families in order to encourage their social inclusion at school, in the community and in broader society. New research perspectives for guidance and career counseling psychology are offered.

References

Baganha, M. I. (2009). The Lusophone migratory system: Patterns and trends. International Migration, 47(3), 5-20.

Carr, J. (2006). Newcomer children in the primary education system. I.N.T.O. Service Education. Retrieved from https://www.into.ie/ROI/Publications/NewcomerChildren.pdf

Devine, D., & Kelly, M. (2006). ‘I just don't want to get picked on by anybody’: Dynamics of inclusion and exclusion in a newly multi‐ethnic Irish primary school. Children & Society, 20(2), 128-139.

Di Fabio, A. (2017). The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. In G. Arcangeli, G. Giorgi, N. Mucci, J.-L. Bernaud, & A. Di Fabio (Eds.), Emerging and re-emerging organizational features, work transitions and occupational risk factors: The good, the bad, the right. An interdisciplinary perspective. Research Topic in Frontiers in Psychology. Organizational Psychology, 8, 1534. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01534

Duong, M. T., Badaly, D., Liu, F. F., Schwartz, D., & McCarty, C. A. (2016). Generational differences in academic achievement among immigrant youths: A meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 86(1), 3-41.

EACEA/Eurydice (2009). Integrating immigrant children into schools in Europe: Measures to foster communication with immigrant families and heritage language teaching for immigrant children. Brussels: Eurydice.

Essomba, M. A., Tarrés, A., & Franco- Guillén (2017). N. EU-Ukraine relations in the field of agriculture and food industry. Retrieved from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/529074/IPOL_STU(2014)529074_EN.pdf

European Commission (2008). Education and migration. Strategies for integrating migrant children in European schools and societies. Retrieved from http://www.nesse.fr/nesse/activities/reports/activities/reports/education-and-migration-pdf

European Commission (2013). Study on educational support to newly arrived migrant children. Retrieved from http://bookshop.europa.eu/en/study-on-educational-support-for-newly-arrived-migrant- children-pbNC3112385/

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2016). Structural indicators on early childhood education and care in Europe – 2016. Eurydice Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Fangen, K. (2006). Humiliation experienced by Somali refugees in Norway. Journal of Refugee Studies, 19(1), 69-93.

Hall, G., Porche, M. V., Grossman, J., & Smashnaya, S. (2015). Practices and approaches of out-of-school time programs serving immigrant and refugee youth. Journal of Youth Development, 10(2), 72-87.

Morse, A., Littlefield, L., & Speasmaker, L. (2007). A review of state immigration legislation in 2005. Immigrant Policy Project.

OECD (2010). PISA 2009 Results: Executive Summary. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/46619703.pdf

OECD (2015). Helping immigrant students to succeed at school – and beyond. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/education/Helping-immigrant-students-to-succeed-at-school-and-beyond.pdf

OECD (2016). Programme for international student assessment (PISA) results from PISA 2015. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/pisa/PISA-2015-Italy.pdf

Rotich, J. (2011). Mentoring as a springboard to acculturation of immigrant students into American schools. Journal of Case Studies in Education, 1, 1.

Rousseau, C., Drapeau, A., Lacroix, L., Bagilishya, D., & Heusch, N. (2005). Evaluation of a classroom program of creative expression workshops for refugee and immigrant children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(2), 180-185.

Sirius Network (2017). Statement on the revision of the Key Competences Framework. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/education/files/kcr-consultation-responses/kcr-consultation-406-sirius_en.pdf

Suárez‐Orozco, C., & Todorova, I. L. (2003). The social worlds of immigrant youth. New Directions for Student Leadership, 2003(100), 15-24.

Takanishi, R. (2004). Leveling the playing field: Supporting immigrant children from birth to eight. The future of Children, 61-79.