Vol. 17, n. 1, febbraio 2024

strumenti

Facilitating Conditions for School Motivation Scale: Validazione della Versione Italiana

Fatima Abu Hamam, Chiara Bassi, Cassandra Wubbels, Alessandro Mancini, Martina Pastorelli, Francesco Tommasi e Riccardo Sartori1

Sommario

Il presente articolo riporta lo studio di validazione di una versione italiana ridotta della Facilitating Conditions for School Motivation scale. Nello specifico, lo studio propone una versione ridotta a 15 item comprendente tre fattori decisivi nell’attitudine degli adolescenti verso la formazione e l’apprendimento: il primo legato al bagaglio di valori posseduto dallo studente; il secondo comprendente la componente affettiva; il terzo relativo al supporto ricevuto dalle relazioni con genitori, pari e insegnanti. Per la validazione si è dunque realizzato un modello a tre fattori associato alle condizioni facilitanti o inibenti menzionate prima. È stato coinvolto un campione eterogeneo di studenti provenienti da diversi percorsi educativi e i dati sono stati raccolti in un periodo di nove mesi nel Nord Italia. Le analisi mostrano come la scala sia in grado di intercettare le condizioni che influiscono sulla motivazione degli studenti nei confronti della loro carriera formativa. Tale misura si rileva essere utile nel contesto di ricerca e nella realizzazione di interventi per la promozione della motivazione a scuola.

Parole chiave

Condizioni facilitanti, Validazione italiana, Studenti, Motivazione.

INSTRUMENTS

Facilitating Conditions for School Motivation Scale: Validation of the Italian Version

Fatima Abu Hamam, Chiara Bassi, Cassandra Wubbels, Alessandro Mancini, Martina Pastorelli, Francesco Tommasi, and Riccardo Sartori2

Abstract

The present study reports the validation of the Italian short version of the Facilitating Conditions for School Motivation Scale. The scale comprises 15 items which reflect three determining factors that contribute to students’ school motivation, the first of which relates to students’ values. The second includes the affective component while the third considers the support received from relationships with parents, peers and teachers.

We tested a three-factor model associated with the facilitating or inhibiting conditions on a heterogeneous group of adolescents from different educational backgrounds, whose data were collected over a period of nine months in Northern Italy. The analysis reveals that the short version intercepts the conditions that influence the students’ motivation towards their educational career. Our findings provide implications for research and practice for understanding and promoting students’ motivations at school.

Keywords

Facilitating conditions, Italian validation, Students, Motivation.

Introduction

Understanding and investigating school motivation in young adults is of paramount importance as it serves as a foundational pillar in shaping their educational experiences and future trajectories. Delving into the intricacies of what drives motivation at this crucial stage not only unveils the dynamics of academic engagement but also lays the groundwork for interventions that can positively impact personal development and lifelong learning. With respect to this, numerous studies highlight the impact of students’ personal goals and internal motivational factors on school outcomes (Gugliandolo et al, 2021; Otani, 2020; Samuel & Burger, 2020). Moreover, McInerney (1992) suggests that internal elements (e.g. affect and value) and external factors (e.g. parents, teachers, and peer support) can crucially affect the translation of internal motivations into behaviour and significantly influence students’ motivation and behaviour (Bradley et al., 2021; Sethi & Scales, 2020; Wu et al., 2022).

Considering the literature, there is wide evidence on the connection between students’ perceptions of support from parents, teachers, and peers and various aspects of their motivation and academic performance (Lerner, 2022; Shukla, 2015; Wu et al., 2022). First, parents play a crucial role in students’ education, with parental involvement being a strong predictor of academic success (Cui et al., 2021; Hill & Craft, 2003). Second, as they progress in age, peers become increasingly influential in shaping adolescents’ thoughts, emotions, and actions (Ragelienė & Grønhøj, 2020) with positive peer interactions being associated with academic performance and the development of positive self-concepts (Fredricks et al., 2004; O’Brien et al., 2021; Wentzel et al., 2004). Lastly, teachers are also a prominent source of motivation of adolescents by influencing students’ academic perceptions and behaviours (Amtu et al., 2020; Scales et al., 2020). Perceived support from teachers is strongly associated with prosocial behaviour, educational aspirations, intrinsic values, and enhanced self-concept (Kındap-Tepe et al., 2021). Moreover, from the relational level to the individual level, students’ affect towards school is also crucial for school motivation and academic achievement (Camacho-Morles et al., 2021; Halimi, 2021; MacCann et al., 2020). Similarly, the perceived value of school reveals a crucial aspect influencing motivation. The extent to which students’ affect to education and value of going to school plays a significant role in either fostering or inhibiting motivation to achieve or stay in school (Burns et al., 2020; Honicke et al., 2020; Zysberg & Schwabsky, 2021).

Exploring the factors that influence school motivation, it becomes crucial to provide scholars and practitioners with effective measurement tools for identifying the keys to fostering an interest in learning. Following this impetus, the aim of the present paper is to present the Italian validation of a short version of the Facilitating Conditions for School Motivation Scale (FCSM) (McInerney et al., 2005). This scale is designed to measure factors that can influence young adults’ school motivation. In this study, we specifically test a three-factor model associated with the facilitating or inhibiting conditions mentioned earlier. These factors include values, affects, and a third factor related to the relational condition represented by the support of parents, peers and teachers. Validating this scale in an Italian context could enhance targeted interventions, ultimately promoting positive school motivation and shaping educational experiences and future trajectories.

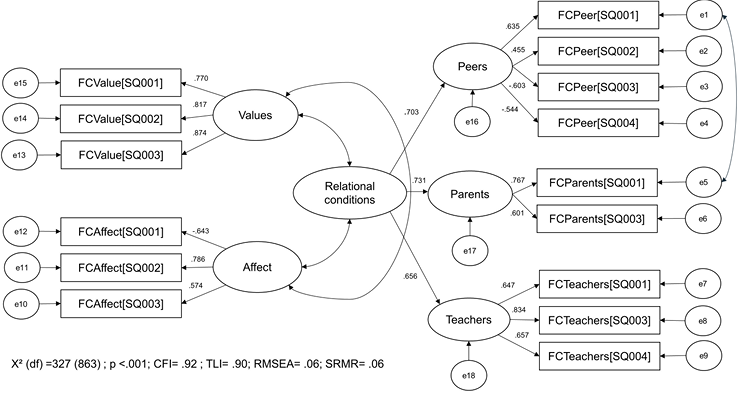

Figure 1

Path diagram of the CFA’s model with fit indices.

Method

Participants & Procedure

To validate the Italian short version of the FCSM, we involved 698 students (63% males, average age of 17, SD = 2.5) in a cross-sectional study. Data were collected from a group of students coming from different educational streams (high schools, preliminary vocational education, and training) in the North of Italy over a period of 9 months. The study was conducted following the ethical principles of Helsinki and all participants, and their parents, were informed about the purposes of the project and given a statement ensuring the confidentiality of their individual results (World Medical Association, 2013).

Measures

We measured using the 15 items from McInerney and colleagues’ (2005) original FCSM scale, which consisted of 26 items. Respondents are asked to report their agreement on a 5-point Likert-type scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) to evaluate the statements. These 15 items reflect five specific factors, namely a) value, measuring the perceived value of schooling, b) affect, exploring feelings toward schooling (3 items), c) peer positive, evaluating the perceived positive contributions of peers to perceptions of schooling (4 items), d) parent positive, examining the perceived positive contributions and psychological support from parents (2 items) and e) teachers support, assessing positive support from teachers toward schooling and further education (3 items). The FCSM Scale was translated into Italian for validation (see Table 1). The scale reported an internal reliability coefficient of Cronbach’s α = .80.

Data analysis

Preliminary analysis included estimates of alpha reliability. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using SPSS version 22. The goodness of fit was guided by chi-square (χ^2) statistics; incremental fit indices, such as the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI); and absolute fit indices, including the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Analyses applied maximum likelihood estimation to assess the fit of a three-factor model.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

A path diagram of the models and their fit indices is presented in Figure 1. As indicated above, we tested a hypothesized three-factor FCSM structure. The CFA reveals robust estimates with significant statistical strength across all indicators. Standardized factor loadings ranged from .45 to .87, each confirmed by significance p-values well below the .001 threshold.

Fit indices revealed a good correspondence between the hypothesized model and the observed data, as shown by a CFI of .92, surpassing the conventional cut-off of .90. A TLI of .93, is slightly over the recommended threshold of .90, showing reasonable level of fit; A RMSEA of .06, lying within the conventional cut-off of .08, demonstrates a good fit for the model. Moreover, the SRMR value of .06, below the threshold of .08, supports the adequacy of the model fit.

Discussion

In this study, our primary objective was to validate the Italian version of the FCSM scale using a sample of 698 students across different educational streams in Northern Italy, including high school, preliminary vocational education, and training. Our hypothesized three-factor model was tested through CFA, which demonstrated a robust alignment between the data and our theoretical framework. The favourable fit indices from CFA, coupled with satisfactory internal reliability, substantiate the validity of the three-factor FCSM scale. These results provide evidence to the idea that the conditions influencing school motivation are intertwined with values, affect, and a third relational aspect where significant others (peers, teachers and parents) can either facilitate or inhibit students’ achievement motivation and behaviour. Consequently, the FCSM scale emerges as a reliable tool for assessing school motivation conditions among Italian adolescents. The implications of this study are noteworthy. The validated Italian version of the FCSM scale equips educators, researchers and policymakers with a reliable instrument to assess and comprehend the conditions influencing adolescents’ school motivation. Acknowledging the significance of values, affect, and relational conditions, interventions can be crafted to strengthen these factors, fostering positive school motivation.

As with all empirical studies, the present has some limitations that must be acknowledged. Expanding the study to a more diverse and representative sample would enhance the external validity of our findings. Additionally, incorporating assessments for convergent and discriminant validity would further fortify the overall validity of the FCSM scale, offering a more comprehensive understanding of its psychometric properties. Subsequent research should further refine and broaden the scale’s applicability, ensuring its effectiveness across diverse educational contexts.

References

Amtu, O., Makulua, K., Matital, J., & Pattiruhu, C. M. (2020). Improving Student Learning Outcomes through School Culture, Work Motivation, and Teacher Performance. International Journal of Instruction, 13(4), 885-902. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2020.13454a

Bradley, G. L., Ferguson, S., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2021). Parental support, peer support, and school connectedness as foundations for student engagement and academic achievement in Australian youth. In M. J. Furlong, R. Gilman, & S. Huebner (Eds.), Handbook of Positive Youth Development: Advancing Research, Policy, and Practice in Global Contexts (pp. 219-236). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70262-5_15

Burns, R. A., Crisp, D. A., & Burns, R. B. (2020). Re-examining the reciprocal effects model of self-concept, self-efficacy, and academic achievement in a comparison of the cross-lagged panel and random-intercept cross-lagged panel frameworks. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(1), 77-91. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12265

Camacho-Morles, J., Slemp, G. R., Pekrun, R., Loderer, K., Hou, H., & Oades, L. G. (2021). Activity achievement emotions and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 33(3), 1051-1095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09585-3

Cui, Y., Zhang, D., & Leung, F. K. (2021). The influence of parental educational involvement in early childhood on 4th grade students’ mathematics achievement. Early Education and Development, 32(1), 113-133. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2019.1677131

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59-109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Gugliandolo, M. C., Cuzzocrea, F., Costa, S., Soenens, B., & Liga, F. (2021). Social support and motivation for parenthood as resources against prenatal parental distress. Social Development, 30(4), 1131-1151. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12521

Halimi, F., AlShammari, I., & Navarro, C. (2021). Emotional intelligence and academic achievement in higher education. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 13(2), 485-503. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.1252

Hill, N. E., & Craft, S. A. (2003). Parent-school involvement and school performance: Mediated pathways among socioeconomically comparable African American and Euro-American families. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 74-83. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.74

Honicke, T., Broadbent, J., & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2020). Learner self-efficacy, goal orientation, and academic achievement: Exploring mediating and moderating relationships. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(4), 689-703. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1685941

Kındap-Tepe, Y., & Aktaş, V. (2021). The mediating role of needs satisfaction for prosocial behavior and autonomy support. Current Psychology, 40, 5212-5224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00466-9

Lerner, R. E., Grolnick, W. S., Caruso, A. J., & Levitt, M. R. (2022). Parental involvement and children’s academics: The roles of autonomy support and parents’ motivation for involvement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 68, 102039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2021.102039

MacCann, C., Jiang, Y., Brown, L. E., Double, K. S., Bucich, M., & Minbashian, A. (2020). Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(2), 150–186. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000219

McInerney, D. M. (1992). Cross-cultural insights into school motivation and decision making. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 13(2), 53-74. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000219

McInerney, D. M., Dowson, M., & Yeung, A. S. (2005). Facilitating conditions for school motivation: Construct validity and applicability. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65(6), 1046–1066. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405278561

O’Brien, K. H., Wallace, T., & Kemp, A. (2021). Student perspectives on the role of peer support following concussion: Development of the success peer mentoring program. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 30(2S), 933-948. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00076

Otani, M. (2020). Parental involvement and academic achievement among elementary and middle school students. Asia Pacific Education Review, 21(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-019-09614-z

Ragelienė, T., & Grønhøj, A. (2020). The influence of peers’ and siblings’ on children’s and adolescents’ healthy eating behavior: A systematic literature review. Appetite, 148, 104592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104592

Samuel, R., & Burger, K. (2020). Negative life events, self-efficacy, and social support: Risk and protective factors for school dropout intentions and dropout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(5), 973–986. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000406

Scales, P. C., Van Boekel, M., Pekel, K., Syvertsen, A. K., & Roehlkepartain, E. C. (2020). Effects of developmental relationships with teachers on middle-school students’ motivation and performance. Psychology in the Schools, 57(4), 646-677. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22350

Sethi, J., & Scales, P. C. (2020). Developmental relationships and school success: How teachers, parents, and friends affect educational outcomes and what actions students say matter most. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 63, 101904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101904

Shukla, S. Y., Tombari, A. K., Toland, M. D., & Danner, F. W. (2015). Parental support for learning and high school students’ academic motivation and persistence in mathematics. Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, 5(1), 44-56. https://doi.org/10.5539/jedp.v5n1p44

Wentzel, K. R., Barry, C. M., & Caldwell, K. A. (2004). Friendships in middle school: Influences on motivation and school adjustment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(2), 195-203. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.2.195

World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191-2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053

Wu, Y., Hilpert, P., Tenenbaum, H., & Ng-Knight, T. (2022). A weekly-diary study of students’ schoolwork motivation and parental support. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(4), 1667-1686. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12532

Zysberg, L., & Schwabsky, N. (2021). School climate, academic self-efficacy, and student achievement. Educational Psychology, 41(4), 467-482. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1813690

APPENDIX

Table 1

Italian Version of Facilitating Conditions for School Motivation Scale.

|

Values |

|

|

item 2 |

Se ottengo buoni risultati nello studio ho più probabilità di ottenere un buon lavoro |

|

item 3 |

Credo che sia davvero importante ottenere buoni risultati nello studio |

|

item 4 |

Ottenere buoni risultati nello studio è davvero importante per il mio futuro |

|

Affects |

|

|

item 1 |

Non amo in alcun modo studiare o imparare (r) |

|

item 2 |

Mi piace impegnarmi nello studio |

|

item 3 |

Gli argomenti oggetto di studio mi interessano |

|

Peers |

|

|

item 1 |

I miei amici dicono che dovrei proseguire gli studi |

|

item 2 |

I miei amici sostengono che dovrei lasciare la scuola e usufruire dell’assistenza statale |

|

item 3 |

I miei amici dicono che dovrei abbandonare gli studi e trovare un lavoro (r) |

|

Parents |

|

|

item 3 |

Mia madre crede che io sia abbastanza intelligente per proseguire gli studi |

|

item 2 |

Se decidessi di proseguire gli studi, mio padre mi incoraggerebbe |

|

item 2 |

Mio padre crede che dovrei lasciare gli studi il prima possibile per andare a lavorare (r) |

|

Teachers |

|

|

item 1 |

Alcuni insegnanti mi incoraggiano ad andare bene a scuola |

|

item 2 |

Se decidessi di andare all’università, i miei insegnanti mi incoraggerebbero |

|

item 3 |

Alcuni dei miei insegnanti mi dicono che sono abbastanza intelligente per andare all’università |

Vol. 17, Issue 1, February 2024