Vol. 14, n. 2, giugno 2021

STUDI E RICERCHE

Pensare al futuro dopo la pandemia

Il ruolo del coraggio nella mediazione tra Paura del Covid-19 e Pessimismo

Andrea Zammitti1, Rita Zarbo2, Giuseppe Santisi3 e Paola Magnano4

Sommario

Tra gli effetti della pandemia da Covid-19 c’è la paura. Questa emozione è legata a conseguenze negative: pensare al proprio futuro lavorativo è diventato difficile. Tuttavia, il coraggio può supportare gli studenti nella progettazione della propria carriera. Il presente studio è stato suddiviso in due fasi. Nella prima abbiamo voluto indagare, qualitativamente, come gli studenti universitari pensano sarà il loro futuro. Nella seconda abbiamo ipotizzato che il coraggio possa mediare nella relazione tra paura del Covid-19 e pessimismo. Il campione è costituito da 209 studenti universitari di età compresa tra 19 e 24 anni (M = 20.99; DS = 1.39). I risultati hanno confermato le ipotesi e mostrato che le preoccupazioni degli studenti sono maggiormente riferite ai rapporti sociali.

Parole chiave

Coraggio, Pessimismo, Covid-19, Carriera, Pandemia.

STUDIES AND RESEARCHES

Thinking about the future after the pandemic

The mediating role of courage in the relationship between fear of Covid-19 and pessimism

Andrea Zammitti5, Rita Zarbo6, Giuseppe Santisi7 and Paola Magnano8

Abstract

Among the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic is fear. This emotion is linked to negative consequences: thinking about one’s working future has become difficult. However, courage can support students in planning their careers. The present study was divided into two phases. In the first, we investigated, through qualitative research, how university students imagine their future. In the second phase, we hypothesized that courage could mediate in the relationship between fear of Covid-19 and pessimism. The participants were 209 university students aged between 19 and 24 (M = 20.99; SD = 1.39). The results confirmed the hypotheses and showed that students’ concerns are more related to social relationships.

Keywords

Courage, Pessimism, Covid-19, Career, Pandemic.

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to abrupt changes in the lives of people around the world, not only socially but also in terms of work and career planning. The global economy has suffered such a severe setback that it is considered «the worst economic recession since the Great Depression» (Gopinath, 2020). Moreover, the pandemic situation has led to the intensification of remote working methods, sometimes never experienced before, which have required people to be flexible and adaptable, and the forced closures due to the succession of different lockdowns have caused stalemate situations and high uncertainty about the future. In addition, the pandemic situation has sparked a new fear, the fear of Covid, affecting various domains, bodily, interpersonal, cognitive, and behavioural ones (Schimmenti, Billieux, & Starcevic, 2020), and is related to states of panic, anxiety and stigma (Ahorsu et al., 2020). Notwithstanding the fact that it performs an adaptive function, which has allowed humans to survive threats (Presti et al., 2020), fear can reach levels that trigger other negative emotions (Cui et al., 2016; Lang & McTeague, 2009). Very recent studies (Ahorsu et al., 2020; Harper et al., 2020) have explained that fear of coronavirus is caused by uncertainty about how bad its impact can be.

Among the psychological correlates, the psychological process of having repeated negative and catastrophic thoughts (Davey & Wells, 2008), related to worrying and pessimism, seem to be involved in the fear of Covid-19 (Mertens et al., 2020). Jovančevic and Milićević (2020), exploring the relationship between fear of Covid-19 and — among others — pessimism, found that pessimists tend to exhibit higher levels of fear. In fact, when people think about their future, they draw positive or negative inferences depending on what they are experiencing (Scheier & Bridges, 1995), and the construction of a situation can determine in part as much its failure as its success, being related to both the fear of failure and the desire to succeed (Norem & Cantor, 1986). Planning one’s career with high, positive, optimistic expectations helps individuals to put more effort and commitment into achieving their future goals (Ginevra et al., 2017); conversely, pessimistic visions of the future may discourage proactive behaviour (Hecht, 2013).

For this reason, during the pandemic, an element of literature turned a watchful eye to the importance of positive psychology and to several of its important dimensions (Karataş, Uzun, & Tagay, 2021). Among the latter, we focused on the role of courage as a dimension capable of allowing individuals to behave despite fear (Norton & Weiss, 2009). Courage helps people to resist external problems and to maintain a desire to do things (Magnano et al., 2019). Moreover, courage plays the role of a protective factor in dealing with risky and stressful conditions, in affecting coping strategies (Magnano et al., 2017), in making career choices, and in planning career paths despite current fears (Watson, 2003).

Research Aims

Given the premises, we investigated how university students imagine their future. We used a qualitative approach in this regard.

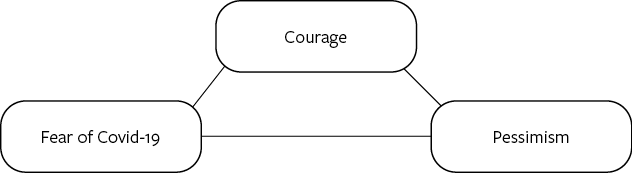

In a second phase, we hypothesized that courage could mediate in the relationship between fear of Covid-19 and pessimism regarding one’s future work. The hypothesized model is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1

Hypothesized model.

Method

Participants and research design

The research study involved 209 participants, university students (M = 36; F = 173), aged from 21 to 29 years (M = 20.99; DS = 1.39). Participants were recruited on a voluntary basis from universities in southern Italy, using convenience sampling.

Measures

To assess Fear of Covid-19, Pessimism and Courage, the instruments described below were used. The reliability of the measures was considered acceptable with a minimum Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.60 (Taber, 2018; Di Nuovo, 2008).

Fear of Covid-19

To assess Fear of Covid-19 we used the Multidimensional Assessment of Covid-19-Related Fears (MAC-RF; Schimmenti et al., 2020). The scale comprises 8 items on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 = «Very unlike me» to 4 = «Very like me». A sample item is «I don’t trust my own body to protect me against the coronavirus infection». Cronbach’s alpha of the study sample was 0.73.

Pessimism

We used 6 items of Vision About Future (VAF; Ginevra et al., 2017) to assess Pessimism. Participants responded using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = «It does not describe me at all» to 5 = «It describes me very well». A sample item is «It will be hard to find a job that really suits me». Cronbach’s alpha of the study sample was 0.87.

Courage Measure

The Courage Measure (CM; Norton & Weiss, 2009; Ginevra et al. 2020) comprises 6 items and participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = «Never» to 7 = «Always». A sample item is «Even if I feel terrified, I will stay in that situation until I have done what I need to do». Cronbach’s alpha of the study sample was 0.85.

To investigate how students perceive the future, we asked them to answer the following question: Do you think people’s way of life will change in the future? If so, how?

Procedure

Participants were asked to fill in an online survey after giving consent to the processing of their personal data. Anonymity was guaranteed.

Data collection was carried out in January 2021. In Italy, lockdown restrictions have been applied since early March 2020. Starting from September 2020, the system of restrictions adopted by the government has followed the so-called colour system for each region: red (strong lockdown measures), orange (medium lockdown measures) or yellow (minor lockdown measures). At the time of data collection, southern Italy was in the red or orange zone. The survey was approved by the ethical committees of the universities involved and the research followed the ethical rules of the Italian Psychological Association.

Data Analysis

We used qualitative and quantitative analysis, using NVivo 12.0 (QSR International, 2018) and JASP 0.14.1 software (JASP Team, 2020).

Specifically, in the first phase, we conducted qualitative analyses. In this case, we used an inductive type of approach, starting from the data without having any starting hypotheses (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). This procedure is based on the Grounded Theory Method (GTM), which allows you to explore a concept by making the theory emerge from the data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). NVivo 12.0 software helped us to identify the words most used by respondents and to identify the supply nodes.

In the second phase, we conducted mediation analysis using JASP 0.14.1 software, placing fear of Covid-19 as an independent variable and pessimism as a dependent variable; courage was posited as a mediating variable.

Results

Phase 1

In this phase, a Word Frequency query was used to list the most frequent words. This query is generally used to identify possible themes, and to find the most frequently occurring concepts (QSR International, 2014). Table 1 shows the results of this query.

Table 1

Word Frequency.

|

Word |

Count |

Word |

Count |

|

|

People |

64 |

Masks |

9 |

|

|

To live |

34 |

Freedom |

7 |

|

|

Contacts |

26 |

Virus |

7 |

|

|

Fear |

21 |

Hygiene |

7 |

|

|

Society |

19 |

Tecnology |

7 |

|

|

Normality |

14 |

Anxiety |

6 |

|

|

Future |

13 |

Attention |

5 |

|

|

Smart-working |

13 |

Difficulty |

5 |

|

|

Pandemic |

12 |

Worse |

5 |

|

|

Time |

10 |

Relationships |

5 |

|

|

Hugs |

10 |

To kiss |

4 |

|

|

Distance |

10 |

Healt |

4 |

Based on word frequency, we codified the following nodes, shown in table 2: 1) Worries for social relationships: it refers to concerns related to contact with other people and the deterioration of social relationships. This node includes answers such as «It will be difficult to go back to living as before. The fear of creating gatherings will continue to exist and also the fear of going to crowded places like clubs» or «Yes. Social relationships will get worse, we will be afraid of returning to normality and hugging and kissing others when it all ends». 2) Technological changes: it refers to the prediction of technological changes, in particular the use of technology applied to work and social situations. This category includes answers such as «There will be a significant increase in the use of programs and apps to communicate remotely» or «It will change radically, for example, because some jobs will only exist in remote mode (smart working)». 3) Positive changes: some students identified the possibility that the pandemic will bring about positive changes. For example, «People will be able to appreciate even the things they previously considered normal daily routine» or «People will become more responsible and be grateful every day for what they have, because, as we have seen and experienced, life and the world can totally change in one day». 4) Psychological problems: this node includes the responses of those who identified the psychological problems underlying society after the pandemic. For example, answers such as «There will be more phobias and isolation» or «In my opinion, there will be more anxiety in a greater number of subjects, young people who will become anxious and paranoid adults». 5) Physical distancing, hygiene, masks: this node includes the answers of those who believe that after the pandemic society will continue to adopt typical lockdown measures, such as social distancing, hygiene or the use of masks. For example, answers such as «There will be more respect for one’s own and others’ hygiene» or «I believe that social distancing measures will remain, at least in public places» fall into this node. 6) Economical problems: it refers to concerns about economic problems in the future. For example, answers such as: «in the future, it will be necessary to take into account the economic difficulties of the people» or «it will be a future in which there will be greater economic disparity». 7) Some students believe that there will be no change after the pandemic. We have classified these responses into another node called No change.

Table 2

Nodes and References.

|

Nodes |

References |

|

Worries for social relationships |

62 |

|

Technological changes |

28 |

|

Positive changes |

28 |

|

Psychological problems |

25 |

|

Physical distancing, hygiene, masks |

23 |

|

Economical problems |

14 |

|

No change |

45 |

Phase 2

We first evaluated the normality of the distributions of the variables using the Shapiro-Wilk Test. The results are shown in table 3, together with the mean and the standard deviation of each variable.

Table 3

Descriptive Statistics.

|

Fear of Covid-19 |

Pessimism |

Courage |

|

|

Mean |

23.976 |

11.325 |

27.971 |

|

Std. Deviation |

5.510 |

4.453 |

6.498 |

|

Shapiro-Wilk |

0.989 |

0.909 |

0.987 |

|

P-value of Shapiro-Wilk |

0.105 |

< .001 |

0.045 |

The non-normal distribution (p <0.05) of pessimism and courage justified the use of the Spearman’s coefficient to study the relationships between the variables, including age. Although weak, some significant correlations emerged. Pessimism correlates positively with fear of Covid-19 and with age and negatively with courage. Fear of Covid-19 negatively correlates with courage. The results are shown in table 4.

Table 4

Correlations between the variables of the study and Age (Spearman’s Coefficient).

|

Variable |

Age |

Fear of Covid-19 |

Pessimism |

Courage |

|

|

1. Age |

Spearman’s rho |

— |

|||

|

p-value |

— |

||||

|

2. Fear of Covid-19 |

Spearman’s rho |

-0.074 |

— |

||

|

p-value |

0.288 |

— |

|||

|

3. Pessimism |

Spearman’s rho |

0.154 |

0.203 |

— |

|

|

p-value |

0.026 |

0.003 |

— |

||

|

4. Courage |

Spearman’s rho |

-0.090 |

-0.190 |

-0.331 |

— |

|

p-value |

0.193 |

0.006 |

< .001 |

— |

Then, we verified the mediation hypothesis: fear of Covid-19 has both a direct (β = .13, p < .001) and indirect (β = .05, p < .001) relationship with pessimism; the indirect relationship is mediated by courage. The results are reported in table 5.

Table 5

Effect of Fear of Covid-19 on Pessimism through Courage (standardized β).

|

Path |

Indirect Effect |

Direct Effect |

Total Effect |

|||

|

β |

C.I. 95% |

β |

C.I. 95% |

β |

C.I. 95% |

|

|

Fear of COVID-19 – Courage–Pessimism |

0.05 |

0.01 – 0.09 |

0.13 |

0.02 – 0.23 |

0.17 |

0.07 – 0.28 |

Discussion

The study aimed to explore fears and worries in a group of emerging adults during the Covid-19 pandemic. Data analysis, conducted with qualitative and quantitative methods, shows the following results: firstly, the first node that identifies fears and worries refers to social relationships and social contacts. The second node regards technological changes and, in general, the use of technology in daily life. The third node, on the contrary, identifies positive changes subsequent to the pandemic. The fourth one is defined as psychological problems, identifying the increasing feelings of discomfort and psychological distress experienced. The fifth includes worries related to typical lockdown measures to prevent the spread of the virus. Moreover, there are a consistent number of respondents that do not expect any significant change to be brought about due to the pandemic period.

Regarding fears of social relationships and social contacts, probably a reflection on the distancing measures taken by different governments to contain the pandemic is required. If, on the one hand, these distancing measures have stopped the infection from spreading further, on the other, they have created a strong sense of fear in physical and relational contacts with others (Schimmenti, Billieux, & Starcevic, 2020). They have also shifted the different areas of life (personal, social, work, learning, shopping) from offline to online modes, generating an accelerated diffusion of emerging digital technologies as a result (Vargo et al., 2021). In the opposite direction, a group of responses reported positive perception regarding the experience of lockdown, explained through the possibility of finding a new meaning in life. Previous studies have demonstrated that when encountering situations that have the potential to challenge or stress their global meaning, individuals appraise the situations and assign meaning to them; furthermore, the distress initiates a process of meaning making, through which individuals attempt to restore a sense of the world as meaningful and their own lives as worthwhile; this process, when successful, leads to better adjustment to the stressful event (Park, 2010). The node named psychological problems regards the most frequent consequences of a very stressful situation, such as the pandemic is. These results are confirmed by numerous studies conducted during the last year on the population worldwide. For example, in a study involving the Chinese population after two weeks of quarantine, the psychological impact on them was rated as moderate or brief by 53.8% (Wang et al., 2020): moderate to severe depressive symptoms were reported by 16.5% of participants, anxiety by 28.8%, and stress by 8.1%. Moreover, other researchers underlined the risk of a considerable increase in anxiety and depressive symptoms among people who do not have pre-existing mental health conditions (Cullen, Gulati, & Kelly, 2020). Furthermore, from a psychological perspective, young adults have shown high levels of psychological symptoms in response to the Covid-19 outbreak (Lai et al., 2020). In terms of age, young adults (18-30) have higher levels of stress, anxiety and depression in comparison with the elderly (60-82 years) (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020).

Regarding worries related to the typical lockdown measures implemented to prevent the spread of the virus, maybe these could be related to compliance in following them: many changes in lifestyle are required for social distancing, impacting on the development of mental disorders (Rogowska, Kuśnierz, & Bokszczanin, 2020). The main changes in lifestyle and everyday habits required to avoid infections are the use of face masks outside the home, avoidance of touching one’s face with one’s hands, and social distancing (Oral & Gunlu, 2021). People who try to maintain social distance do not want to go out, causing loneliness, low mood, and stress (Lewis, 2020). Regarding expectations of no significant changes, these responses could probably be related to the exceptionality of the occurrence of the pandemic event: the respondents could be led to think that such an unusual event will be extremely unlikely to recur in the future and that, therefore, once the pandemic is over, everything and everybody will return to the same life as before.

Secondly, quantitative data analysis shows that pessimism tends to increase with increasing age, and as expected, it is negatively related to courage and positively to fear of Covid-19.

An increase of pessimism is particularly relevant in emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2011), which is defined as the age of instability, characterized by frequent changes in job, educational directions and core dimensions of life. Emerging adults are focused on the exploration of their life options; the way they deal with this increase in opportunities and the decrease in immediate responsibilities is largely differentiated among diverse individuals: as highlighted by Murphy and colleagues (2010), many emerging adults view the multitude of options as exciting and empowering, while others become psychologically paralyzed, indolent, and in extreme cases, depressed. Moreover, the current socio-economic conditions, characterized by a recession due to the restrictions in life and work imposed by the management of the Covid-19 pandemic, amplify feelings related to living in a risky society (Beck, 2014), in which risk, uncertainty and frequent changes are prominent characteristics; subsequently, the increasing negative perception of the future could affect feelings of discomfort and hopelessness (Nota & Rossier, 2015).

Finally, through mediation analysis we found that courage plays a partially mediating role in the relationship between fear of Covid-19 and pessimism. Courage is a behavioural construct characterized by the presence of fear, the intentionality of the action, and a significant goal (Norton & Weiss, 2009); as highlighted previously, courage helps people to deal with external problems despite being fearful and to maintain the desire to persevere in reaching significant goals (Magnano et al., 2019). Previous research has shown that courage as a psychological resource can be an adaptive behaviour that supports individuals in facing the demands associated with risky and stressful conditions, in daily life and work contexts (Santisi et al., 2020). Literature on the relationship between courage and pessimism is scarce; however, in a very recent study, Ginevra et al. (2020) found that high levels of courage were related to lower levels of pessimism, consistently with Hannah, Sweeney and Lester (2010) model, which proposes that courage is significantly related to personal strengths and resources (optimism, hope, pessimism, future orientation, and resilience).

The present study offers a point of view on emerging adults’ perceptions and feelings during the pandemic conditions. Despite the capacity to passively adapt to restrictions imposed by government, young adults are not immune to developing psychological consequences: worries and fears in the social dimension of their life, worries about social contacts, the excessive use of technology to replace daily activities that could not be carried out in the usual ways, and psychological distress are the main effects detected through our study. Moreover, fears related to the spread of the contagion have the result of affecting and developing a pessimistic orientation; courage can mediate this relation, acting as a protective factor to the risk of increasing a pessimistic orientation towards life.

However, the results of the present study should be read considering its limitations: first of all, the cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow for causal relationships between the variables to be established; secondly, the exclusive use of self-report measures represents a limit in the detection of psychological dimensions; thirdly convenience sampling, not adequately balanced in terms of gender, does not allow the generalizability of the results to the population.

A defining characteristic of the counseling psychology profession is to focus on the positive (Magyar-Moe & Lopez, 2008), the strengths, resources, and potential of the client (American Psychological Association [APA], 1999; Gelso, Nutt Williams, & Fretz, 2014; Savickas, 2003). The improvement of positive resources, such as courage, can support effective coping strategies under stressful conditions, reducing the risks of psychological distress and of psychosocial maladjustment. As Duan and Zhu (2020) highlighted, specialized psychological intervention for Covid-19 should be dynamic and flexible enough to adapt quickly to the different phases of the pandemic.

Moreover, in difficult economic times, it can be even more difficult for graduates to enter the workforce (Koen, Klehe, & Van Vianen, 2012), and it has been estimated that it takes twice as long to find a job than in better economic times (ILO, 2011).

For these reasons, counseling interventions that take into account the changing context can be carried out to strengthen not only courage but also other important dimensions in order to support young people entering the world of work (Zammitti, Zarbo & Magnano, 2018).

Bibliography

Ahorsu, D. K., Lin, C., Imani, V., Saffari, M., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2020). The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8

American Psychological Association (1999). Archival description of counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 27, 589-592.

Arnett, J. L. (Ed.) (2011). Bridging cultural and developmental approaches to psychology: New syntheses in theory, research, and policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beck, U. (2014). Ulrich Beck: Pioneer in cosmopolitan sociology and risk society. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Cui, H., Zhang, J., Liu, Y., Li, Q., Li, H., Zhang, L., Hu, Q., Cheng, W., Luo, Q., Li, J., Li, W., Wang, J., Feng, J., Li, C., & Northoff, G. (2016). Differential alterations of resting-state functional connectivity in generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder. Human brain mapping, 37(4), 1459-1473. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23113

Cullen, W., Gulati, G., & Kelly, B. D. (2020). Mental health in the Covid-19 pandemic. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(5), 311-312. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa110

Davey, G. C. L., & Wells, A. (Eds.) (2008). Worry and its psychological disorders: Theory, assessment and treatment. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Di Nuovo, S. (2008). Misurare la mente: i test cognitivi e di personalità. Roma-Bari: Laterza.

Duan, L, Zhu, G. (2020). Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(4), 300-302. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30073-0.

Gelso, C. J., Nutt Williams, E., & Fretz, B. (2014). Counseling psychology (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Ginevra, M. C., Santilli, S., Camussi, E., Magnano, P., Capozza, D., & Nota, L. (2020). The Italian adaptation of courage measure. International Journal of Educational and Vocational Guidance, 20, 457-475. doi: 10.1007/s10775-019-09412-4

Ginevra, M. C., Sgaramella, T. M., Ferrari, L., Nota, L., Santilli, S., & Soresi, S. (2017). Visions about future: A new scale assessing optimism, pessimism, and hope in adolescents. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 17(2), 187-210. doi: 10.1007/s10775-016-9324-z

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago, IL, USA: Aldine.

Gopinath, G. (2020). The Great lockdown: Worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. IMFBlog. Retrieved from https://blogs.imf.org/2020/04/14/the-great-lockdown-worst-economic-downturn-since-the-great-depression/

Hannah, S. T., Sweeney, P. J., & Lester, P. B. (2010). The courageous mind-set: A dynamic personality system approach to courage. In C. S. Pury, S. J. Lopez, C. S. Pury, & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), The psychology of courage: Modern research on an ancient virtue (pp. 125-148). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association

Harper, C. A., Satchell, L. P., Fido, D., & Latzman, R. D. (2020). Functional fear predicts public health compliance in the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1-14. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00281-5

Hecht, D. (2013). The neural basis of optimism and pessimism. Experimental Neurobiology, 22(3), 173-199.

Hsieh, H. F. & Shannon, S. E. (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277-1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

ILO. (2011). Global unemployment trends for youth: 2011 update. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

JASP Team. (2020). JASP (Version 0.14.1) [Computer software].

Jovančević, A., & Milićević, N. (2020). Optimism-pessimism, conspiracy theories and general trust as factors contributing to COVID-19 related behavior. A cross-cultural study. Personality and individual differences, 167, 110216. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110216

Karataş, Z., Uzun, K., & Tagay, Ö. (2021). Relationships between the Life Satisfaction, Meaning in Life, Hope and Covid-19 Fear in Turkish Adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 778. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633384

Koen, J., Klehe, U. C., & Van Vianen, A. E. (2012). Training career adaptability to facilitate a successful school-to-work transition. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(3), 395-408. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.10.003

Lai, J., Ma, S., Wang, Y., Cai, Z., Hu, J., Wei, N., et al. (2020). Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open 3, e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

Lang, P. J., & McTeague, L. M. (2009). The anxiety disorder spectrum: Fear imagery, physiological reactivity, and differential diagnosis. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 22(1), 5-25. doi: 10.1080/10615800802478247

Lewis, K. (2020). Covid-19: Preliminary data on the impact of social distancing on loneliness and mental health. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 26(5), 400-404. doi: 10.1097/PRA.0000000000000488

Magnano, P., Paolillo, A., Platania, S., & Santisi, G. (2017). Courage as a potential mediator between personality and coping. Personality and individual differences, 111, 13-18. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.01.047

Magnano, P., Santisi, G., Zammitti, A., Zarbo, R., & Di Nuovo, S. (2019). Self-perceived employability and meaningful work: the mediating role of courage on quality of life. Sustainability, 11(3), 764. doi: 10.3390/su11030764

Magyar-Moe, J. L., & Lopez, S. J. (2008). Human agency, strengths-based development, and psychological well-being. In W. B. Walsh (Ed.), Biennial review of counseling psychology (pp. 157-177). New York, NY: Routledge.

Mertens, G., Gerritsen, L., Duijndam, S., Salemink, E., & Engelhard, I. M. (2020). Fear of the coronavirus (COVID-19): Predictors in an online study conducted in March 2020. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 74, 102258. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102258

Murphy, K. A., Blustein, D. L., Bohlig, A. J., & Platt, M. G. (2010). The college to career transition: An exploration of emerging adulthood. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88(2), 174-181. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00006.x

Norem, J. K., & Cantor, N. (1986). Anticipatory and post hoc cushioning strategies: Optimism and defensive pessimism in “risky” situations. Cognitive therapy and research, 10(3), 347-362. doi: 10.1007/BF01173471

Norton, P. J., & Weiss, B. J. (2009). The role of courage on behavioral approach in a fear-eliciting situation: A proof-of-concept pilot study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(2), 212-217. doi. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.07.002

Nota, L., & Rossier, J. (2015). Handbook of Life Design: From Practice to Theory and from Theory to Practice. Firenze: Hogrefe.

Oral, T., & Gunlu, A. (2021). Adaptation of the Social Distancing Scale in the Covid-19 Era: Its Association with Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Resilience in Turkey. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1-18. doi. 10.1007/s11469-020-00447-1

Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Idoiaga Mondragon, N., Dosil Santamaría, M., & Picaza Gorrotxategi, M. (2020). Psychological symptoms during the two stages of lockdown in response to the COVID-19 outbreak: an investigation in a sample of citizens in Northern Spain. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 1491. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01491

Park, C. L. (2010). Making sense of the meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological bulletin, 136(2), 257. doi: 10.1037/a0018301

Presti, G., McHugh, L., Gloster, A., Karekla, M., & Hayes, S. C. (2020). The dynamics of fear at the time of COVID-19: A contextual behavioral science perspective. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 17(2), 65-71. doi: 10.36131/CN20200206

QSR International. (2014). NVivo 11 for Windows Help. Retrieved May 18, 2021, from http://help-nv11.qsrinternational.com/desktop/welcome/welcome.htm

QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018) NVivo (Version 12). Retrieved June 15, 2021, from https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

Rogowska, A. M., Kuśnierz, C., & Bokszczanin, A. (2020). Examining anxiety, life satisfaction, general health, stress and coping styles during COVID-19 pandemic in Polish sample of universitystudents. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 797-811.doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S266511

Santisi, G., Lodi, E., Magnano, P., Zarbo, R., & Zammitti, A. (2020). Relationship between psychological capital and quality of life: The role of courage. Sustainability, 12(13), 5238. doi: 10.3390/su12135238

Savickas, M. L. (2003). Toward a taxonomy of human strengths: Career counseling’s contribution to positive psychology. In W. B. Walsh (Ed.), Counseling psychology and optimal human functioning (pp. 229-249). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Scheier, M. F., & Bridges, M. W. (1995). Person variables and health: Personality predispositions and acute psychological states as shared determinants for disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 57, 255-268.

Schimmenti, A., Billieux, J., Starcevic, V. (2020). The four horsemen of fear: An integrated model of understanding fear experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 17, 41-5. doi: 10.36131/CN20200202

Schimmenti, A., Starcevic, V., Giardina, A., Khazaal, Y., & Billieux, J. (2020). Multidimensional assessment of COVID-19-related fears (MAC-RF): A theory-based instrument for the assessment of clinically relevant fears during pandemics. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 748. doi. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00748

Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48(6), 1273-1296. doi: 10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

Vargo, D., Zhu, L., Benwell, B., & Yan, Z. (2021). Digital technology use during COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid review. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(1), 13-24. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.242

Wang, G., Zhang, Y., Zhao, J., Zhang, J., and Jiang, F. (2020). Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet, 395, 945-947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X

Watson, S. F. (2003). Courage and caring: Step up to your next level of nursing excellence. Patient Care Management, 19, 4-6.

Zammitti A., Zarbo, R., & Magnano, P. (2018). Rete e tecnologia per le pratiche di orientamento: un percorso online per il potenziamento della Risk Intelligence. Newsletter n. 3. Retrieved from https://www.sio-online.it/

1 Psicologo, Esperto in Job Placement, Dottorando di ricerca, Dipartimento di Scienze della Formazione, Università di Catania.

2 Psicologa, Dottoranda di ricerca, Facoltà di Scienze dell’Uomo e della Società, Università Kore di Enna.

3 Professore ordinario di Psicologia del Lavoro e delle Organizzazioni, Dipartimento di Scienze della Formazione, Università di Catania.

4 Professoressa associata di Psicologia Sociale, Facoltà di Scienze dell’Uomo e della Società, Università Kore di Enna.

5 Psychologist, Job placement expert, PhD Student, Department of Science of Education, University of Catania.

6 Psychologist, PhD Student, Faculty of Human and Social Sciences, Kore University of Enna.

7 Full professor of Work and Organizational Psychology, Department of Science of Education, University of Catania.

8 Associate Professor of Social Psychology, Faculty of Human and Social Sciences, Kore University of Enna.

Vol. 14, Issue 2, June 2021